Will 2022 Be Another Above-Average Atlantic Hurricane Season?

Jun 14, 2022

For the second year in a row and the third time in history, the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season used all 21 names allocated by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) for the season. Along with the record-setting activity came heavy precipitation from Tropical Storm Henri and Hurricane Ida, much of which impacted the U.S. Northeast, which had already experienced its third-wettest summer on record. Henri—one of a few storms in 2021 to have a non-tropical origin—made two landfalls in Rhode Island (on Block Island and near Westerly) at tropical storm strength and then weakened rapidly, but its slow-moving remnants doused the Northeast. Precipitation totals ranged from 4 to 9 inches across the region; in Brooklyn, New York, more than 9.5 inches of rain fell during Henri, a historic 1.94 inches of which fell within one hour in Central Park.

Hurricane Ida followed soon after, making two landfalls in Cuba and then one landfall in Louisiana as a Category 4 hurricane with 150 mph winds—tying it with 2020’s Hurricane Laura and the Last Island Hurricane of 1856 for the strongest hurricane to make landfall in the state. The storm landed about 60 miles south of New Orleans and soon after began weakening and moving inland and northward. Ida then merged with a frontal zone and produced prodigious rainfall across the Northeast. Up to 9 inches of rain from the storm fell over only a few hours across the Northeast; the same Central Park weather station recorded 3.15 inches of rainfall in one hour from Ida, breaking the value set a few days prior by Henri. What will the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season bring?

Pre-Season Forecasts

Various agencies and institutions issue pre-season forecasts of Atlantic hurricane season activity based on several large-scale and sub-seasonal factors. These factors affect key components for tropical storm formation, such as sea surface temperatures (SSTs), wind shear, atmospheric moisture, and vertical instability. When considered together, they paint a picture of what could happen during the Atlantic hurricane season. It is also important to note, however, that these factors are not constant, which means the hurricane season forecasts (Table 1) could change as the season progresses. Before the season started, seasonal and sub-seasonal factors indicated above average activity for the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season.

| Source | Named Storms | Hurricanes | Major Hurricanes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOAA | 14–21 | 6–10 | 3–6 |

