Parts of eastern Australia have been experiencing a succession of storms lately producing heavy rainfall and serious flooding; what is going on? The flooding along the southeast coast has been the worst in more than a decade. Roads were closed, power outages occurred, thousands of homes were inundated—some more than once—more than 60,000 people are under evacuation orders, and at least 21 lives have been lost.

It is summer in the Southern Hemisphere, but it has been an unusually wet season in Australia. One news report bemoaned that there had only been 24 clear days since the start of the year and Brisbane, the state capital on the southeast coast of Queensland, has had its wettest summer since local records began in 1899. To the south Sydney, the capital of New South Wales and Australia’s most populous city, has had the wettest start to any year since local records began in 1956, with some locations receiving more than 860 mm—a total not usually reached until August.

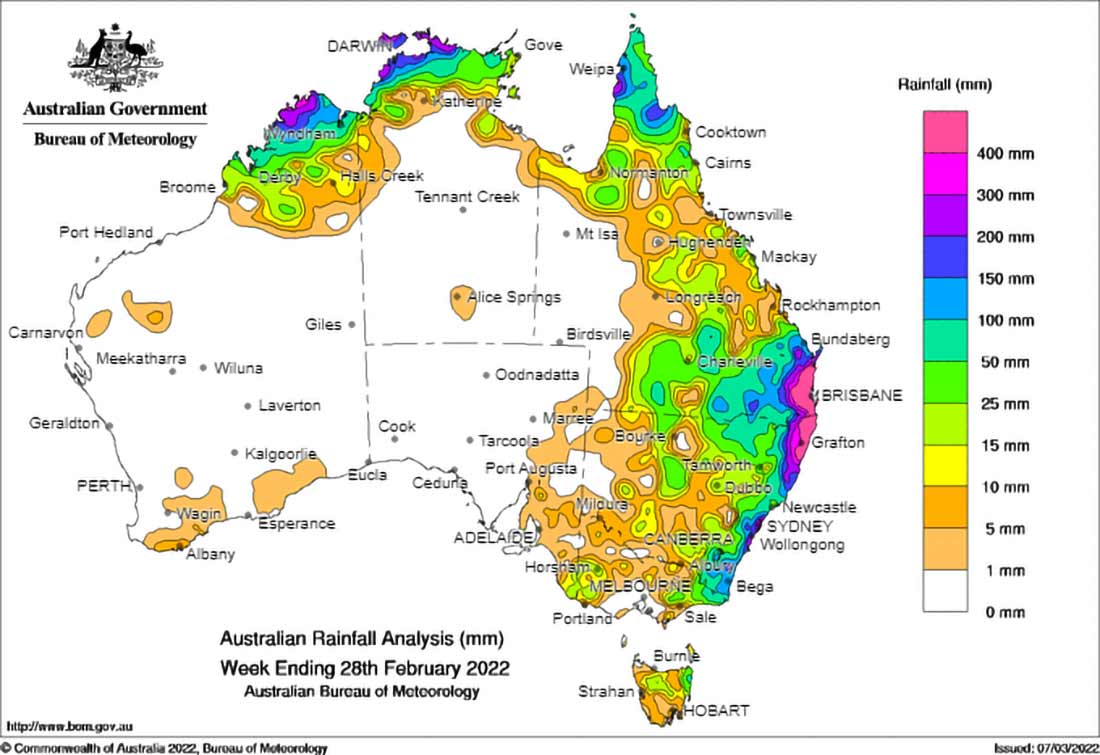

The heavy precipitation began on February 22 in Queensland and hasn’t let up yet (Figure 1). On February 22, for example, the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) reported 300 mm of rain falling in 6 hours near Gympie on the Mary River about 110 miles north of Brisbane, prompting flood warnings. Heavier rain fell that evening with isolated rainfalls of 450 mm, with 292 mm within two hours reported. During the next three days a slow-moving system dropped as much as 700 mm in total in some areas. Between February 26 and 28, for instance, Brisbane received 676 mm of rain—roughly half of its average annual rainfall; totals of 300 to 400 mm were reported by the BOM on February 28 across southeast Queensland.

