Perspectives

Building a Climate-Resilient Future: The Role of Insurance

December 2, 2019

In the past few years, there has been a marked shift in public opinion regarding climate change. The percentage of Americans that consider climate change a major threat to the well-being of the country has grown from 45% in 2013 to 57% in 2019, according to Pew Research Center surveys. Likewise, in the United Kingdom, 80% of respondents to a Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy survey indicated that they were “fairly concerned” or “very concerned” about climate change, up from 66% in 2013.

The increase in significant weather disasters, not only in vulnerable developing countries but also in wealthy ones, is one of the driving forces. In 2017, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria--all occurring within a month—generated nearly USD 270 billion in economic losses, and U.S. wildfires in 2017 and 2018 resulted in more than USD 40 billion in economic losses. This past August, Hurricane Dorian ravaged the Bahamas, tying the record for the strongest winds at landfall in the Atlantic. In the Pacific, Japan was struck in back-to-back seasons by Typhoon Jebi in 2018 and Typhoon Hagibis in 2019, which in total caused more than USD 20 billion in damage. And Mozambique was hit with Cyclone Idai, the worst natural disaster in the region in several decades, followed by Cyclone Kenneth just six weeks later. Historic, record-setting events are seemingly becoming the norm.

While no individual natural catastrophe can be directly attributed to climate change, globally increasing temperatures create conditions that are more conducive to a higher frequency or severity (or both) of a multitude of perils, including hurricanes, severe storms, floods, wildfires, and droughts. For example the recurrence of a rainfall event like Hurricane Harvey is estimated to have increased from 2,000 years in the late 1900s to 325 years today to a projected 100 years by the end of this century.

The long-term economic consequences are far-reaching, spanning the financial, housing and infrastructure, agriculture, and geopolitical security sectors, among others. In fact, many economists across the globe have identified climate change as one of the defining challenges of the 21st century, and the World Economic Forum in the Global Risks Report 2019 named extreme weather and failure of climate change adaptation as two of the top three risks in terms of possible impact. The (re)insurance industry is uniquely at risk. As payouts increase, so will the price of protection, raising the question: Is the future insurable? In other words, will insurers be able to offer protection that home- and business-owners can afford? Or will the industry be forced to withdraw, widening the protection gap? While not a near-term danger, it is no longer a far-fetched, alarmist contemplation that the future of insurance may be at stake.

The long-term economic consequences are far-reaching, spanning the financial, housing and infrastructure, agriculture, and geopolitical security sectors, among others. In fact, many economists across the globe have identified climate change as one of the defining challenges of the 21st century, and the World Economic Forum in the Global Risks Report 2019 named extreme weather and failure of climate change adaptation as two of the top three risks in terms of possible impact. The (re)insurance industry is uniquely at risk. As payouts increase, so will the price of protection, raising the question: Is the future insurable? In other words, will insurers be able to offer protection that home- and business-owners can afford? Or will the industry be forced to withdraw, widening the protection gap? While not a near-term danger, it is no longer a far-fetched, alarmist contemplation that the future of insurance may be at stake.

Fortunately, we know the (re)insurance industry to be adaptable and innovative. In this article, I uncover the root of the inertia surrounding climate change action, consider that the tides may finally be turning, and offer a roadmap for how catastrophe modelers and (re)insurers can work together to improve analytics, incentivize better building practices, and explore new risk transfer solutions to build a more climate-resilient future.

The Cost of Inaction

Despite shifting opinions, the prevailing response to the threat of climate change has largely been inaction. Residents and businesses continue building or rebuilding in disaster-prone areas that will become increasingly at risk from climate-related disasters, particularly on the coast, on floodplains, and in the wildland-urban interface—a region most at risk for wildfires. The reasons are a complex blend of politics, psychology, and of course, economics.

