What would the impact of a historical catastrophe be if it were to recur today? This question is frequently asked when conducting present-day catastrophe risk assessments. To better answer this question, researchers commonly adjust monetary losses to account for changes in inflation and development over time. This adjustment is called normalization, also known as loss trending.

Trending Catastrophe Losses Using Capital Stock

Numerous methods exist to normalize catastrophe losses. The most common method normalizes catastrophe losses by accounting for inflation, population, and gross domestic product (GDP). Adjusting for inflation accounts for changes in the value of currency over time, while increases in population and GDP suggest that more people and property are located in exposed areas. GDP is used to approximate the value of capital stock (i.e., property and other fixed assets) due to the lack of readily available data on capital stock. Recent research, however, suggests that capital stock is preferred over GDP for the purpose of normalization as it directly measures the value of damageable property.

AIR developed a global method for normalizing catastrophe losses to present-day values using capital stock (Alstadt, Hanson and Nijhuis 2021). This approach normalizes catastrophe losses by adjusting for the change in the value of capital stock from the year the event occurred to the normalized (e.g., current) year. Capital stock is defined as the total value of fixed assets purchased for long-term use and includes dwellings, other buildings and structures, and machinery and equipment. In effect, capital stock is a measure of the replacement cost of fixed assets, accounting for both inflation and real changes in value.

National capital stock is derived using the perpetual inventory method and a time series of annual gross fixed capital investment (a component of GDP). The perpetual inventory method is an accounting method that measures new additions to capital stock as well as subtractions when something is taken out of service or demolished. Capital investment data is available from the United Nations (U.N.) for more than 200 countries and areas of the world.

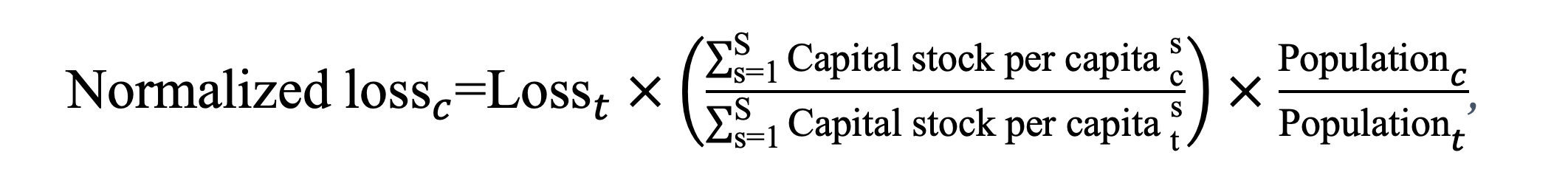

Using the change in capital stock values over time, catastrophe losses are normalized as follows:

where c is the current year losses are normalized to, t is the year in which the loss occurred, and capital stock is capital stock of stock types (residential, nonresidential structures, and nonresidential equipment). The population term adjusts for changes in population in the damaged area. Inflation is implicitly included in the capital stock values. Using this equation, losses are normalized using the ratio of the value of current-year capital stock to loss-year capital stock.

Results from an analysis of normalized catastrophe losses finds that this approach produces results that are broadly similar to established normalization methods and may be preferred over methods that use GDP in place of capital stock. This approach provides reliable normalized losses for most countries; however, additional considerations need to be made for analyzing losses in countries with limited or poor data quality, instable currencies, or fixed exchange rate or other currency control systems. We demonstrate the challenges with normalizing catastrophe losses in these types of economies with a case study of Venezuela.

A Case Study of Venezuela

Current economic conditions in Venezuela

Analyzing past catastrophe losses in Venezuela is complicated by the country’s troubling economic conditions. Venezuela has been in an economic and political crisis for several years, with economists regarding the fall as the single largest economic collapse outside of war in at least 45 years (Kurmanaev 2019). The causes behind Venezuela’s collapse are complex and have been attributed to years of poor governance, political corruption, and misguided economic policies.

