Fire Down Under: The Black Saturday Fires

Apr 16, 2009

April 16, 2009

Editor's Note: On Saturday, February 7, major bushfires broke out across the southeastern Australian state of Victoria. Known as the Black Saturday fires, the disaster was the deadliest fire in Australia's history and one of the country's most costly natural disasters of any kind. Weeks later, while pockets were still smoldering, AIR undertook a post-disaster survey of some of the hardest-hit areas north of Melbourne. In this article Dr. Praveen Sandri, Managing Director of AIR's Hyderabad office, reports on the February fires and the findings of AIR's survey1 . AIR Senior Research Scientist Dr. Tomas Girnius adds some background on the history of bushfires in Australia and on the nature of the peril today.

At the end of January and continuing into February of 2009, southeastern Australia was hit by an unprecedented heat wave. Already suffering from a decade-long drought, the region additionally had received no rainfall at all for more than a month. Conditions were so volatile that on Wednesday, February 5th, Victoria state fire and police officials held a joint media conference to warn the public of the danger of bushfires breaking out. On Saturday, February 7th, temperatures in Melbourne, the capital of Victoria, rose above 46°C (115°F). It was the highest temperature ever recorded in the city since record-keeping officially began in 1859.

That morning a fire was reported about 65 km (40 mi) north of Melbourne. It was the first of six major fires that began that day alone. Propelled by wind speeds gusting to more than 95 km/h (59 mph), the fires raced across the parched region. Within a few days 210 people had been killed, 500 injured, and nearly 8,000 left homeless. More than 2,000 homes were destroyed—among some 3,500 structures destroyed in all. More than 4,400 km2 (1,700 sq miles) of land was burned. Current estimates suggest insured losses of between AUD 1.0 billion and 1.5 billion.

The Victoria Bushfires of 2009

The "Black Saturday" fires were the deadliest natural disaster to strike Australia in over a century. The first of the fires reported that day was called in from the small town of Kilmore East. The fire quickly erupted into a massive blaze and spread to the south and east in the direction of the nearby towns of Wandong, Kinglake West, Kinglake Central, and Kinglake. Another fire, the Murrindindi Mill Fire (which is still being investigated for having a suspicious origin) was reported three hours later near a closed sawmill about 50 km (31 mi) east of Kilmore. It then spread south and east, toward the town of Marysville about 16 km (10 mi) away.

That night the two fires merged, creating a front that stretched for 80 km (50 mi) and became known as the Kinglake Complex Fire. More than 500 firefighters were engaged along the arc of the front, assisted by 33 tankers, a helicopter, and two fixed-wing aircraft. This was the most deadly and largest of the 23 fires fought that night and of the 40-some fires fought over the next days. The destruction wrought by the other fires on Black Saturday notwithstanding, ninety percent of the fatalities were caused by the Kinglake Complex Fire.

According to survivors, the fire sounded like a freight train as it roared into Kinglake. Its flames reached heights of 18 to 20 meters (60 to 70 feet). Tree tops burst into flame, home fuel tanks exploded, and quickly fire was everywhere.

Situated at the heart of the Kinglake Complex Fire on the night of February 9th was the town of Marysville. Many residents fled to the town's cricket field, which was one of several "designated refuge centers." Eventually, they numbered about 200, nearly half the town. A Fire Brigade Strike Team, its retreat from Marysville cut off by the surrounding inferno, also came to the field. Through the night, trees just beyond the field's perimeter exploded into balls of fire. When flames reached the fire trucks that had encircled the townspeople wagon-train fashion, the firefighters turned on their hoses. They had one water tanker, which held only 650 gallons.

Miraculously, all those on the cricket field survived. However, hardly a building was left standing. Marysville was decimated: at least 45 people were killed, almost one-tenth the town's entire population.

AIR Damage Survey

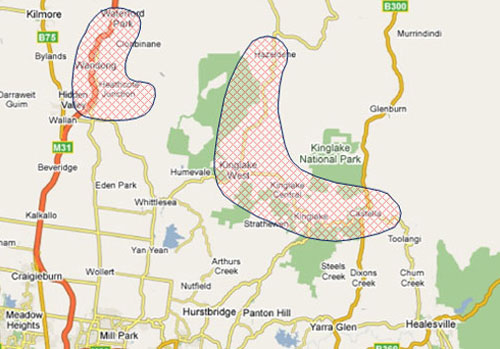

One month after the first of the fires ignited—even as some fires, although contained, still burned—AIR surveyed areas in and around the town of Kinglake, about 50 km (30 mi) northeast of Melbourne. (Marysville and its immediate surroundings were being treated as a crime scene and access to it was closed.) The region surveyed was generally rural and sparsely populated, yet within a 16 km radius (10 mi) of Kinglake at least 130 people were killed in the Black Saturday fires.

The survey area (shaded regions in Figure 1) is generally hilly and the roads often wind through forest, following the contours of the terrain. The trees are mostly eucalyptus and pine, species with high resin content. And they are tall—generally reaching at least twice the height of most buildings—with branchless trunks leading to full, leafy crowns. Between the trees grow grasses and other underbrush, though at the time of the survey, all that remained was a gray ash.

The purpose of the survey was to gather information on terrain, vegetation, building types and practices, and damage patterns in a typical bushfire-prone area. The photos below illustrate some of the salient findings of the survey.