First, people tend to be short-sighted when thinking about adverse events with low probability. Even after a disaster occurs, interest in risk mitigation measures initially rises but then lessens and levels off to pre-disaster levels. For example, flood and earthquake insurance take-up rates typically spike after an event, but then gradually decrease as memory of the disaster fades and people weigh the perceived risk against the price of protection. Furthermore, future risk from climate change rarely figures into the decision to purchase a house.

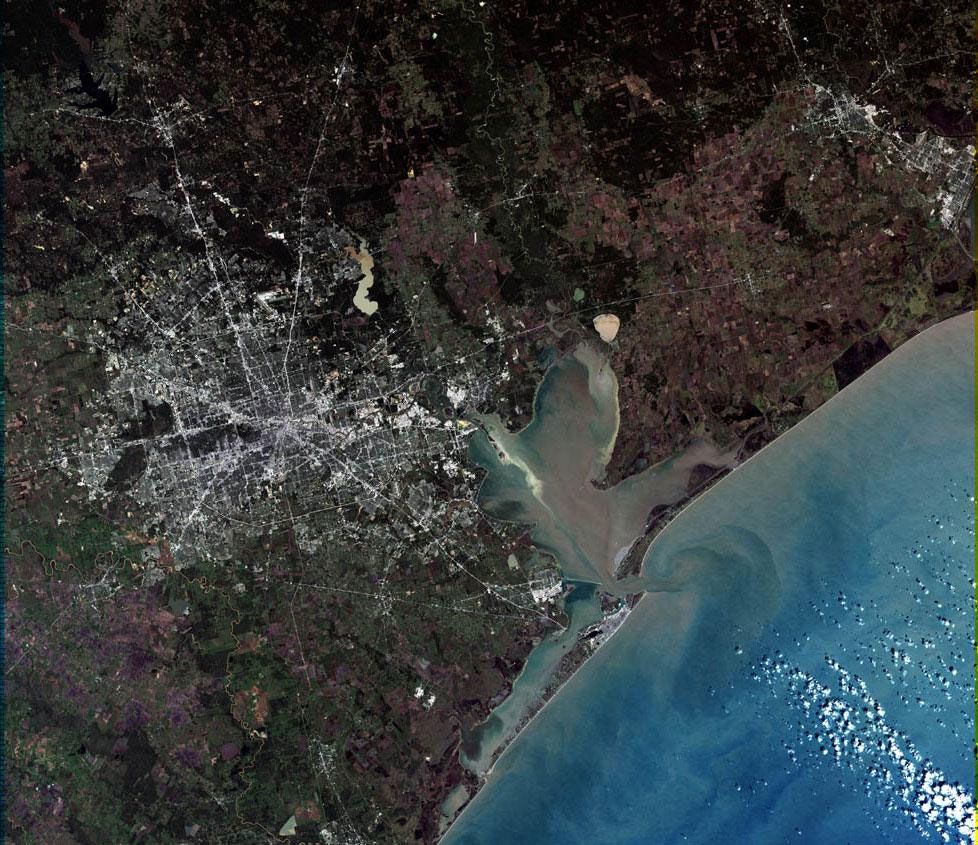

Second, risk information is inadequate. For example, while many people depend on FEMA flood maps to determine their risk of flooding, the purpose of the maps is to delineate the special hazard areas and the risk premium zones applicable to the community under the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). The maps are designed to facilitate the NFIP program, not to communicate flood risk more broadly. Unfortunately the maps can create the false impression that because a property is out of the special flood hazard area, the property is not at risk. For example, FEMA maps do not indicate areas at risk from off-floodplain flooding, which is a significant driver of loss; most of the homes flooded by Hurricane Harvey were not on the floodplain.

Second, risk information is inadequate. For example, while many people depend on FEMA flood maps to determine their risk of flooding, the purpose of the maps is to delineate the special hazard areas and the risk premium zones applicable to the community under the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). The maps are designed to facilitate the NFIP program, not to communicate flood risk more broadly. Unfortunately the maps can create the false impression that because a property is out of the special flood hazard area, the property is not at risk. For example, FEMA maps do not indicate areas at risk from off-floodplain flooding, which is a significant driver of loss; most of the homes flooded by Hurricane Harvey were not on the floodplain.

