Perspectives

Severe Thunderstorms Happen All the Time, So Why Model Them?

August 22, 2011

With the memory of the most prolific and destructive U.S. tornado season on record fresh in our minds, and its impact on insurance balance sheets still unfolding, it's a good time to note that catastrophe modeling is essential not just for large-scale, highly infrequent events like earthquakes and hurricanes.

A commonly cited rationale for investment in catastrophe models is their ability to help us prepare for events whose scope exceeds historical experience—that is, for events that are so severe that they happen only very infrequently. Yet models can also add significant benefits, and expand our historical perspective, even for hazards that happen with a degree of regularity.

Let's look at three aspects of the case for modeling events that may happen somewhat frequently and over smaller regions, yet in aggregate cause severe financial impacts.

Frequent Hits Can Add Up to Large Losses

For extremely rare scenarios, the distinction is not significant between the potential loss from a single "knockout punch" event and the cumulative loss over a reporting or planning period, like a fiscal year. For example, the probability of two or more extremely severe earthquakes in a single year is so small that it does not drive the aggregate annual loss estimate. But the main financial threat to insurers is sometimes the accumulation of multiple hits to the bottom line in a single year.

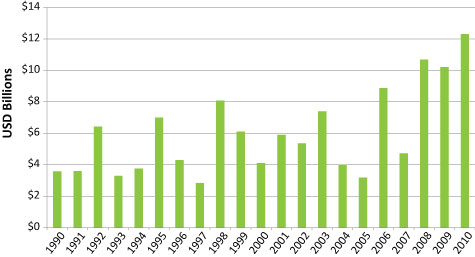

Some U.S. insurers have cited accumulated severe thunderstorm losses as the driver of recent poor results even prior to the 2011 spring storm season. One used Figure 1 below in its annual board of directors meeting. Just as with the hurricane and earthquake perils, the long-term trend in annual aggregate losses is upward. This is likely for the same demographic and economic reasons—a growing population is increasingly living and working in more expensive buildings and spreading out into harm's way.

Furthermore, traditional forms of risk-sharing, such as excess-of-loss reinsurance, are often designed primarily to ensure solvency in the year of the "knockout". They often give insufficient attention to protection against the loss of multiple retentions that together can weaken the balance sheet. As a result, the types of disasters that drive the stress scenarios net of reinsurance may be much different than those driving the gross losses.

Yet we see that many insurers heavily exposed to severe thunderstorms, and actively modeling hurricanes and earthquakes, make little or no investment in modeling the perils that contribute most to volatility in financial results. This is despite the fact that it is convenient to do so, from a workflow viewpoint: the options are right there in the same software platform.

Modeling severe thunderstorms in conjunction with other perils improves understanding of the annual and multi-year aggregate financial impact of all hazards. It also drives better design of risk-sharing and hedging strategies to protect against volatility in earnings and the capital base, ultimately supporting the market valuation of the insurer.

The Inadequacy of the Historical Data — Modeling Fills in the Gaps

Financial and enterprise risk management aside, the underwriting and actuarial executives have the problem of selecting and pricing risks at a much more granular level. Both geography and building attributes must be analyzed in detail. Rating elements often depend on the exact street address of the property as well as detailed construction features, such as the number of stories. These managers must "zoom in" to a level that almost guarantees insufficient data about historical events affecting any one area and type of risk.

Models fill in the gaps by simulating tens of thousands of events, generating a critical mass of data for actuarial analysis in even small zones. Using these results, different rates and underwriting practices for adjacent territories or progressively stronger construction may be more easily justified to producers and regulators. Models may also be set to operate on "hypothetical" data sets, such as samples of typical homes of various construction types in a given ZIP Code, to ensure that granular differences in expected losses are captured. The insurer thereby achieves a robust rating plan and a greater degree of confidence in the precision of regional rules and parameters.

Stress Testing the "What-If"s

With the additional information generated by models, it is easy to test the sensitivity of financial outcomes to new knowledge or decisions being contemplated. A company's perception of risk might shift when it develops insight from testing issues such as:

- What if construction types reported as "unknown" in the data were assumed to be the weakest available materials? Stronger materials?

- What if each modeled event produced 20% more losses than anticipated by the original model run, perhaps due to underinsurance (insured values differing from actual replacement values) or other valuation difficulties?

- What if an exposure management program resulted in retraction of 10% in one region and growth of 10% in another in the same state? What would be the impact on expected annual catastrophic losses and the severe scenarios tested for ratings agencies?

Whether the expected frequency of the hazard is extremely low or merely occasional, it is simply not feasible to "massage" historical data to match the spectrum of investigation made possible by catastrophe models. Model-driven analysis leads to better decisions in many operational areas—in the examples above, from the choice of risk data requested on the insurance application, to the choice of replacement value estimates, to the targets of the growth strategy.

Models Don't Change Reality, but Can Help You Control Its Impact

No model will change what happens on the ground in a given year. Some types of hazards simply strike more frequently than others, and in sometimes unfortunate areas. But the financial impact of the physical outcomes is not a foregone conclusion; it depends on many decisions made prior to the zero hour about where to write policies, how much to charge, and how to protect the book of business from one or more disasters in a year.

To the informed investor or owner of an insurance enterprise, an excuse for missing an earnings or capital target of "these things just happen now and again" should not be credible. Catastrophe models extend the organization's ability to execute the classic strategies of risk management—avoidance, mitigation, and sharing—even when the risks are not unprecedented or too infrequent to observe. They should be deployed even when the hazard is relatively familiar, so that insurers are not at the mercy of unpredictable Mother Nature.