Putting Jebi's Insured Losses in Context: A Look Back at Historic Japan Typhoons

Sep 17, 2019

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Toa Reinsurance Company, Limited, for their Japan’s Insurance Market 2019 publication. The insured loss amounts given in this article include only residential, commercial, mutual, and auto lines of business; they exclude loss adjustment expenses, loss from Miscellaneous (e.g., marine, accident, etc.) demand surge, business interruption, etc. The USD amounts given in this article are based on an exchange rate of JPY 1 = USD 0.0091.

Globally, 2018 was a costly year for catastrophes; the Camp Fire in California topped the list of insured losses last year, followed by Hurricane Michael at number two, and Typhoon Jebi in the number three spot. For the Japanese insurance industry, 2018 was the costliest year for natural disasters since 2011 when the M9.0 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami struck. Jebi is responsible for most of the insured losses from the five major events to impact Japan in 2018: the Western Japan floods in late June/early July; the M5.5 Osaka earthquake on June 18; the M6.6 Tomakomai earthquake on September 6; and Typhoon Jebi in early September, followed by Typhoon Trami later that month. At the time of this writing, industry estimates for Jebi’s insured losses alone hover around USD 13 billion.

Although Jebi is firmly established as Japan’s biggest typhoon-related insurance and reinsurance loss on record, much greater losses are possible. Japan is prone to natural disasters and the decade that followed World War II saw numerous large-scale events, including the Nankai earthquake in 1946, Typhoon Kathleen in 1947, the Fukui earthquake in 1948, Typhoon Ida in 1958, and Typhoon Vera in 1959. If Ida or Vera were to recur today, for example, each would result in higher losses than those of Jebi. More recently, Typhoon Mireille in 1991 was Japan’s costliest typhoon at the time and if it were to recur today its losses would be of a similar order of magnitude to Jebi’s losses. In this article, we take a look back at historic storms—precipitation-dominant (Kathleen, Ida), surge- and wind-dominant (Vera) and wind-dominant like Jebi (Mireille, Bart, Songda)—to understand Jebi’s losses in the context of historic Japan typhoon losses.

Typhoon Kathleen

On September 15, 1947, Typhoon Kathleen made landfall in Kanagawa Prefecture, just south of Tokyo. One-minute sustained winds at landfall were estimated at 120 km/h—just barely equivalent to a Category 1 hurricane. In Shizuoka Prefecture, south of Kanagawa, one-minute sustained winds exceeding 88 km/h (tropical storm strength) were reported. Having weakened by the time of landfall, wind damage was restricted to towns along the immediate coast.

