Managing U.S. Terrorism Risk: A Look Back at the OKC Bombing

Mar 15, 2021

Editor's Note: The 2021 update to the AIR Terrorism Model for the United States is anticipated for release this summer. In this article, we describe the impacts of a recurrence of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing if it were to happen in today’s built environment using our updated model and with the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) in force. We also describe the capabilities in our updated model that make this possible and can be used to satisfy the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program (TRIP) data call.

The 9/11 airplane attacks on the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City and on the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., together with the crash of United Airlines Flight 93 in a Pennsylvania field, mark a historic tragedy 20 years ago that has since had multiple impacts not only on daily life but also the insurance industry. In addition to significant changes to air travel and building security, for example, the losses incurred by the attack brought the financial risks associated with terrorism to the fore. But 9/11 was not the first major terrorist act on U.S. soil; six years before 9/11, the Oklahoma City (OKC) bombing took place, blasting the heart of an American Midwestern city.

In this article, we discuss the difficult and sensitive topic of a what-if scenario involving the OKC bombing—what if this terrorist attack were to recur today in the current insurance and regulatory landscape. We also explain what the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act is and how it works, using a historical and a hypothetical example, and how users can manage their U.S. terrorism risk with the updated AIR U.S. Terrorism Model, anticipated for release this summer.

The 1995 Oklahoma City Bombing: The Deadliest and Costliest U.S. Terrorist Attack Until 9/11

Before the 9/11 terrorist attacks, which prompted the enactment of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA), the worst act of domestic terrorism in American history was perpetrated with a homemade bomb containing ammonium nitrate, diesel fuel, and other chemicals that was placed in a rented truck and parked immediately in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, OK, on April 19, 1995. The bomb was detonated shortly after 9:00 a.m. local time with the force of approximately 4,000 lbs. of TNT.

The Murrah building housed the offices for local branches of several federal departments, including the Social Security Administration; the Department of Housing and Urban Development; the Secret Service; the Department of Veterans Affairs; the Drug Enforcement Administration; and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. In total, the building housed offices where approximately 550 employees worked as well as a daycare center on the second floor. As a result of the blast, 149 adults and 19 children lost their lives that day, and 759 people were injured. The death toll could have been even worse, as only 361 people were inside the building at the time of the blast (Mallonee, et al., 1996).

While the area impacted by a terrorist attack is much smaller than, for example, the affected footprint of an earthquake or the storm track of a tropical cyclone, the death toll from a terrorist attack can be much higher. Slightly more than 300 buildings were affected by the OKC bombing, whereas after the M6.7 Northridge earthquake in 1994 there were more than 300,000 claims filed for single-family homes (PPIC, 2006), or roughly 1,000 times the number of buildings impacted by the OKC bombing, but there were less than half as many deaths, 72, and about 9,000 injuries. Until the 9/11 attacks, the OKC bombing was the deadliest act of terrorism on American soil.

In addition to the significant workers’ compensation and personal accident claims that resulted from this event, Verisk’s PCS® estimated that the damage to physical property totaled USD 125 million. One week after the blast, The Oklahoman reported that losses due to private property damage would likely be about USD 50 million—approximately USD 140 million in today’s dollars. This private property damage estimate excludes the losses that resulted from business interruption and workers’ compensation, as well as those associated with buildings self-insured by the federal government, such as the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building itself.

What if the OKC Bombing Were to Recur Today?

