Lessons from Super Typhoon Ida: Disastrous Flooding Spurs Modern Mitigation in Japan

Sep 20, 2018

Editor's Note: This year marks the 60th anniversary of Super Typhoon Ida. Although Japan is subject to frequent typhoons, Ida’s heavy rains around the country’s capital caused unprecedented flooding damage. This article examines the aspects of weather and civil planning that combined in this disaster.

Sixty years ago, on September 26, 1958, Super Typhoon Ida struck Japan’s Kanagawa Prefecture on the island of Honshu. While there was some wind damage, the vast majority of Ida’s damage was caused by the deluge of rain from the Izu Peninsula to the capital city of Tokyo and beyond (see Figure 1), which led to flooding and mudslides. AIR estimates if Ida were to recur today, it would result in insured losses of approximately JPY 2.86 trillion (USD 25.2 billion).1

Typhoon Ida remains one of the country’s most devastating precipitation-induced flood disasters. This article examines why, on an island that frequently experiences typhoons, this storm caused such significant damage, and how companies can prepare for a similar recurrence today.

Intense Storm Brings Record Rainfall

Super Typhoon Ida formed in the west central Pacific Ocean on September 20, 1958, as a tropical depression. Ida rapidly blew up to a typhoon of record-breaking intensity with a central pressure of 877 mb and winds in excess of 320 km/h. By the time it made landfall in Kanagawa Prefecture on September 26, it was less intense, but still had wind speeds the equivalent of a Category 3 hurricane, up to 118 mph, that damaged more than 4,000 buildings, primarily in cities along the coast such as Chubu, Kanto, and as far north as Tohoku. Ida’s rains, however, were the real danger.

One week earlier, Super Typhoon Helen had followed a similar path and drenched the same region. Helen’s precipitation-induced flooding inundated nearly 50,000 homes after it made landfall on September 17. The saturated soil had little time to recover before Ida hit, exacerbating the flood risk.

Super Typhoon Ida produced the most intense rainfall that region had experienced in 60 years, with up to 400 mm of precipitation over two days. As the storm made landfall, rainfall rates approached 76 mm per hour in some areas, flooding waterways and triggering more than 1,900 mudslides. Two villages on the Izu Peninsula were completely washed away. Ida’s heavy rains caused an unprecedented loss of property across Tokyo and environs. A record-breaking number of houses—most of them new—were damaged by floodwaters, leaving more than 500,000 people homeless and 1,200 dead.

Boomtowns and Increasing Vulnerability

To get an idea of why Ida’s impact was so strong, we can look to the urban expansion at the time. After 1945, a period of record economic growth began, which eventually became known as the “Japanese economic miracle.” The rise of manufacturing and other jobs in Tokyo brought an influx of population to the region.2 With increasing prosperity came a rise in property prices and a housing boom; many of the new houses were built on less expensive but flood-prone lands in the suburbs.3

Because roughly 80% of Japan is mountainous, the utilization of floodplains for development is inevitable. But as late as the 1940s, a significant percentage of the land around Tokyo’s rivers was still forest or field—naturally occurring flood defenses that absorbed water back into the soil.4 During rapid growth, much more of this land was paved, with urbanization rates rising to 75% by 1955.5 Japan's rivers are short and steep, prone to reach peak discharge quickly after the start of rainfall. The increased land impermeability shortened the time to peak discharge further, which increased peak river volume. This set the stage for larger, more rapid floods on lands now populated with homes.

Flash Floods and Aging Levees

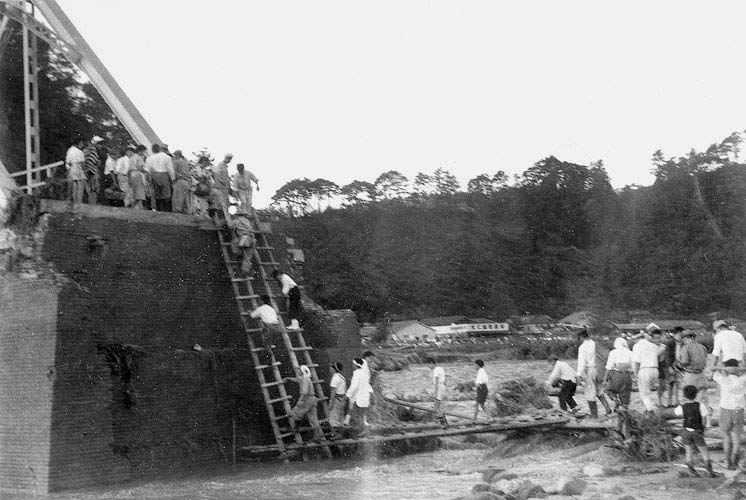

Ida’s rains drenched the region during the course of two days, causing several rivers east of Tokyo to burst their banks and flood the suburbs there (see Figure 2). Some of the worst destruction and loss of life, however, was along waterways in the western suburbs. Ida’s heaviest rains fell west of Tokyo, inundating the headwaters in the mountains and river valleys, triggering flooding and mudslides.