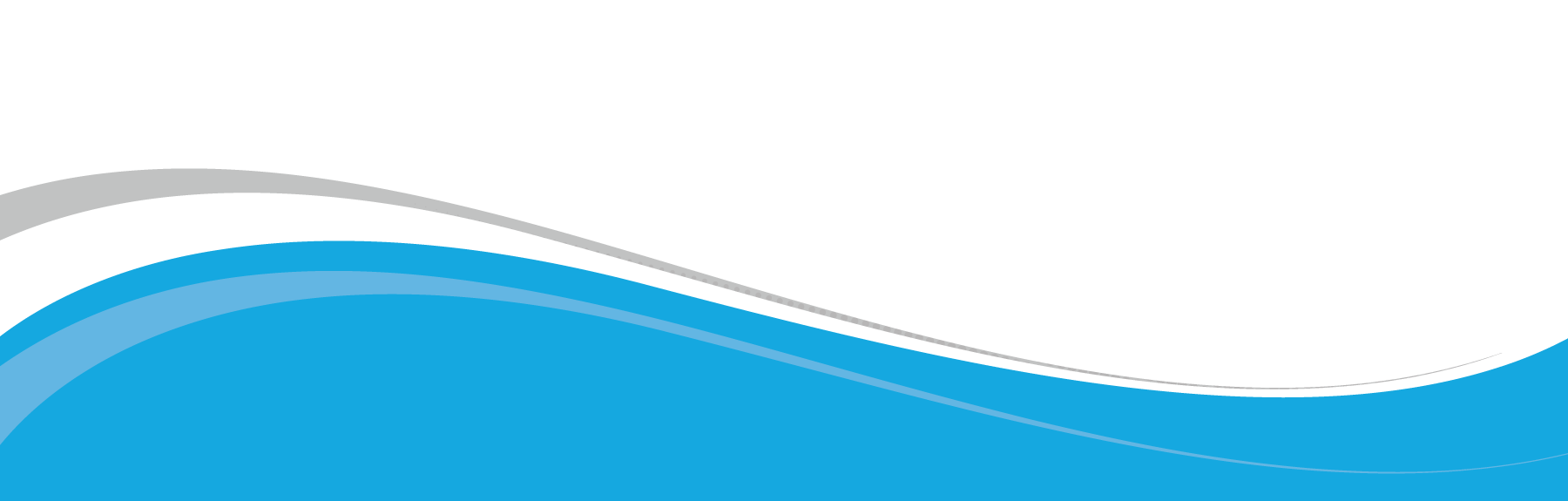

More extensive, however, was the damage from precipitation-induced flooding from Typhoon Kathleen, which dropped between 300 and 800 mm of rain in the Tone River basin in just two days (Figure 1)—from September 13 to 15—yielding the highest flood discharge ever observed. North and east of Tokyo, several dikes were breached and embankments suffered failures, resulting in severe flooding along the Tone River, particularly in Kurihashi. More than 303,000 buildings were inundated, and 2,000–4,000 people were killed.

Typhoon Kathleen is still regarded as one of Japan’s costliest and most devastating precipitation-induced flood disasters. AIR estimates that if Kathleen were to recur today, insured losses would total approximately JPY 1,294 billion (USD 11.8 billion).

Typhoon Ida

On September 26, 1958, Typhoon Ida struck Japan’s Kanagawa Prefecture on the island of Honshu. While there was some wind damage, the vast majority of Ida’s damage was caused by the deluge of rain from the Izu Peninsula to the capital city of Tokyo and beyond (see Figure 2), which led to flooding and mudslides.

Ida’s rains drenched the region during the course of two days, causing several rivers east of Tokyo to burst their banks and flood the suburbs there. Some of the worst destruction and loss of life, however, was along waterways in the western suburbs. Ida’s heaviest rains fell west of Tokyo, inundating the headwaters in the mountains and river valleys, triggering flooding and mudslides. The area of the Izu Peninsula around the Kano River (Kanogawa) experienced some of the highest rainfall rates.

AIR estimates if Ida were to recur today, it would result in insured losses of approximately JPY 2,466 billion (USD 22.5 billion). Typhoon Ida remains one of the country’s most devastating precipitation-induced flood disasters.

Typhoon Vera: Japan’s Most Destructive Typhoon and Its Impact on the Insurance Industry

Ida preceded Typhoon Vera—the costliest weather-related disaster in Japan’s recorded history—by only one year; a significant portion of the damage was the result of storm surge. On September 26, 1959, a monstrous Category 4 storm with winds near 240 km/h came ashore west of Ise Bay in south-central Japan. The storm was dubbed Vera.1 Its record-high storm surge crashed over seawalls and breached coastal dikes hundreds of years old. Vera moved northeast over land toward Ise Bay, where its winds drove bay water toward Nagoya Port. The port experienced storm surge of nearly 4 metres at 9:35 p.m. local time. Dikes caved immediately, giving people in Nagoya and surrounding villages little time to flee. The city of Nagoya was devastated in just three hours; its harbor—strewn with bodies, debris, and timber from a local timber factory—was subsequently described as a “sea of dead.”