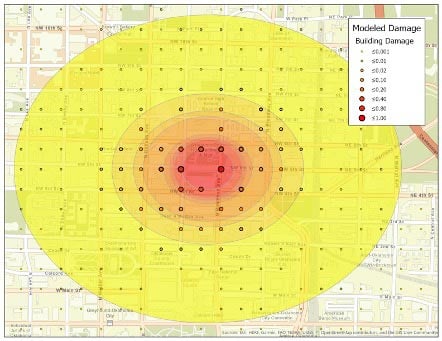

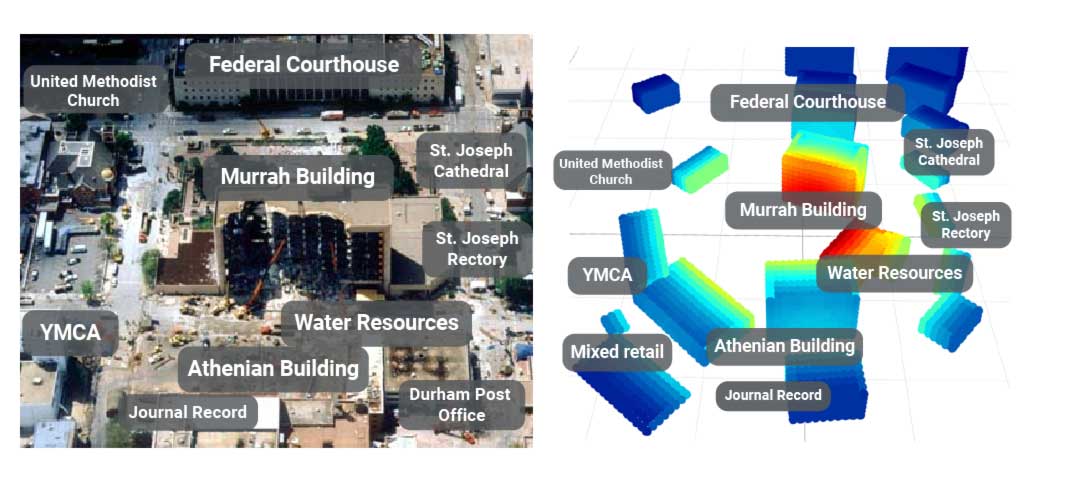

To model a blast similar in size and location to the OKC bombing recurring today, we used the updated AIR U.S. Terrorism Model and the 2019 version of AIR’s U.S. Industry Exposure Database (IED), which is modeled at a 90-meter resolution. The modeled damage footprint of this analysis is presented in Figure 1 where the individual point locations represent locations within the IED. The size and color of each point represent the modeled mean damage ratio for the building or buildings aggregated to that location. These colors also correspond to the building damage ratio radii that have been observed for the OKC bombing.

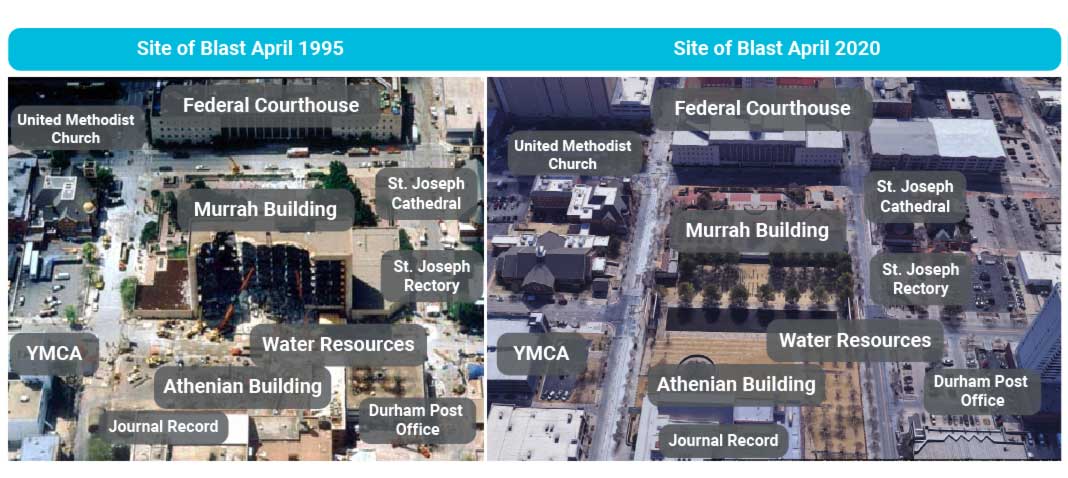

When evaluating the recurrence of a historic terrorism event, the analysis must first be sensitive to differences between the built environment at the time of the event and the exposure as it exists today. In this case, it was necessary to perform an audit of the buildings that existed in the vicinity of the blast in 1995 to understand which of them have been repaired, which have been replaced, and which have been removed from the current landscape.