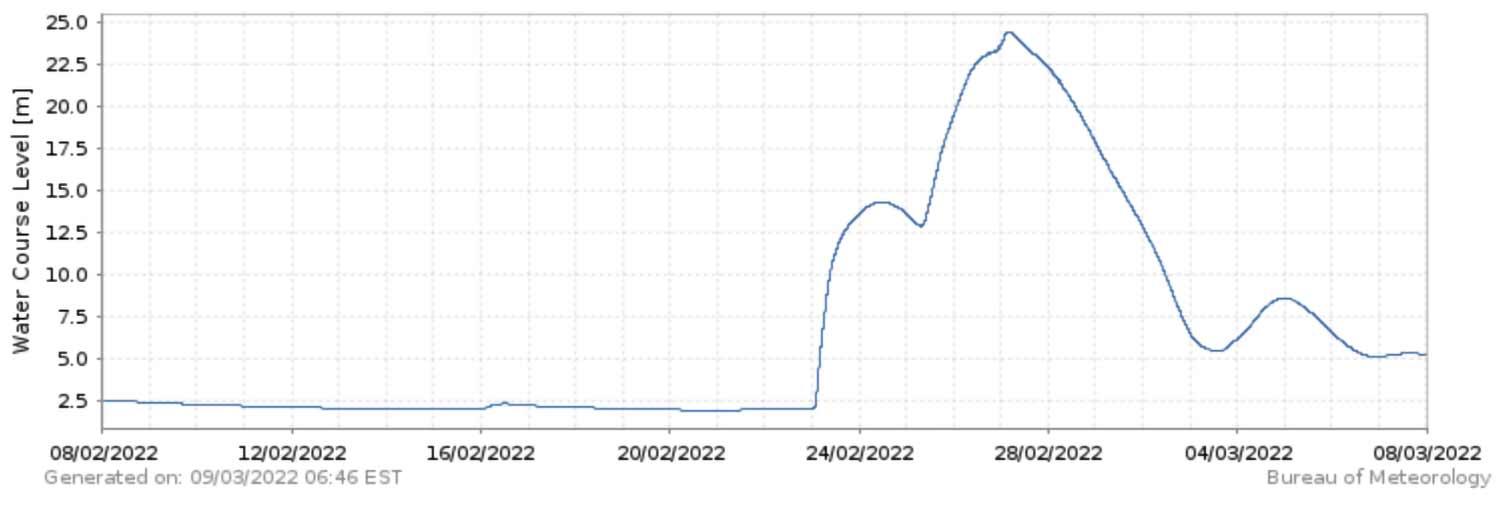

As water levels in rivers and streams rose, rapidly in some locations, flood warnings were issued for Queensland rivers, including the Mary, Noosa, Maroochy, Mooloolah, Pine, Caboolture, and Brisbane, and several waterways burst their banks. In low-lying Gympie, as the Mary River passed its major flood stage (17 meters) and crested at 22.98 meters, about 700 residents were ordered to evacuate (Figure 2). Unusually heavy precipitation and flooding were also experienced to the south in New South Wales, particularly in the Northern Rivers region. On February 28, for example, the Wilsons River peaked at 14.11 m, breaking previous records set in 1954 and 1974.

Severe thunderstorms with large hail, damaging winds, and locally heavy rainfall continued to impact parts of southeastern Queensland and northeastern New South Wales for the next few days. With the ground saturated and waterways and dams at or near capacity, additional major flood warnings were issued, and more flash flooding and landslides occurred. As another weather system brought yet more rain parts of Sydney flooded. Of the 11 major storage dams in the vicinity of Sydney, one reached 97.4% capacity, another reached 99%, and the remainder reached 100% capacity. Flooding impacted Sydney’s western suburbs when one of these, the Warragamba Dam, began to overspill on March 5; the recreational Manly Dam, built in 1892, overtopped on March 8.

Why Is This Happening?

The chief culprit for the intense precipitation is La Niña. Most of us are familiar with La Niña because of its impact on the Atlantic hurricane season. La Niñas typically develop on the heels of El Niños every three to seven years. A La Niña tends to develop during the Southern Hemisphere’s autumn, strengthen during its winter and spring, start decaying in the mid to late summer, and dissipate in the fall. While sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific are cooler during a La Niña event, the waters closer to Australia are warmer than usual and parts of the country can experience particularly wet weather.

But the ongoing La Niña began in June of 2020, and has lasted 21 months and counting. The one before that began in mid-2017 and lasted a full year. While it is not unusual to experience back-to-back La Niñas—they have become more frequent, more intense, and longer lived. From 1977 to early 1998 for example, there were only five La Niñas, with two lasting 12 months or longer and none lasting 18 months. From mid-1998 to the present there have been 10 events with five lasting 12 months or longer and four past 18 months. Multiyear La Niña events such as the one ongoing have been associated with some of Australia’s worst floods. While even longer records show a more mixed picture, some studies suggest that climate change will enhance future events, bringing a double whammy because of additional moisture that will condense from warmer air temperatures.

Australia’s prime minister, Scott Morrison, declared a national emergency on March 9 to expedite relief measures, but the wet weather is far from over. Summer has only just ended in Australia and La Niña is likely to persist into late autumn (May)—which is when winter begins in the Southern Hemisphere and the eastern states normally experience their wettest weather. The wet weather won’t begin to diminish until late winter (July or August), so Queensland and New South Wales could have an extremely wet year.

Read the blog “Who Knew Severe Thunderstorm Risk Was Such a Big Deal in Australia?”