In this blog, we summarize the impacts of COVID-19 on the food supply chain and commodity prices. We will discuss how the team of agricultural risk modelers at AIR can help you assess and mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 on your book of business.

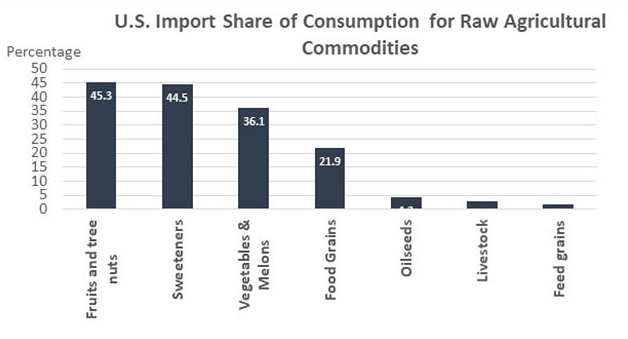

About 15% of U.S. food consumption relies on imported products. Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of raw agricultural commodities imported by the U.S.

Food Supply Chain

The U.S. agricultural sector has been through a rough patch. Last year food and beverage industries contributed USD 481.4 billion in GDP. The restaurant industry's projected sales for 2020 were twice as large as the prior year. Then the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), states, and local health officials set and implemented health and safety protocols for the restaurant industry that have been in place since March. Lockdowns impacted the restaurant, hospitality, and transportation industries, causing the demand for meat products, sugar, and other raw and manufactured agricultural products to shrink.

According to some reservations companies, 25% of the restaurants may not reopen after the pandemic ends. This significant drop in the number of restaurants will impact the entire food supply chain: farmers, butchers, wineries, transportation, and delivery companies.

Fruits, Nuts, and Vegetables: COVID-19 hit the U.S. in March when there was minimal fruit and vegetable production in progress. As spring progressed, however, field and packing facilities started to work in many states. Unlike grain crops, which rely on machinery, fruits and vegetables are picked by hand and packaged manually. Migrant farmworkers are essential assets to agricultural producers because in developed countries like the U.S. only 5% of the population works in agriculture.

With pandemic travel restrictions reducing the mobility of migrant workers the price of high value specialty crops could have increased significantly. The USDA reacted promptly and managed to keep current H-2A visa program going and arranged to issue visas for additional migrant farmworkers, which maintained the labor force and reduced potential impacts.

California, a state that supplies more than a third of the country's vegetables and two-thirds of the fruits and nuts is, however, among the top U.S. states for COVID-19 cases and deaths. The number of migrant farmworkers reported positive for COVID-19 is rising as the U.S. experiences the peak of the summer produce season. Shortage in labor could mean some fruits and vegetables will rot, which would translate into reduced supply and higher prices at the grocery stores.

Sweeteners—Sugar: Severe drought conditions in India and Thailand impacted the sugar harvesting season and led to a price increase in the first quarter of 2020. In Brazil, the depreciation in oil prices and a decrease in ethanol demand encouraged farmers to switch gears and plant sugar. Then global sugar demand from food industries decreased. Government lockdowns, for example, reduced consumption of products containing sugar, such as soft drinks sold at concessions in arenas and stadiums. Even though world production is expected to rebound, sugar consumption will recover at a much slower pace. USDA reported a second quarter price of 5.98 cents per pound for refined sugar price on July 2, which is down from 17.51 cents per pound at the end of first quarter this year.

Livestock: Lack of automated machinery along with icy and damp environments increased the chances of virus transmission among workers in processing plants, forcing meat producers to close their facilities. By May pork and beef production had decreased by 35% compared to a year earlier, resulting in rationing at the grocery stores and price increases. Meat producers were left with no option but to euthanize hogs, chickens, and cattle, costing the industry billions of dollars in losses.