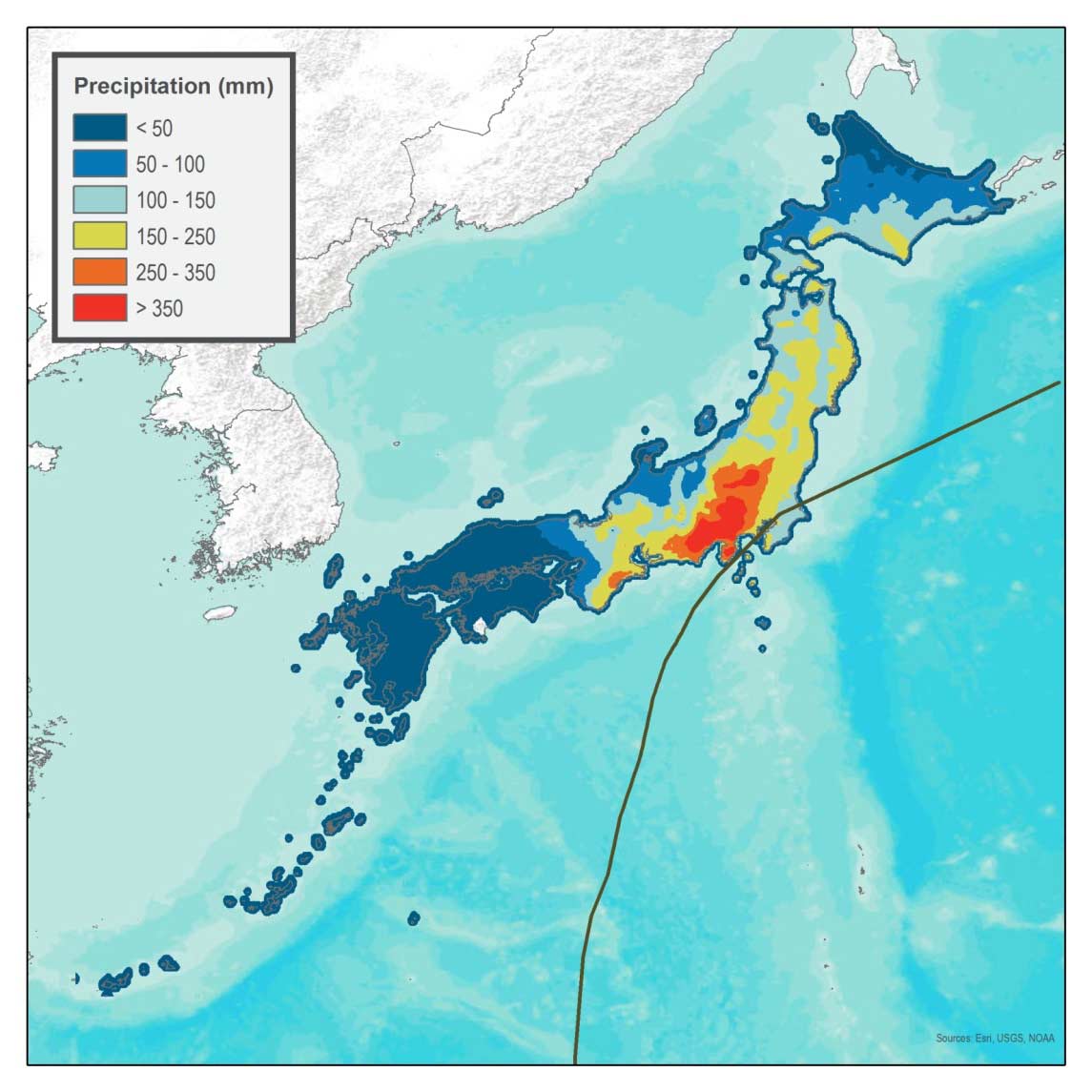

Vera tracked quickly across Honshu, losing little strength over land (See Figure 3). In the small village of Nagano in central Japan, high winds ripped the roofs from hundreds of traditionally constructed wooden homes. Heavy precipitation swelled rivers so greatly that they spilled over their banks. Landslides were widespread. Conditions remained treacherous even after Vera’s departure. Muddy water continued to pour through breaches in dikes on the south-central coast for several days until they were finally repaired. Because the area just north of Ise Bay is at or even below sea level, some districts remained flooded even 100 days after the storm.

Altogether, Typhoon Vera flooded more than 360,000 homes, 190,000 of which were submerged2 (Oda, 2006). Another 830,000 homes sustained some level of damage. The storm killed an estimated 5,000 people and injured 66,000. Much of the damage was in Aichi and Mie prefectures. AIR estimates if Vera were to recur today, it would result in insured losses of approximately JPY 1,943 billion (USD 17.7 billion), caused mostly by wind (JPY 1,819 billion, USD 16.63 billion).