| University College London | 18 | 8 | 4 |

| Colorado State University | 19 | 9 | 4 |

| The Weather Company | 20 | 8 | 4 |

| North Carolina State University | 17–21 | 7–9 | 3–5 |

| AccuWeather | 16–20 | 6–8 | 3–5 |

| Climatological Average (NOAA) | 14 | 7 | 3 |

Key Large-Scale and Sub-Seasonal Factors Considered in Pre-Season Forecasts

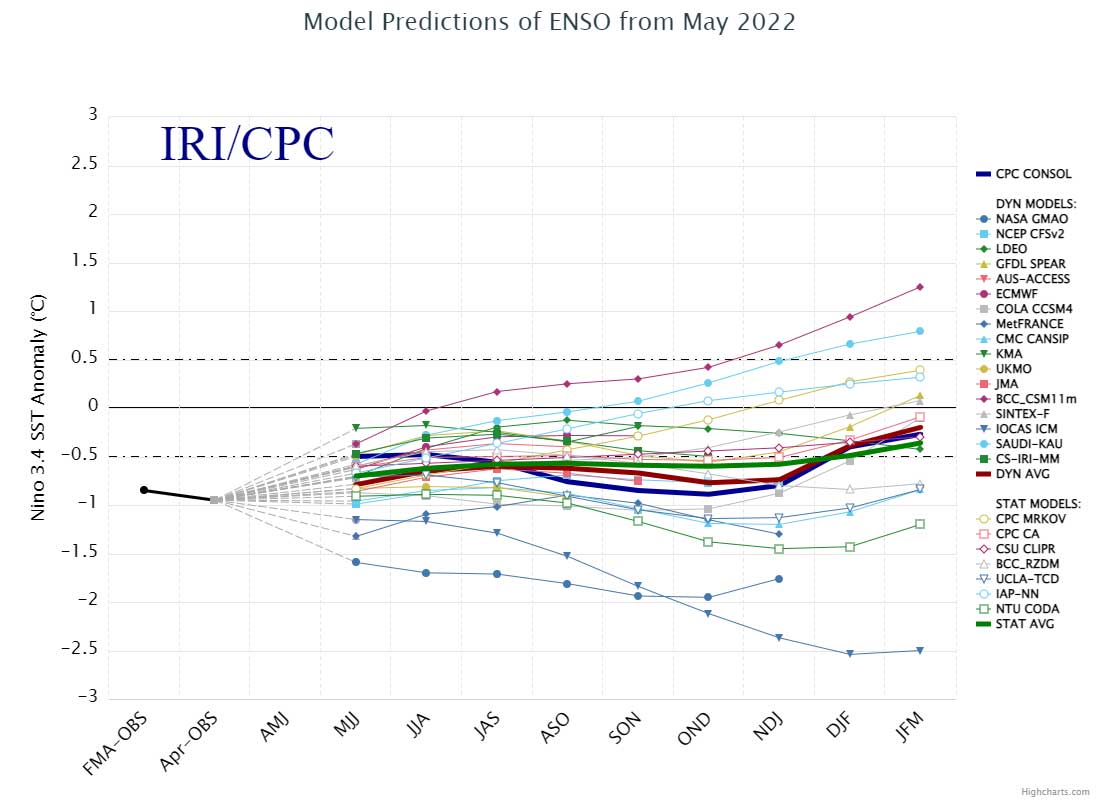

Perhaps the most well-known large-scale factor influencing pre-season forecasts is the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)—a coupled mode of atmospheric and oceanic variability in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Similar to the 2020 season, hurricane activity in the Atlantic basin during the 2021 season was amplified in part by La Niña—the cooler of ENSO’s phases associated with cooler SSTs in the eastern or central Pacific, which creates favorable conditions for cyclogenesis across the tropical Atlantic. This year, a weak La Niña is forecast for June through August and continuing into the fall/winter (Figure 1).