The crisis accelerated in 2014, coinciding with falling global oil prices and the election of President Nicolás Maduro following the death of Hugo Chávez. The fall in oil prices helped trigger a recession and runaway inflation, which continue today. Venezuela’s economic decline has led to a devastating decrease in household purchasing power, food and medicine shortages, and the mass emigration of millions of Venezuelans.

Hyperinflation has rendered Venezuela’s currency nearly worthless. Inflation has exceeded 100% each year since 2015, peaking at over 65,000% in 2018 (International Monetary Fund 2021). In 2018, Venezuela’s currency, the Bolívar Fuerte (VEF), was replaced with a new currency, the Bolívar Soberano (VES). The currency replacement attempted to address Venezuela’s currency instability by cutting five zeros off the old currency. Bloomberg began measuring inflation in real-time by tracking the cost of a cup of coffee at a bakery located in the city of Caracas, the nation’s capital. In the past year, the price of a café con leche jumped from VES 250,000 (USD 1.27) to VES 5,918,500 (USD 1.91), an increase of 2,267% (Bloomberg 2016).1

Hyperinflation and Venezuela’s Currency Exchange Rate System

Hyperinflation, combined with Venezuela’s fixed currency exchange system, distorts the value of Venezuelan currency relative to the U.S. dollar (USD). From 2003 to 2018, the Venezuelan government pegged the value of Venezuelan currency to the U.S. dollar, introduced currency controls that limited who could buy and sell foreign money, and set maximum prices for basic necessities (Wilson 2003). The currency regime created a black market for U.S. dollars and a parallel exchange rate.