Finally, properties in high-risk areas are often the most in demand. In coastal states at risk from flooding, coastal construction can far outpace inland construction in some places because of the appeal of waterfront living; in other places, such as the Houston metro area, urban sprawl due to the lack of zoning laws drives construction in high-risk areas. Developers have clear incentives to continue building in desirable areas, with little regard to the fact that the property may be flooded many times over the course of a typical mortgage. Land use policies may not keep pace with risk information, and local governments may be hesitant to discourage the tax revenue. In the case of some high-risk areas, backstop insurance programs charge below-market rates, creating an incentive to continue development on ecologically fragile land, which, ironically, if left untouched would provide some of the best natural protection against many natural disasters.

So what is the potential cost of inaction? A recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that, on a global basis, economic losses would total USD 54 trillion by 2100 with a 1.5°C of warming of the planet, USD 69 trillion with 2°C of warming, and USD 551 trillion with 3.7°C of warming. Of course, only a portion of these estimates would be related to the property and casualty insurance market and there is enormous uncertainty associated with climate-related projections, but the magnitude of the problem is clear.

So what is the potential cost of inaction? A recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that, on a global basis, economic losses would total USD 54 trillion by 2100 with a 1.5°C of warming of the planet, USD 69 trillion with 2°C of warming, and USD 551 trillion with 3.7°C of warming. Of course, only a portion of these estimates would be related to the property and casualty insurance market and there is enormous uncertainty associated with climate-related projections, but the magnitude of the problem is clear.

Maintaining the status quo, responding to growing losses on a year-by-year basis by raising premiums is ultimately unsustainable in the long term. Insurers may attempt to limit payouts to keep rates affordable, which would reduce the attractiveness of insurance. Regulators may try to set maximum premiums, which can drive private insurers out of the market altogether, as was the case in Florida after the 2004/2005 hurricane seasons. Like the fable of the frog in boiling water, gradual changes may seem inconsequential until it’s too late. A growing protection gap forces the burden of disaster recovery onto taxpayers, and we have seen firsthand in recent years the enormous toll that catastrophes can take on underinsured economies such as Haiti and Nepal. Without expedient action from both the private insurance industry and government entities, climate change will reduce the availability and affordability of insurance throughout the globe, exacerbate the protection gap, and may even threaten the solvency of (re)insurance companies.

Changing Tides

(Re)insurance companies are increasing their focus on the risks posed by climate change, and here at AIR, we are hearing more concern from our clients than ever before. They are beginning to look beyond the upcoming year to a time horizon of at least 10 to 15 years, and some are divesting their investment portfolios of fossil fuel companies (a few have even stopped underwriting these companies).

Governments and regulators are also improving efforts to examine climate resilience. This year, the Governor of Florida appointed the state’s first chief resilience officer, the California Insurance Commissioner appointed the first Deputy Commissioner for Climate and Sustainability, and the Washington Insurance Commissioner hired a Senior Climate policy Advisor. Also, for the first time this year, the Prudential Regulatory Authority at the Bank of England is requesting that large insurance firms quantify the impact of several climate change scenarios on potential losses as part of the General Insurance Stress Test; other regulators are expected to follow suit. For publicly traded (re)insurers, the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is also spurring action.

Governments and regulators are also improving efforts to examine climate resilience. This year, the Governor of Florida appointed the state’s first chief resilience officer, the California Insurance Commissioner appointed the first Deputy Commissioner for Climate and Sustainability, and the Washington Insurance Commissioner hired a Senior Climate policy Advisor. Also, for the first time this year, the Prudential Regulatory Authority at the Bank of England is requesting that large insurance firms quantify the impact of several climate change scenarios on potential losses as part of the General Insurance Stress Test; other regulators are expected to follow suit. For publicly traded (re)insurers, the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is also spurring action.