Vera became the event used by insurers and reinsurers to define the reserve for a 70-year return period event. An amendment to the enforcement regulations of the Insurance Business Law on April 1, 2005, requires insurers to base their catastrophe reserves for windstorm or flood on recurrence of Typhoon Vera.3 This increases the minimum windstorm return period for reserving and reinsurance purposes from 20 years to 70 years.

Typhoon Mireille: Typhoon-Related Insured Loss Record-Setter

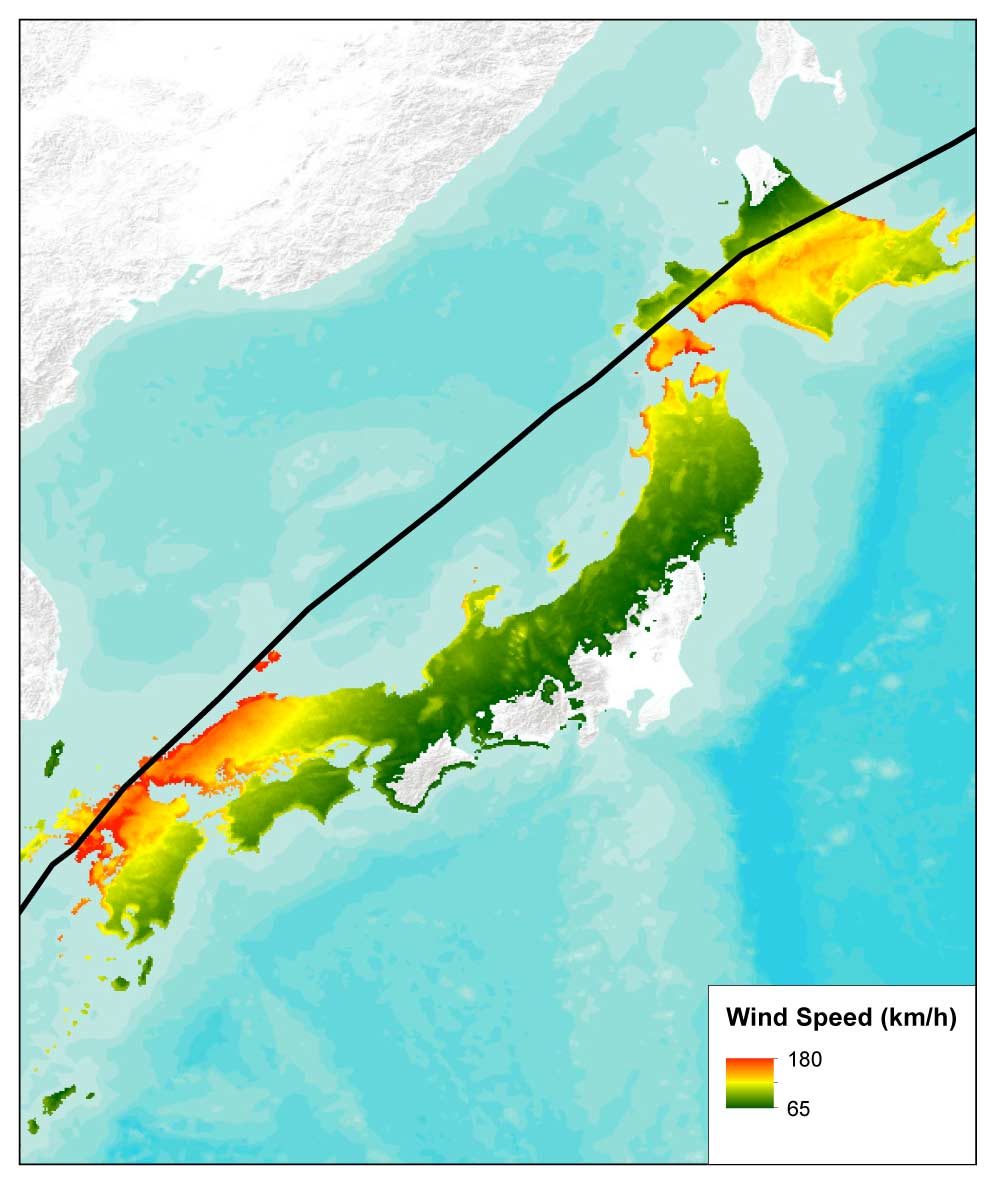

Typhoon Mireille whipped across Japan with winds in excess of 160 km/h (Figure 4), causing damage in 41 of Japan’s 47 prefectures, destroying more than 170,000 houses and resulting in the largest insured loss claim ever paid for a typhoon-related loss in Japan’s modern history. AIR estimates Mireille’s recurrence today would result in insured losses of JPY 1,115 billion (USD 10.18 billion), caused mostly by wind (JPY 1,040 billion; USD 9.5 billion). Mireille remained Japan’s costliest typhoon for decades, until Jebi.

