North Carolina had an extremely wet February in 2021 and experienced widespread flooding as a result. It was the state’s 17th-wettest February since 1895 according to the National Centers for Environmental Information. Flooding occurred particularly in eastern parts of the state along the Cape Fear, Neuse, Tar, Roanoke, and Lumber rivers. And on February 21 the National Weather Service warned of major flooding on the Little Pee Dee River at Galivants Ferry, the Waccamaw River at Conway, and the Lumber River at Lumberton.

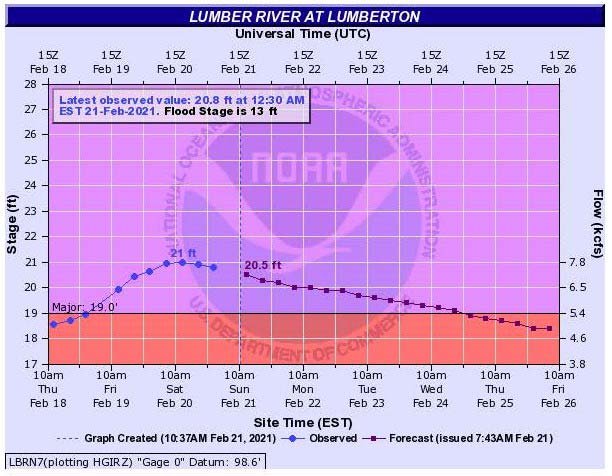

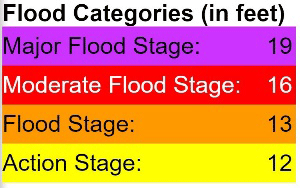

The Lumber, which flows through a flat coastal plain in south-central North Carolina, has been designated as a National Wild and Scenic River. As well as being one of the most highly prized recreation sites in the state it can also, unfortunately, be a source of flooding. In late February 2021 the river crested just above 20.4 feet—the third time since 2016 it has crested above 19 feet, the level that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) considers “major flood stage.”

At this stage of flooding the river and nearby Cox Pond merge. To the east, the only visible parts of Noir Street are the signs at the intersections in the flooded neighborhood. Mercifully it wasn’t as bad as the 28-foot crest from Hurricane Matthew in 2016 or the 29-foot crest from Hurricane Florence in 2018. Those events laid bare the risks of living and working so close to a river that once brought prosperity to the city but now threatens to take it away. Flood risk has disproportionately impacted Lumberton’s economy and residents.

Lumberton, surrounded by cotton fields, is the only city in otherwise rural Robeson County. These fields provided the raw materials and attracted the manufacturers that established factories there and drove Lumberton’s economy in the 20th century—Alamac American Knits, Kayser-Roth, and Georgia-Pacific.

Factory workers settled nearby, with many of them occupying low-lying areas to the south of the river. A levee was built in the 1970s by the state to protect a portion of this area, but it was never certified by FEMA to protect against a 1% annual occurrence flood. Major floods in the area were not experienced for more than 30 years; even flooding from Hurricane Floyd crested at barely 20 feet in 1999. Flood insurance uptake remained low, with fewer than 10% of structures in the two census tracts south of the river having flood insurance.

Hurricane Matthew

Communities on the south side of the Lumber River were shattered by Hurricane Matthew. The river crested at 28 feet, the highest crest on record by 8 feet. When the river’s level reaches about 22 feet, water starts to pour through the levee where the railroad tracks pass through it. As the level rose above this point water poured through, inundating hundreds of structures. The brand-new Walmart sustained more than USD 1 million in damage to its building and stock, and its closure for several months forced customers to travel farther for their essential purchases.

The Georgia-Pacific and Alamac plants were physically undamaged by the floodwaters because their builders had constructed them on concrete slabs that were higher than the 1% annual water level. The roads that connected the plants to the rest of the world, however, were impassible for weeks, idling their production lines and workers. This proved to be the downfall of Alamac. The company was unable either to fulfill customer orders or to file a claim for business interruption due to flooding; it foundered after the major brands canceled their contracts. The plant closed in 2017 and laid off the final 157 workers; more than 500 had been employed there before Matthew struck.

Hurricane Florence

Two years later, Hurricane Florence brought yet more severe flooding to Lumberton. Still greater quantities of water poured in from the railroad underpass through the levee, and even more homes and businesses were flooded, some of which had just finished rebuilding after Matthew. Fortunately, the lessons from Matthew had not gone unheeded by residents; flood insurance uptake had increased to more than 25% in the areas south of the Lumber River, helping to blunt the financial strain of recovery. Walmart had learned its lesson too, trucking in a huge inflatable dam that kept the floodwaters at bay. This time the only losses were USD 20,000-worth of refrigerated products, which spoiled when power was lost.

Resilience Is Multi-Faceted

The difference in outcomes in Lumberton between Matthew and Florence shows that the NFIP can help build resilience against flooding in communities to a certain degree, but in isolation it’s not enough to ensure it.

The rate of decrease in the number of occupied housing units was less after Hurricane Florence than it had been after Matthew, but it still demonstrates that the NFIP isn’t able to guarantee that people will be able to return to their homes after a flood. Alamac suffered no direct losses from flooding but closed due to loss of contracts caused by business interruption. So long as the railroad underpass through the levee is unsecured, so long as existing flood insurance coverage fails to meet the needs of policyholders, and so long as structures remain in high flood risk areas, the protection gap will hinder resilience in Lumberton.

Quantify flood risk and uncover new opportunities with AIR inland flood models