Our analysis focused on six buildings closest to the blast that were severely impacted: the Alfred P. Murrah Building, the Water Resources Building, the YMCA, the Athenian Restaurant, the Durham Post Office, and St. Joseph’s Rectory (Figure 2). All of these were damaged beyond repair and needed to be completely replaced. Due to the classification of their sites as sacred ground because of the significant loss of life, however, the resources that had been housed in these buildings were relocated to other parts of the city at greater distances from the location of the blast. As a result, the built environment around the site of the blast today differs greatly from what it was in 1995.

Excluding the Murrah Building, which was self-insured by the government, the value of the private property that has subsequently been removed from the affected area immediately around the location of the blast is approximately USD 45 million (in 2019 dollar values). Using our updated model, we estimate that damage to private property would result in USD 98 million in insured losses. If we were to add the replacement value of the private property that was removed from the blast site between 1995 and 2019 (USD 45 million), to the modeled loss of USD 98 million, we would reach a total of USD 143 million, which is in close agreement with the estimates of observed losses due to private property damage (Jenkins, 2020).

What Is TRIA and How Does It Work?

In addition to understanding the potential impacts associated with a recurrence of this attack, part of an insurer’s responsibility for being financially prepared for any terrorism event is understanding the role TRIA would play.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, TRIA was signed into law in November 2002. Since then, TRIA has been extended or reauthorized four times by presidents representing both political parties. Most recently, TRIA was reauthorized in December 2019, one full year before it was set to expire, and it has been extended to the end of 2027. This legislation put into place a system by which losses from a certified act of terrorism are shared between the federal government and private insurers. In effect, it can be thought of as a blanket reinsurance policy—called the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program (TRIP)—by which losses over a pre-defined threshold are shared between the affected insurers and the federal government. The Department of the Treasury administers the program in conjunction with the Federal Insurance Office (FIO). There are many requirements delineated in TRIA that need to be satisfied to meet the classification of “a certified act of terrorism” and trigger TRIP. (We’ll discuss what types of events would trigger TRIP in the next section.)

According to Section 102(1)(A) of TRIA, an act of terrorism can be certified by the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury in consultation with the U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security and the U.S. Attorney General if it is deemed:

- to be an act of terrorism;

- to be a violent act or an act that is dangerous to

- human life;

- property; or

- infrastructure;

- to have resulted in damage within the United States, or outside the United States in the case of

- an air carrier or vessel; or

- the premises of a United States mission; and

- to have been committed by an individual or individuals, as part of an effort to coerce the civilian population of the United States or to influence the policy or affect the conduct of the United States Government by coercion.

Furthermore, Section 102(1)(B) makes certain exclusions to certifying an act of terrorism if

- the act is committed as part of the course of a war declared by the Congress, except that this clause shall not apply with respect to any coverage for workers’ compensation; or

- property and casualty insurance losses resulting from the act, in the aggregate, do not exceed USD 5,000,000.

Therefore, if the criteria set forth in Section 102(1)(A) are met and the aggregate insurance losses are above the USD 5,000,000 threshold, the act may be classified as a certified act of terrorism. Just because an act has been classified as a certified act of terrorism, however, does not mean that the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program (TRIP) will kick into effect. Additional criteria need to be met for TRIP to result in the federal government reimbursing commercial property and casualty insurers for losses incurred by the certified event. Specifically, the following two criteria need to be satisfied:

- The insurance industry’s aggregate insured loss is greater than USD 200 million

- An insurer has exhausted their TRIP deductible which is equal to 20% of their direct earned premium (DEP) in the year prior to the certified act of terrorism event from their covered TRIA lines of business

What types of events would trigger TRIP?

Given the many requirements that need to be satisfied for TRIP to be triggered, it can sometimes be unclear whether an event will result in co-insurance from the federal government. To understand this concept better, we will focus on the OKC bombing and a hypothetical event to determine how they would be analyzed with respect to TRIP.