On September 27, when Mireille made landfall in Kyushu’s Nagasaki Prefecture, it was the third typhoon of the 1991 season to affect Japan in just two weeks. While interaction with Typhoon Nat may have influenced Mireille’s eventual track, it was not the only factor instrumental in Mireille’s rise to the top of Japan’s insured loss charts.

Mireille took a track typical of other typhoons that have caused major damage on Japanese soil. Furthermore, as is typical, its strongest winds at landfall were on the right, or eastern, side of the storm (which is a result of the combination of counterclockwise rotational winds and forward motion).

Other typhoons that have caused significant wind damage in Kyushu include Bart in 1999 and Songda in 2004, both of which took paths very similar to Mireille’s (Figure 5), but would each cause less in insured losses than Mireille. Bart would cause JPY 675 billion (USD 6.17 billion) if it were to recur, caused mostly by wind (JPY 639 billion, USD 5.84 billion); Songda would cause JPY 778 billion (USD 7.11 billion) in insured losses if it were to recur, also mostly caused by wind (JPY 754 billion, USD 6.89 billion).

The large losses from Mireille—as compared to those from Songda—were in part a result of Mireille’s lower central pressure at landfall (even though both storms exhibited identical central pressure values three hours later, and nearly identical radii of maximum winds). Processes related to extratropical transitioning were also prominently at work in Mireille, much more so than they were in Songda (or in Bart). These processes changed Mireille’s wind field, and in doing so, contributed to higher losses.