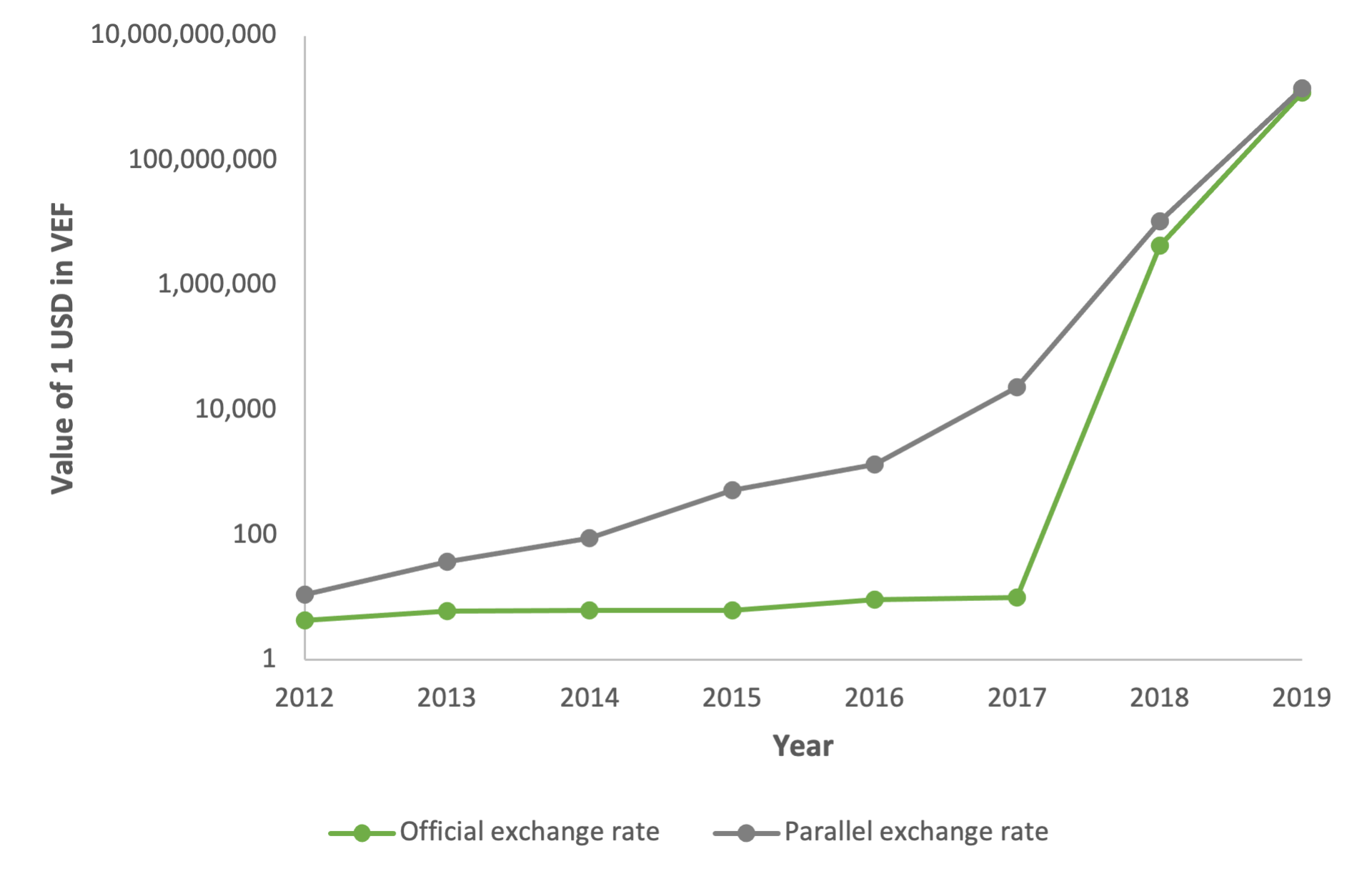

Figure 1 shows the value of 1 USD in VEF using the official and parallel (black market) exchange rates from 2012 to 2019. Fast-rising inflation beginning in 2014 increased demand for U.S. dollars on the black market. The official exchange rate, which was artificially controlled by the government, did not adequately adjust for inflation. This resulted in a wide and fast-growing gap between the value of Venezuelan currency using the official and parallel exchange rates. In 2018, the government devalued the official exchange rate by more than 99% to help stabilize the economy. Currency controls were loosened in 2019, authorizing local banks to carry out the purchase and sale of foreign currency by individuals and businesses. These policy changes narrowed the gap between the official and parallel exchange rates, although a gap remains.

Considerations for Normalizing Catastrophe Losses in Venezuela

Hyperinflation and Venezuela’s currency exchange rate system raise issues for catastrophe loss normalization. First, losses are often reported in U.S. dollars. The distortions created by the fixed exchange rate will not adequately capture hyperinflation of the Venezuelan currency and may distort both nominal and normalized losses. The parallel exchange rate may be better suited for converting losses between local currency and U.S. dollars. Second, the price level of Venezuelan currency relative to U.S. dollars needs to be factored into measuring capital stock in USD. Normalization should attempt to account for annual changes in the relative value of capital investment in local currency and U.S. dollars.

To demonstrate how hyperinflation and the fixed exchange rate system will affect catastrophe loss normalization, we normalize losses from a 2012 Venezuelan flood using three approaches. All three methods use the change in the value of capital stock to normalize losses. The first method (Method 1) adjusts for the change in the value of capital stock in local currency (VEF). Normalized losses are converted between VEF and USD using official exchange rates.

The second approach (Method 2) adjusts for the change in the value of capital stock in U.S. dollars. Capital stock is derived using annual gross fixed capital investment in USD and is obtained from the United Nations. The U.N. data accounts for exchange rate distortions and reflects price levels relative to the United States. This adjustment is made for countries with fixed exchange rates and countries going through a period of high inflation where exchange rates are not adjusted adequately to reflect changes in their prices relative to prices in the United States. Normalized losses are converted between VEF and USD using official exchange rates.

The third approach (Method 3) adjusts for the change in the value of capital stock in black market U.S. dollars. Capital stock is derived using annual gross fixed capital investment converted to USD using parallel exchange rates. Parallel exchange rates are average annual exchange rates reported by Dolar Today, an American website that publishes daily parallel (black market) exchange rates. Normalized losses are converted between VEF and USD using parallel exchange rates.