Roads and other open spaces can act as firebreaks, but they were not effective in stopping the high speed Kinglake Complex Fire, as seen here in Figure 2 along the Main Mountain Road looking north toward Clonbinane. Propelled by winds of 100 km/h (60 mph), firebrands, embers and 10-meter (30 feet) high flames vaulted many barriers.

Commercial structures, like this store with its masonry walls and corrugated sheet metal roof, were destroyed as readily as private homes. Roofs of both residential and commercial construction were either of sheet metal, as here, or clay tiles.

Some residents stayed to defend their homes—a risky decision. The house shown in Figure 4—unusual in having two stories—suffered only minor roof damage to the lower extension. The owners said that embers did enter the house and started a fire in one room, but was quickly doused. Had the residents not stayed, the entire building would likely have been destroyed. Other residents who made the decision to stay and battle the flames were not so lucky.

As has been observed in virtually all of AIR's fire damage surveys, damage was almost always all or nothing (Figure 5). Very few structures showed only partial damage.

Buildings constructed with brick walls, as on the left in Figure 6, effectively suffered the same as buildings constructed of wood and/or masonry veneer, although the walls in most cases remained standing. For wood frame construction, chimneys are typically the only element still standing.

Not uncommon was the situation documented in Figure 7: the house on the left is virtually undamaged, while its neighbor a few meters away (note the time stamp) is completely destroyed. This damage pattern, captured by the AIR Wildfire Model for the U.S., has been repeatedly observed in each of AIR's damage surveys and can often be the result of a single airborne ember.

Bushfire Risk in Australia

The Black Saturday fires were only the most recent in a long history of similarly devastating fires. There have been Black Sunday, Red Tuesday, Black Thursday, Black Friday and Ash Wednesday fires. Until this February's fires, the Ash Wednesday fires of 1983 had been the most deadly. Igniting, not without irony, on Ash Wednesday of that year's Christian calendar, the fires killed 75 people. Winds gusted to over 112 km/h (70 mph) producing tornado-like fire whirls, fireballs three meters (10 ft) across, and temperatures—estimated afterwards from melted metals—of 2000°C.

The largest bushfire remains the Black Thursday fires, which began on February 6th of 1851. In a matter of days they burned through nearly a quarter of Victoria state. At roughly 52,000 km2 (20,000 square miles), the burnt area was about ten times larger than that of either Ash Wednesday or Black Saturday. In an era of sparse population, however, just 12 people were killed—but thousands of cattle and an estimated one million sheep perished.

Bushfires are part of the ecology that characterizes the continent. Most of Australia's interior is desert or semi-arid land that is also relatively flat. Given the continent's geographic proximity to the equator, its climate is generally warm. Temperatures commonly rise to over 38°C (100°F) and the air holds very little water. Vegetation quickly dries out—and burns easily.

Eucalypts, which today make up roughly 70% of the Australian forest and include the widely-known eucalyptus tree, evolved through millions of years of such conditions. Rich in highly flammable resins, having branches and bark that readily strip or shed and quickly accumulate, eucalypts are fuel waiting for a spark. They also, however, have evolved features that enable them to tolerate and even thrive with fire.

These environmental conditions are additionally affected and shaped by the La Niña-El Niño cycle that spans the Pacific Ocean. La Niña generally brings wet weather to Australia. During El Niño years, the opposite happens: high-pressure air masses develop over the Australian north and create persistent warm and dry conditions. They also set the conditions that drive the winds out of the hot, dry interior to blow across the southeast.

These climatic systems leave Australia—already the world's driest inhabited continent—with a highly variable rainfall climate. The Australian government's Bureau of Meteorology describes the country's rainfall experience as having about three good years and three bad years out of ten. Usually the "bad" period is broken by the return of La Niña, but this has not happened in recent years and the continent has had unusually low rainfall for the last decade. One recent study attributes this phenomenon to unprecedented warming in the Indian Ocean, which dictates the strength of the moisture-bearing winds that travel to Australia—and in recent years those winds have been weak. Consistent with this interpretation, perhaps, is an official "Drought Statement" issued by the Bureau of Meteorology on April 6th, which stated that the record heat and widespread drought southern and eastern Australia currently are experiencing "is without historical precedent and is, at least partly, a result of climate change."

These factors—together with increased population, increased construction in the "ildland-Urban Interface," and increasing water-intensive agriculture (that concentrates diminishing water supplies to certain areas, leaving others drier)—combine to increase the risk of fires. On average every year Victoria state experiences about 600 bushfires. Only about 25% are caused by natural events, chiefly lightning. An almost equal number are deliberately set: arson. The rest are attributable to one or another kind of human-associated activity or accident: campfires, sparks or exhausts from machinery, fallen utility lines, etc. As one academic has described it, Australian bushfires are caused by "lightning, the clumsies and the crazies." When conditions come together as they did on February 7th—long drought, no rain, very high temperatures, and strong and steady winds—catastrophe is bound to strike.

Editor's Note: AIR is currently developing a bushfire model for Australia.

1 AIR wishes to extend a warm thanks to Mr. Walter Reinhardt of the Great Barrier Reef Foundation for his acting as AIR's guide during the survey.