Typhoon Jebi: Managing Japan Typhoon Risk Today

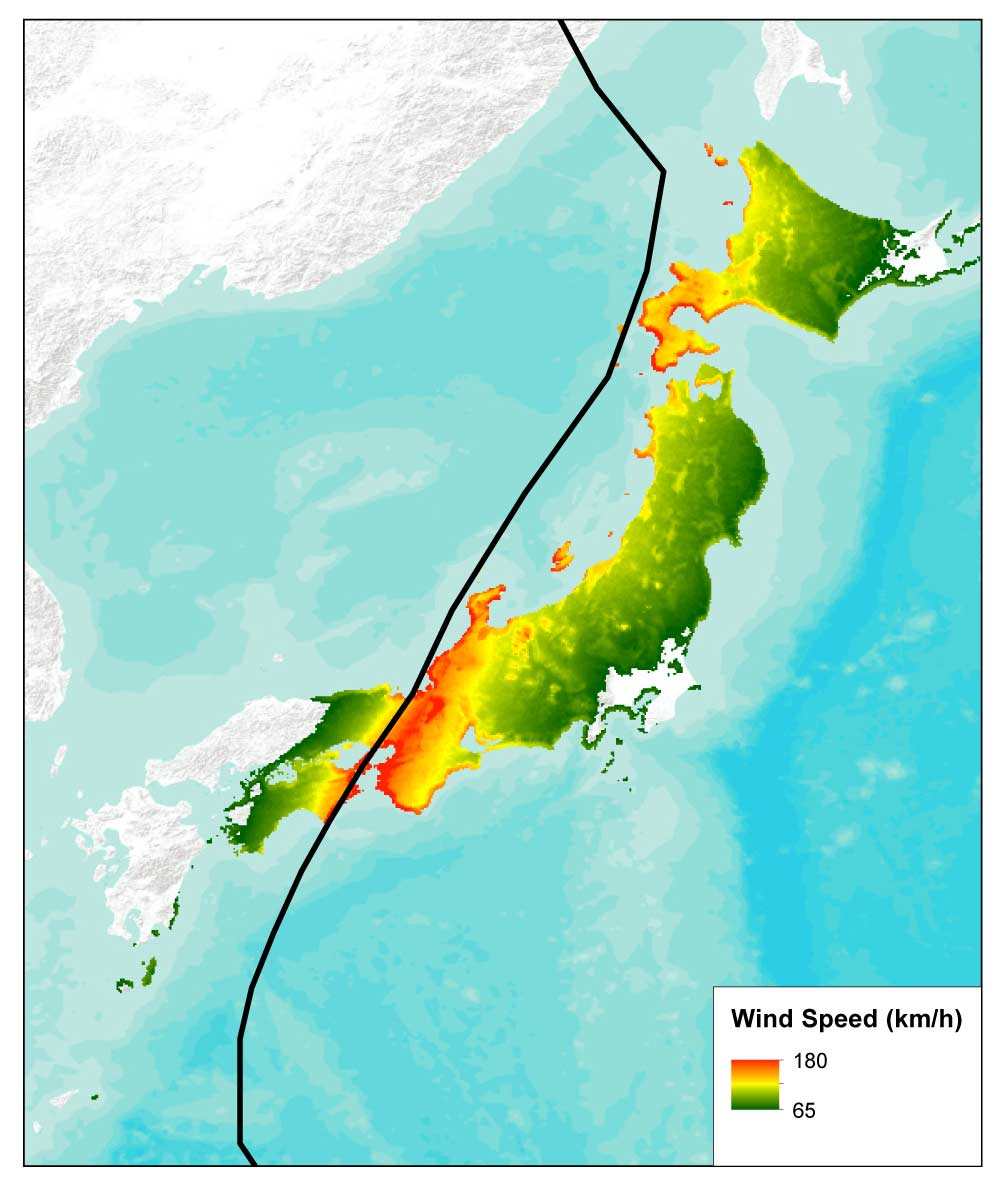

Typhoon Jebi initially struck Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, on September 4, 2018. The equivalent of a Saffir-Simpson Category 3 hurricane when it made landfall, Jebi was the most powerful typhoon to hit Japan in 25 years (Figure 6). A second landfall followed near the city of Kobe, 30 km west of Osaka, on neighboring Honshu. Major cities in the Kansai region, among them Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe, were brought to a halt. The typhoon caused major damage to buildings and infrastructure, seriously impacted shipping and transportation, and led to significant business interruption. While Jebi’s insured losses have already set a record, losses would have had more of an impact if insurers were not required to base their reserves on a recurrence of Typhoon Vera.

The year 2018 will surely reinforce not just to industry newcomers, but even to those who have spent their careers assessing and managing catastrophe risk, that it is important to prepare for a wide range of scenarios to respond effectively when disaster does strike. Preparing for large losses before they occur by using model scenarios to probe a portfolio’s strengths and weaknesses is critical to continued solvency and resilience. Jebi is not an extreme tail event; far greater losses are possible (Figure 7). The AIR Typhoon Model for Japan includes Extreme Disaster Scenarios (EDS) that represent unlikely, but scientifically plausible, scenarios that cannot be captured by standard stochastic modelling techniques. (Re)insurers can perform detailed loss analyses against these “grey swan events” so that companies can grasp the possible impact on their business (Figure 7).

*Jebi’s losses reflect industry estimates as of May 2019.

No catastrophe model can predict what the next natural disaster will actually be or when it will occur. This fundamental uncertainty makes it all the more important for companies to use catastrophe models to prepare for such losses. The full range of scenarios a model can generate—simulating several perils that can impact Japan—provide a unique and important perspective on an organisation’s risk. The careful analysis of model results can help risk managers prepare for many contingencies—thus ensuring that another Jebi, for example, will not be entirely unexpected.

Ultimately, catastrophe models—such as the AIR Typhoon Model for Japan, one of a suite of AIR models for Japan—help organisations evaluate the full range of potential events so that they can manage the risk effectively.

References

1 The Japan Meteorological Agency, which assigns numbers rather than names to typhoons, made an exception in this case after the fact, calling it the Isewan Typhoon because of its destruction of the Ise Bay (wan) region.

2 Submersion indicates flooding to the first floor level.

3 Privatization of the Japanese insurance market didn’t happen until 1996; regulating catastrophe reserves was not a priority until nine years later, in 2005, the year after 10 typhoons—more than twice the annual average—made landfall in Japan.

Milan Simic, Ph.D.

Milan Simic, Ph.D.