Normalizing Catastrophe Losses in Venezuela

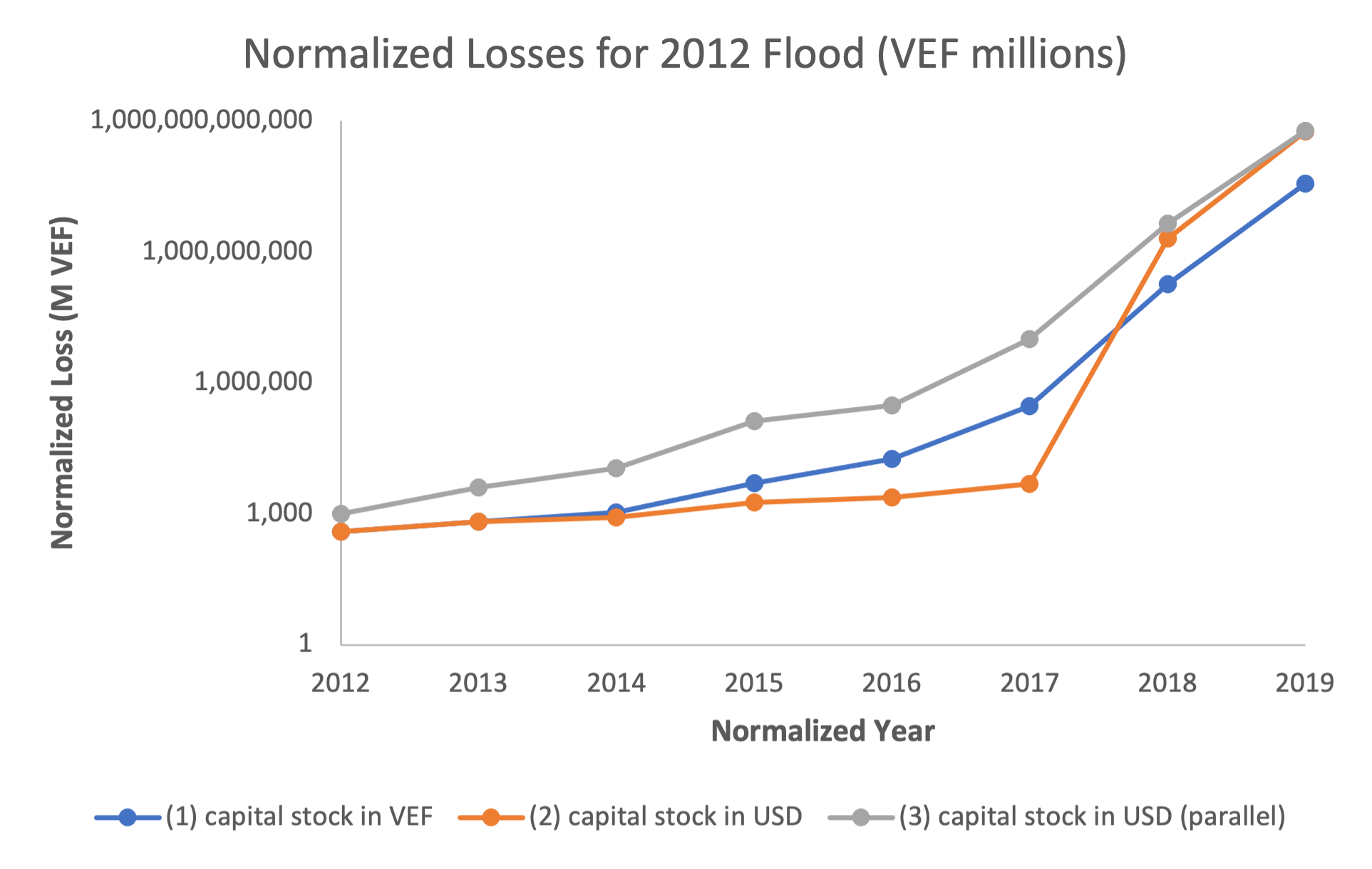

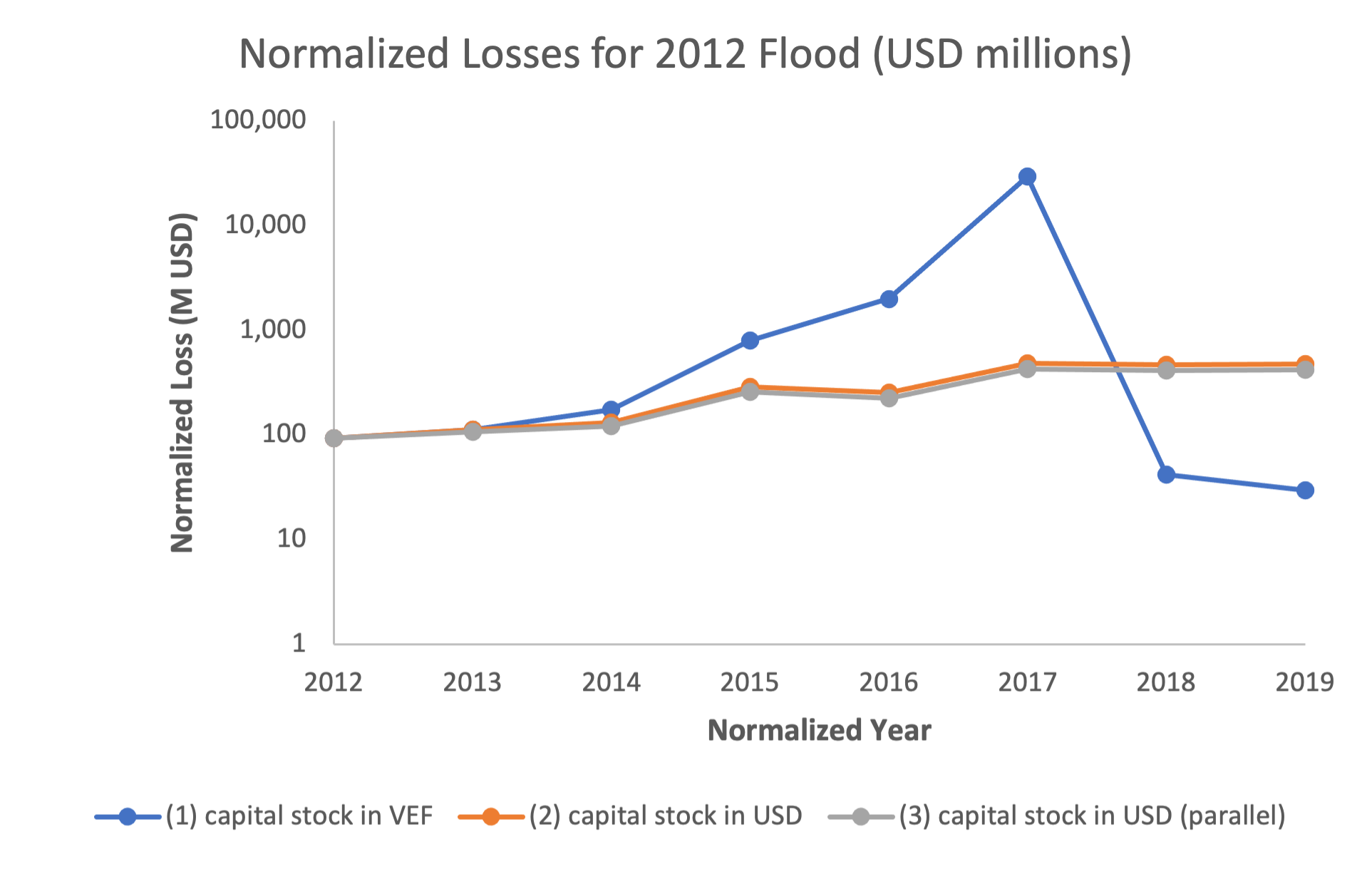

Figure 2 shows normalized losses of the 2012 flood event in VEF and USD by year for each normalization approach. The flood, a result of heavy rainfall throughout the country, caused a reported USD 93 million in damage (Aon Benfield 2012). For each normalized year, normalized losses reflect the adjusted cost of the flood, accounting for inflation and real changes in capital stock value for that year.