The area of the Izu Peninsula around the Kano River (Kanogawa) experienced some of the highest rainfall rates. Bridges over the Kano clogged with debris, forming temporary dams that, when they broke, caused flash floods that undercut riverbanks and destroyed levees not built to withstand such an onrush of water. In Japan, the storm was named Kanogawa Typhoon after the devastation in this area.

Japan’s first River Law, passed in 1896, required levees to be constructed along riverbanks and meandering channels to be straightened so that water would flow directly out to sea and not apply undue lateral forces to them.6 While a new Kanogawa drainage channel project had been started before 1958, it had not been completed when Ida struck. In the aftermath of Ida’s destruction, municipal planners expanded the width of the waterway and the number of tunnels before the project was completed in July 1965.

Modern Flood Mitigation

Ida preceded Typhoon Vera—the costliest weather-related disaster in Japan's recorded history—by only one year. Because of the destruction caused by these and earlier typhoons, the government undertook a massive effort to strengthen coastal and inland flood defenses throughout Japan. Ida in particular was the starting point of comprehensive plans to improve river flood measures for Greater Tokyo.7 Most major cities are now protected by sophisticated systems that safely redirect floodwaters from Japan’s frequent typhoons and other storms.

Approximately 75% of total insurable property is located on Japan’s floodplains, and with the ongoing issue of increasing urbanization, Japan continues to invest heavily in civil planning and engineering flood mitigation measures. The Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel—the world's largest underground floodwater diversion facility—was completed in the Greater Tokyo Area in 2006, and is a popular tourist destination. Less well-known is the impressive series of tunnels that make up the Ring Road No. 7 Underground Regulating Reservoir. Buried beneath one of Tokyo’s major thoroughfares, this facility’s capacity of approximately 540,000 cubic meters protects present-day Tokyo from the overflow of one river—the Kando—and by 2026, it will be connected to a series of other reservoirs, creating a multi-basin facility with a floodwater storage capacity of around 1,430,000 cubic meters across five rivers.8

Managing Japan Typhoon Risk and Building Resilience

To prepare for disasters such as Typhoon Ida, one must understand the range of possible losses—before they occur.

The AIR Typhoon Model for Japan shows how accurately Ida’s precipitation-induced flood hazard can now be modeled, including the impact to property at the time of the event and how that impact could be mitigated were Typhoon Ida to recur. Ida, however, is just one example of the extensive and widespread damage typhoons can produce in Japan and around Tokyo. The model realistically simulates the full range of precipitation patterns associated with typhoons. AIR’s model uses an innovative approach to capture precipitation from all sources for a more realistic view of antecedent conditions; a two-dimensional flow model to more accurately simulate flood depth; and an updated industry exposure database that reflects properties at risk. The AIR model also explicitly accounts for the designed capacity of flood defenses—including levees—as well as their current state of repair, which can differ notably from design conditions, and explicitly accounts for updated mitigation efforts in Japan, including the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel and the Ring Road No. 7 project.

Ultimately, catastrophe models—such as the AIR Typhoon Model for Japan—help organizations evaluate the full range of potential events so that they can manage the risk effectively; understand how those events will impact them; and mitigate losses and enhance resilience through planning and engineering.

References

1 All USD amounts are based on an exchange rate of JPY 1 = USD 0.0090, current as of the end of July 2018.

2 Vintage GIS: population growth and Vintage GIS: urban manufacturing.

3 Characteristics of the Flood Damage caused by the Kanogawa Typhoon in the western Suburbs of Tokyo

4 Shielding Tokyo from a Changing Climate

5 Tokyo Metropolitan Government, River Projects in Tokyo

6 Historical assessment of Chinese and Japanese flood management policies and implications for managing future floods

7 Tokyo Metropolitan Government, River Projects in Tokyo

8 Shielding Tokyo from a Changing Climate

Marc Marcella, Ph.D.

Marc Marcella, Ph.D. Ruilong Li, Ph.D.

Ruilong Li, Ph.D.