As with most forms of extreme event risk, it is impossible to predict the exact timing, magnitude, and cost of the next catastrophe. Climate risk is even more uncertain in that historical data has limited utility in assessing future risk. However, unlike black swan events that are completely unexpected and unfathomable, climate risk is more of a “known unknown.” We may not have a full picture of the potential environmental, economic, and human impact, but we have some sense of the magnitude of the problem, and political interests and public opinion may finally be aligning with financial incentives to spur meaningful climate action for the (re)insurance industry.

What Can We Do?

Beyond ensuring future solvency, I believe that the (re)insurance industry has a pivotal role to play in building climate resilience. AIR collaborates with industry partners and trade and research organizations to improve risk awareness and share what we know about the potential impact of climate on extreme events (projected impacts summarized in the figure below). Despite the uncertainties, we believe that high-quality analytics can empower (re)insurers to make risk-informed and financially sound decisions, and that the insurance industry is in a unique position to incentivize risk reduction and improve building practices to improve future resilience. There is also a pressing need to help municipal, state, and federal governments understand how climate risks will impact communities, which will help guide their policymaking, risk reduction, and disaster financing; this is one of the main objectives of AIR’s Global Resilience Practice. The next sections describe some of the areas we are focusing on as we continue our commitment to helping our clients manage climate risk.

Pricing Risk

A crucial factor in understanding and managing climate risk is making sure that current risk is properly priced. Modeling tools traditionally use the best available historical data to simulate potential events. With climate change, however, past data may be associated with significantly different climate conditions that no longer reflect current risk. To create a forward-looking view of risk, a model provider may choose to limit the historical data used in model development to better represent the current climate, although doing so may reduce the natural variability in the range of modeled events. We carefully weigh these and other considerations during model development to ensure that our models reflect today’s climate, and we are working on improved documentation to help our clients understand the associated limitations and uncertainties. With input from our clients, we are exploring a number of ways to provide alternative views of risk.

For an individual property, proper risk pricing means knowing its exact location and the physical attributes that affect its vulnerability to different perils. The importance of detailed and accurate exposure data cannot be overstated and is one reason we are constantly working on improving our geocoding and data quality capabilities, as well as pushing our clients to improve data collection practices. High-quality exposure data, including secondary risk characteristics, enables granular risk differentiation, which ultimately gives policyholders a truer sense of their risk and reduces the prevalence of lower risk policies subsidizing higher risk ones. This would decrease the attractiveness of more disaster-prone properties and incentivize policyholders to reduce risk, especially in the face of increasing losses from perils such as flood and storm surge.

For an individual property, proper risk pricing means knowing its exact location and the physical attributes that affect its vulnerability to different perils. The importance of detailed and accurate exposure data cannot be overstated and is one reason we are constantly working on improving our geocoding and data quality capabilities, as well as pushing our clients to improve data collection practices. High-quality exposure data, including secondary risk characteristics, enables granular risk differentiation, which ultimately gives policyholders a truer sense of their risk and reduces the prevalence of lower risk policies subsidizing higher risk ones. This would decrease the attractiveness of more disaster-prone properties and incentivize policyholders to reduce risk, especially in the face of increasing losses from perils such as flood and storm surge.

Creating Incentives and Risk Mitigation Strategies

The (re)insurance industry can build resilience in at-risk communities by improving the use of analytics to assess different mitigation strategies. Investment in strengthening properties is proven to reduce disaster losses, benefiting both property owners and insurers. However, developing a comprehensive and actuarially sound mitigation credit program can be challenging, requiring modeling tools that can assess how the impact of different mitigation features varies with geography and year of construction, both in isolation and in combination with other features. Mitigation credits in the U.S. are most commonly used to reduce wind losses, but discounts are available for seismic and flood retrofitting as well. Insurers have also begun offering discounts for wildfire mitigation efforts, including using fire-resistant materials and increasing defensible space around the home, and for community-wide wildfire resilience efforts. Further efforts can be expanded by working with municipalities to structure loans to property owners to improve physical resilience.