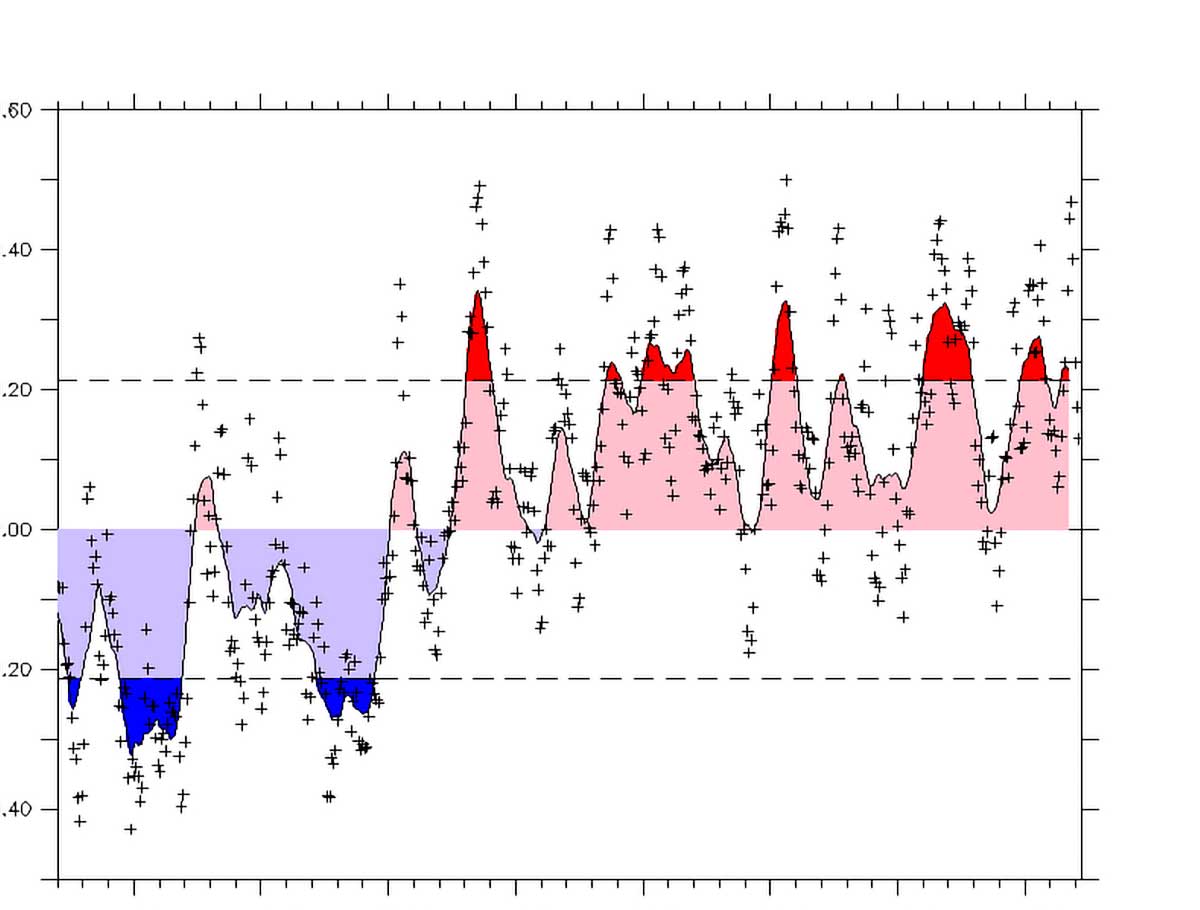

Also contributing to pre-season forecasts is the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)—a mode of variability of SSTs in the North Atlantic. The existence of the AMO, what drives it, and how it affects SSTs have been topics of recent research and require further study. Most recently, scientists have been debating the extent to which the AMO is an external mode of variability rather than an internal oscillation of the climate system, thus resulting in the renaming of the phenomenon as the Atlantic Multidecadal Variability (AMV). For pre-season forecasts, warm AMV periods tend to have warmer SSTs in the North Atlantic and correlate with increased tropical cyclone frequency in the Atlantic basin. The current warm AMV pattern has persisted since the mid-1990s (Figure 2).

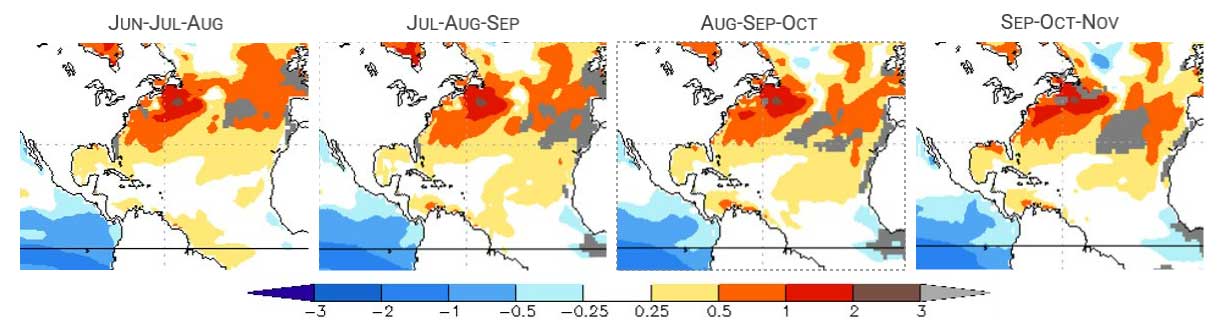

Warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures for the 2022 hurricane season have also been forecast by the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME)—a cooperative project operated by the NOAA Climate Prediction Center that compiles seasonal forecasts from various global modeling centers (Figure 3).

