In September 1961, a reconnaissance plane investigating Typhoon Nancy reported one-minute sustained winds of 343 km/h (215 mph)—one of the strongest winds ever measured in a tropical cyclone. Recorded as the storm neared its peak, this figure is likely an overestimation as wind speed measurements in this era used inadequate technology and are today commonly perceived to be biased high. Nevertheless, Nancy was still a remarkably intense and destructive typhoon.

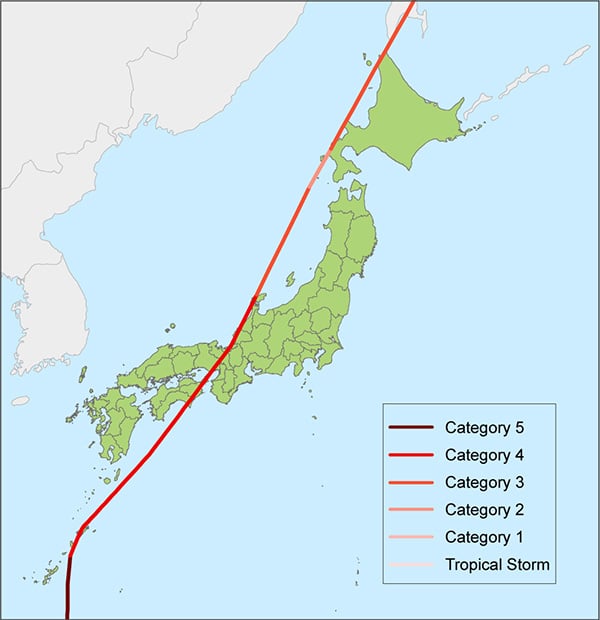

The tropical cyclone formed west of the Marshall Islands on September 7 and rapidly intensified into a powerful system as it moved to the west; it was an explosive deepener—a storm that intensifies more than 24 hPa in a single day. Nancy followed a smooth westerly track, passing 85 miles south-southwest of Guam and curving slightly toward the north. After reaching its peak intensity as a super typhoon on September 12, however, it started weakening and began a more pronounced recurvature not previously forecast. As it passed 40 miles East of Okinawa the subtropical ridge steering it broke down and it started moving steadily northeastward heading directly for Honshu, the main island of Japan.

Nancy made landfall on September 16 with one-minute sustained winds estimated at 208 km/h (129 mph), passing directly over Cape Muroto on Shikoku, the second smallest of Japan’s five main islands. Accelerating to a forward speed of 100 km/h (65 mph) as it continued northeastward, it then made a second landfall near Osaka, the second-largest metropolitan area in Japan, crossed Honshu rapidly to emerge into the Japan Sea, and continued in the same direction to clip Hokkaido. Nancy finally exited into the Sea of Okhotsk as a tropical storm and became extratropical on September 17.

During a period of 9 days and 18 hours (during which warnings were also issued for typhoons Olga and Pamela) a total of 40 warnings were issued for Nancy. The typhoon’s surface winds remained higher than 115 mph for eight days and had the Saffir-Simpson Scale existed at the time it would have been considered the equivalent of a Category 5 storm for five and a half days—longer than any other tropical cyclone on record.

Wind Damage Throughout Japan

Because of Nancy’s fast forward motion, precipitation-induced flooding was minimal but damaging winds occurred throughout Japan, with Osaka being particularly hard hit. Because its track traveled across some of the most densely populated areas the damage caused was extensive. The death toll would likely have been higher had it not been for timely warnings that allowed for adequate preparation, but with 202 people killed or missing (and 4,972 reported injured) Nancy was still Japan’s sixth deadliest typhoon to-date.

Half of the crops in the southern part of Guam were destroyed as Nancy passed by and there was extensive crop and structural damage and flooding in Okinawa. On the three main islands where Nancy made landfall there were 11,539 homes destroyed, 32,604 damaged, and 280,078 flooded; 650,000 people were left homeless. There were 566 bridges swept away and 1,146 landslides reported; more than 1,000 ships sank or were blown ashore. Prior to Nancy, Typhoon Vera in 1959 was the costliest weather-related disaster in Japan's history.

Nancy was not the first typhoon to make landfall near Cape Muroto and will surely not be the last. The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) only rarely gives storms special designations but dubbed Nancy the "Second Muroto Typhoon"—the first having killed 3,066 people in 1934 and left parts of Osaka in ruins. More recently, in 2018 Typhoon Jebi, the most powerful typhoon to strike Japan since Yancy in 1993, took a slightly more northerly track through Osaka Bay but otherwise followed a remarkably similar track from Cape Muroto, across Honshu, and toward Hokkaido.

All of Japan at Risk

Typhoon activity poses a risk of damage to nearly all of Japan. The greatest risk, however, is from the occurrence of a landfall event in central Japan, between the cities of Osaka and Nagoya. The Kansai metropolitan area, which includes Osaka, has an estimated population of 19 million (2021), and Nagoya has an estimated population of 9.5 million (2021). Such high concentrations of people make the risk of loss of life and destruction of property relatively high in these areas. Significant losses would also result if a typhoon struck the island of Kyushu (estimated population of 14.3 million in 2018); although the density of insured exposures is relatively low there.

As the number and value of properties in Japan’s risk-prone areas continues to grow, it is essential for companies operating in this market to have the tools that will help effectively manage and mitigate the financial risks from future devastating typhoons.