At the community level, AIR’s Global Resilience Practice works with municipal governments to quantify the potential climate-related losses and assess the effectiveness of physical mitigation strategies, infrastructure improvements, and financial instruments. The AIR team has been working with coastal cities to understand the impact of sea level rise on flood losses and to make a business case for resilience investments.

At the community level, AIR’s Global Resilience Practice works with municipal governments to quantify the potential climate-related losses and assess the effectiveness of physical mitigation strategies, infrastructure improvements, and financial instruments. The AIR team has been working with coastal cities to understand the impact of sea level rise on flood losses and to make a business case for resilience investments.

Designing Risk Transfer Mechanisms

Another concrete action that the insurance industry can take to improve climate resilience is through community insurance and microinsurance products; data and analytics play a significant role here as well. In the public sector, World Bank initiatives such as the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative and the Pacific Alliance earthquake bonds use AIR models to design parametric insurance protection that pay out quickly in the aftermath of a disaster.

We are seeing similar initiatives on a smaller scale as well. Food production, for example, is highly exposed to climate risks, and insurers are exploring the use of parametric insurance to protect vulnerable farmers routinely exposed to drought and flood in Africa, Southeast Asia, and other regions. Such efforts need to be expanded in the face of climate change, and we at AIR are committed to continuing to improve our risk assessment capabilities beyond the markets traditionally served by insurance.

Another crucial strategy in building resilience and closing the global protection gap is to transfer risk to capital markets. Catastrophe bonds can provide governments with long-term protection where traditional markets fall short, providing disaster relief without additionally burdening taxpayers. A new type of catastrophe bond that is being conceptualized, called a resilience bond, is taking this idea even further by incentivizing municipalities to make infrastructure resilience improvements. The Coalition for Climate Resilient Investment, which was launched recently at the United Nations Climate Action Summit, is aimed at facilitating proper pricing of climate risk with regards to resilience bonds and other climate resilience initiatives.

Another crucial strategy in building resilience and closing the global protection gap is to transfer risk to capital markets. Catastrophe bonds can provide governments with long-term protection where traditional markets fall short, providing disaster relief without additionally burdening taxpayers. A new type of catastrophe bond that is being conceptualized, called a resilience bond, is taking this idea even further by incentivizing municipalities to make infrastructure resilience improvements. The Coalition for Climate Resilient Investment, which was launched recently at the United Nations Climate Action Summit, is aimed at facilitating proper pricing of climate risk with regards to resilience bonds and other climate resilience initiatives.

Closing Thoughts

As an industry whose core business is managing risk, (re)insurers are uniquely positioned to be able to create forward-thinking incentives and innovative products that can go a long way toward mitigating climate risk. For homeowners and business owners, insurers have the ability to significantly influence risk-reducing behaviors. For local, state, and federal governments, (re)insurers can play a key role in developing cost-effective strategies to increase insurance penetration, improve financial protection in the aftermath of an event, and most importantly, invest in proactive initiatives that will reduce future climate-related losses. Public-private partnerships are a key element to designing better mitigation strategies, mobilizing funds, communicating risk, and moving people out of harm’s way.

For our part, we at AIR understand the crucial role that data and technology plays in climate risk mitigation. Central to all of the recommendations I’ve put forth here is the ability to accurately assess and price the risk. While all of our models are forward-looking by design, climate change adds uncertainty; we are committed to collaborating with our clients to develop better ways of managing and reducing this uncertainty and to design better solutions for the future. I expect this to be an ongoing discussion for many years to come, and I am hopeful that we as an industry can see climate action as both a responsibility and an opportunity.