Making headlines this year as a contributing factor to potential hurricane activity is the Loop Current of the Gulf Stream. The Gulf Stream is an oceanic current that transports warm water from the Caribbean into the North Atlantic Ocean. As this current travels up past the Yucatan Peninsula and into the Gulf of Mexico it can form a loop deeper into the Gulf. According to NOAA, the Loop Current is extended to the north this year. When extended, the Loop Current typically sheds a large eddy of warm water that drifts westward from the Florida Strait toward Louisiana—a phenomenon that fueled both Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Ida 16 years later on their way to the Louisiana coastline.

Sub-seasonal factors fluctuate more frequently and add to the uncertainty of pre-seasonal forecasts. The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), for example, is based on the difference in sea-level pressure between the Icelandic Low and the Azores High and is only predictable about two weeks in advance. Lead times for forecasts of the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO)—an eastward-moving disturbance of clouds, rainfall, winds, and pressure capable of enhancing or suppressing convection in the tropics—are similar, at two to three weeks. As of the end of May, ensemble forecasts showed a potential for reinvigoration of the MJO in the Western Atlantic in the coming weeks, associated with increased convection.

Faster still is the three- to five-day cycle time of the Saharan Air Layer (SAL); this hot, dry layer of air laden with dust moves out over the moist surface air of the tropical North Atlantic Ocean and reduces atmospheric instability, increases vertical wind shear, and blocks radiation that can elevate SSTs. As of the end of May, predictions indicated the potential for SAL to be more active in the coming weeks in line with the usual seasonal cycle.

How Will 2022 Resemble the 2021 Hurricane Season?

Although each Atlantic hurricane season is unique, some aspects may remain the same from year to year. There were a few changes made in 2021 that will carry over into this year and beyond. First, the National Hurricane Center started issuing its first tropical weather outlook on May 15. Second, what constitutes an average season, which is based on a 30-year average and updated every 10 years, was updated by NOAA (Table 1). Third, the WMO retired the use of Greek letters to supplement the official list of storm names; the supplemental list of storm names will remain the same every year and only used if the official list used in rotation every six years is exhausted. One change in 2022, however, is that the name Ida was retired because of the death and destruction caused by this storm in the United States. The name that replaces Ida is Imani. Another thankful change is the end of a seven-year streak of pre-season development with the first named storm of this year—Tropical Storm Alex—happening after the official start of the Atlantic hurricane season.

Still relevant for 2022 also is the role of our changing climate on hurricane activity. Research has indicated that storms are weakening more slowly, as Hurricane Ida did last year when it maintained its peak intensity longer than other notable Louisiana storms. Storms that maintain their strength for longer periods can lead to larger wind speed damage footprints. Research has also shown that hurricanes are becoming wetter and moving more slowly, thus exacerbating inland flooding—which we saw with Hurricane Henri last year. Complicating things further is the impact of sea level rise on storm surge, as indicated by Verisk’s recent research study on the impact of climate change on U.S. hurricane risk, conducted in collaboration with the Brookings Institution and AXIS.

Be Prepared for the 2022 Atlantic Hurricane Season

What will the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season look like? Will we once again run through all 21 allotted storm names? Will we see hurricane landfalls? Will a major hurricane roar ashore? Will storms track far inland in the U.S. and inundate parts of the East and Gulf coasts? Will storm surge put a coastal city under feet of water? Will Louisiana, Texas, and the Northeast bear the brunt of the damage and Florida be mostly spared once more? Will a Caribbean island or the U.S. mainland be struck by a Category 5 hurricane?

The only definitive answer anyone can give to all these questions is: We don’t know. What is known, however, is that you can manage the risk posed by Atlantic hurricanes by using Verisk extreme event models for the U.S. and the Caribbean. In addition, the Verisk Real-Time Analytics Bundle is a solution that provides a full suite of data, imagery, and analytics. You can be ready when the next Atlantic hurricane landfall occurs.

Jeffrey Strong, PhD

Jeffrey Strong, PhD