In Venezuelan currency, the nominal loss in 2012 was equivalent to VEF 399 million using the official exchange rate or VEF 1 billion using the parallel exchange rate. Across all three methods, normalized losses in VEF increased rapidly by 2019, reflecting hyperinflation of the local currency; however, the rate of change and magnitude of loss varies by method.

- Method 1, which normalizes losses by the change in capital stock value in VEF, results in normalized losses that begin to increase rapidly after 2014, following the onset of hyperinflation.

- Method 2, which normalizes losses using capital stock value in USD (price-adjusted by the U.N.) shows a slower increase in normalized losses from 2014 to 2017, jumping in 2018. These normalized losses reflect the distortions between VEF and USD created by the fixed exchange rate regime.

- Method 3, which normalizes losses using capital stock value in black market USD (parallel exchange rate) shows growth in normalized losses consistent with Method 1; however, losses are systematically higher, reflecting the greater value of U.S. dollars on the black market.

In terms of U.S. dollars, the increases in normalized losses are more modest compared to local currency. Method 1 reflects the distortions between VEF and USD created by the fixed exchange rate and hyperinflation. Between 2014 and 2017, losses are systematically higher and increase faster than the other methods, suggesting that the fixed exchange rate overvalued VEF relative to USD during this period. By 2018, the official exchange rate was adjusted and devalued Venezuela’s local currency, resulting in a substantial decline in normalized losses in 2018 and 2019. Methods 2 and 3, which both use price-adjusted values of capital stock in USD for normalization, show similar patterns in normalized losses.

Implications for Global Catastrophe Loss Normalization

Normalizing past catastrophe losses using the change in the value of capital stock presents an alternative approach to loss normalization. This approach provides reliable normalized losses for most countries; however, additional considerations must be made for analyzing losses in countries experiencing hyperinflation or under fixed exchange rate systems. The case study of Venezuela flood losses demonstrates that both nominal and normalized losses can become distorted by a fixed exchange rate system that does not adequately adjust for hyperinflation. Globally, this suggests that it is important to ensure that normalization accounts for actual changes in prices for the country concerned, whether losses are normalized in local currency or U.S. dollars.

1The price of a café con leche are from June 2020 and June 2021. Prices in VES were converted to USD using daily exchange rates from XE.com on June 4, 2020 and June 5, 2021.

2From 2012 to 2017, the official exchange rate is from the United Nations National Accounts Main Aggregates Database and is defined as the annual average of exchange rates as reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). On August 20, 2018, the official currency in Venezuela changed from VEF to VES. The official exchange rate for 2018 is the annual average of daily exchange rates reported by the Federal Reserve with VES exchange rates converted to VEF. The official exchange rate for 2019 is from the United Nations and converted from VES to VEF. Parallel exchange rates are average annual exchange rates reported by Dolar Today with VES exchange rates converted to VEF.

References

Alstadt, Brian, Anthony Hanson, and Austin Nijhuis. 2021. "Developing a global method for normalizing economic loss from natural disasters." Manuscript submitted for publication.

Aon Benfield. 2012. "May 2012 Global Catastrophe Recap. "http://thoughtleadership.aon.com/Documents/201206_if_monthly_cat_recap_may.pdf.

Bloomberg. 2016. Venezuelan Cafe Con Leche Index. December 15. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2016-venezuela-cafe-con-leche-index/?terminal=true.

International Monetary Fund. 2021. "World Economic Outlook Database." https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/April/select-country-group.

Kurmanaev, Anatoly. 2019. "Venezuela’s Collapse Is the Worst Outside of War in Decades, Economists Say." The New York Times, May 17. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/17/world/americas/venezuela-economy.html.

Wilson, Scott. 2003. "Chavez Changes Currency System." The Washington Post, February 7. Accessed June 18, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2003/02/07/chavez-changes-currency-system/9e429076-bd61-4eae-8158-cc7bd5a25337/.

AIR’s Consulting Services help you succeed in today’s fast-paced world