1995 Oklahoma City Bombing

How would TRIP have responded to the 1995 Oklahoma City Bombing had TRIA been enacted at that time? With regard to the event itself, we understand that it (1) incited terror, (2) was a violent act that posed a threat to human life and property, (3) resulted in damage within the United States, (4) was not an act of war, and (5) resulted in insured property and casualty losses greater than USD 5 million. Depending on the motive of the perpetrators, a case could be made that the act was not carried out “as part of an effort to coerce the civilian population of the United States or to influence the policy or affect the conduct of the United States Government by coercion.” For the sake of this example, however, let’s assume that the intention of the bombers was to influence policy or affect the conduct of the United States Government. This event would therefore be classified as a certified act of terrorism.

The next layer of criteria that needs to be satisfied to trigger TRIP is the magnitude of the resulting losses. As mentioned previously, the insured losses from this event totaled USD 125 million in 1995—less than the USD 200 million threshold for the insurance industry’s aggregate loss (Section 102(1)(A)(i)), which would trigger TRIP. Therefore, TRIP would not have triggered if it had been in place at the time of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.

Hypothetical Attack on Rockefeller Center

Next, let’s assume that a certified act of terrorism occurred in June 2019 at New York City’s Rockefeller Center in Rockefeller Plaza and the weapon used was a van housing a bomb that exploded with the energy of 5,000 lbs. of TNT. Using the updated AIR U.S. Terrorism Model and the 2019 industry exposure, we estimate that this hypothetical event would result in USD 35.7 billion of insured property and business interruption losses. This amount of loss would be sufficiently above the USD 200 million threshold required to trigger TRIP.

Once TRIP has triggered, each affected insurer would be required to calculate their unique deductible based on 20% of their terrorism DEP for the year prior to the certified event taking place. In this case, that would be 20% of the terrorism DEP for 2018. With that information, it is possible to calculate the loss-sharing that would take place between each affected insurer and the reimbursement they would receive from the federal government.

What Makes the Updated U.S. Terrorism Model Best in Class?

The man-made peril of terrorism poses unique risks when compared to some natural catastrophes. It may exhibit cyclic behavior influenced by, for example, a national political climate, significant religious events, or anniversaries of past terrorist attacks. And it may be coupled in the near future with the impact of the worsening climate crisis on some socio-economic classes globally (Somers, 2019). Terrorism has also been accelerated in recent years by social media platforms and online resources spreading misinformation and radicalizing individuals. These circumstances drive the need for insurers to acknowledge, understand, and account for terrorism.

The updated U.S. Terrorism Model provides the following capabilities and more, which make it a powerful tool for assessing terrorism risk:

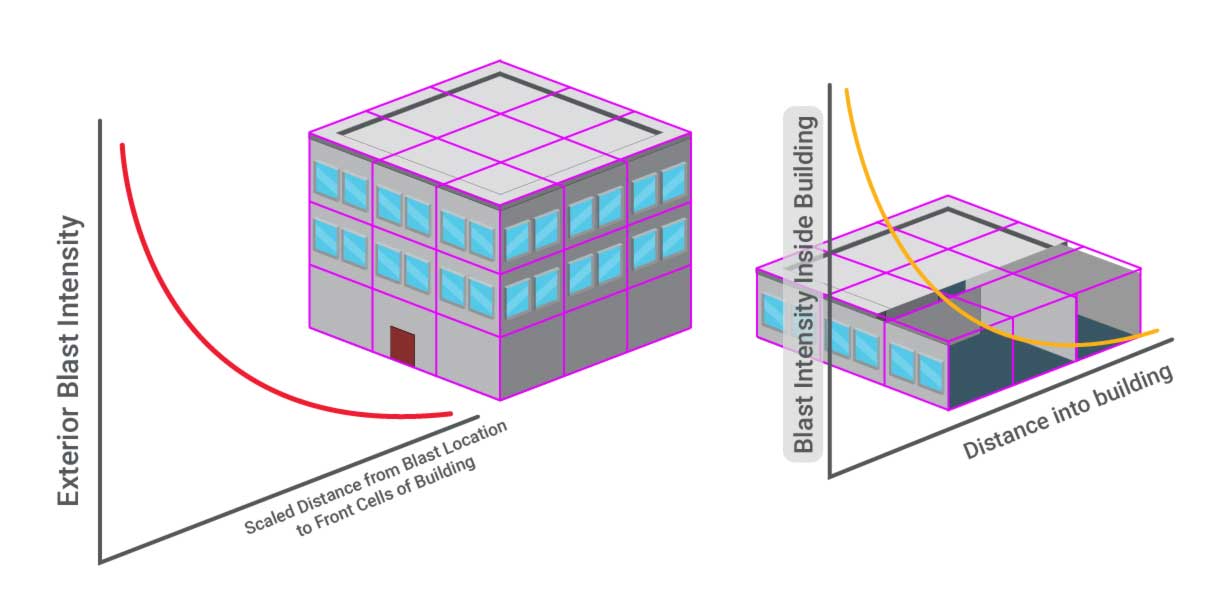

- 3D Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations have been conducted to improve intensity propagation through a variety of urban environments

- Multiple intensity measures are used to provide a realistic estimation of damage using a damage function surface

- The loss calculation framework and cellular damage aggregation approach permit detailed loss results for a specific floor of interest

- The addition of the 10-ton Medium Truck blast size allows users to simulate a greater variety of scenarios

Figure 3 illustrates how the updated AIR U.S. Terrorism Model operates at the cellular level. The diagram shows how a blast’s intensity propagates from the blast location to the front of a modeled building at multiple discrete locations, demarcated by the purple grid lines. This intensity propagation is modeled with respect to scaled distance from the blast location to the building site. Once the blast waves impact the exterior of the building, there is a drop in pressure and pressure impulse as they penetrate the façade and continue to attenuate within the building’s interior. This interior intensity is modeled with respect to the distance into the building.

Every component of this updated model has been validated with observations from historical events and published literature to ensure confidence in the modeled results. An example of this can be seen in Figure 4, which compares the extent of damage caused by the blast in the left panel with the 3D footprint of damage simulated by the model in the right panel, where warmer red colors denote building cells that experienced high damage and the cooler blue colors denote building cells that exhibited little to no damage. To generate this 3D footprint, an exposure of 26 buildings closest to the blast in 1995 was input to the updated U.S. Terrorism Model. The development version of the model can output these granular intermediate results that are then aggregated to estimate the mean damage ratios for each building.

Using the updated AIR U.S. Terrorism Model, (re)insurers can estimate the potential property, business interruption, workers’ compensation, and personal injury losses that can arise from acts of terrorism. The deterministic event modeling capabilities in Touchstone® allow you to select a blast size and location to analyze the impact it will have on your specific book of business. This complements the exposure aggregation capabilities provided by Touchstone’s Geospatial Analytics Module, which can leverage dynamic ring analysis to identify locations corresponding to maximum exposure concentrations. The ability to leverage both of these capabilities makes the U.S. Terrorism Model in Touchstone best in class for estimating terrorism risk in the United States.

Resources

Alfred P Murrah Federal Building. (n.d.). Retrieved from Wikipedia.

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2020). Global Terrorism Index 2020: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Sydney. Retrieved January 26, 2021, from visionofhumanity.org.

Jenkins, J. P. (2020, 8 6). Oklahoma City Bombing. Retrieved from Encyclopedia Britannica.

Mallonee, S., Shariat, S., Stennies, G., Waxweiler, R., Hogan, D., & Jordan, F. (1996). Physical Injuries and Fatalities Resulting from the Oklahoma City Bombing. Journal of the American Medical Association, 382-387.

Somers, S. (2019). How Terrorists Leverage Climate Change. Environmental Change and Security Program, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Retrieved January 26, 2021, from newsecuritybeat.org.

Andrew O’Donnell, Ph.D.

Andrew O’Donnell, Ph.D. Kulbhushan Joshi, Ph.D.

Kulbhushan Joshi, Ph.D.