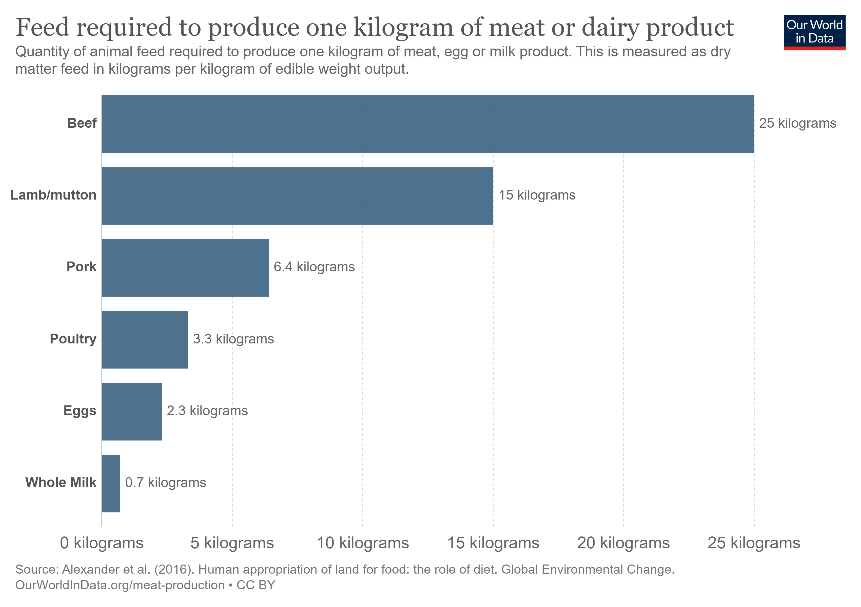

Putting livestock on low-calorie, low-protein, and high-fiber diets has been the most effective risk-mitigation strategy, as animals become unsellable once they grow past their target weight. Figure 2 shows the quantity of animal feed required to produce one kilogram of meat, eggs, or milk. By placing livestock on high-fiber food, farmers can delay harvest by up to 3 months for cattle. Meat producers and processing plants have begun to recover but significant losses have been incurred.

Food and Feed Grains—Corn: Farmers this year have the highest reported stock of corn since 1993. In the U.S., most of the corn is used as the main energy ingredient in livestock feed. But it is also processed into a multitude of food and industrial products including starch, sweeteners, corn oil, beverage and industrial alcohol, and fuel ethanol. As discussed above, due to COVID-19, the U.S. herd of poultry, swine, and cattle has decreased due to disrupted meat production. Travel restrictions and work from home reduced demand for gasoline and consequently, the need for ethanol, an additive to gasoline. In August the USDA forecast an average farm price of USD 3.10 per bushel, the lowest corn price since 2006, which is not going to cover the farmers' production costs.

Commodity Prices

Revenue protection with the harvest price option is a policy type offered by the U.S. Federal Crop Insurance Program to most commodity crops in the U.S. The main feature of the policy is that it covers the revenue of the producer and pays revenue based on the higher of two prices—the projected and harvest prices—both of which are based on futures trading data. Most producers of major crops choose to insure against their expected revenue with this product.

The policies for major crops and their projected prices are established in February. Since then, the expected prices have decreased due to the pandemic. Corn’s projected price was USD 3.89 per bushel for the 2020 season, with the December futures price at USD 3.35 in July (3.54 on August 25); as noted above the season-average corn price is currently projected by WASDE to be USD 3.10. The soybean projected price in February was USD 9.17, which fell to USD 8.43 on March 18 as COVID-19 information was incorporated. November soybean futures are now trading for USD 9.00. The U.S. season-average soybean price is forecast to be USD 8.35 per bushel in the USDA’s August 12 World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates.

How Can AIR Worldwide Help?

While the economic impact from COVID-19 is going to be significant, the implications of the outbreak for the crop insurance industry are still unfolding.

AIR’s Multiple Peril Crop Insurance Model for the U.S. provides a probabilistic yield and price catalog that maintains spatial and temporal correlations of crop losses. The U.S. MPCI model allows users to think about different yield and price subsets of the catalog, which can help define what loss ratios might look like for different books of business.

CropAlert® tracks the growing season in the U.S., China, Canada, and India and provides updates on key risk assessment data—from baseline yield, to recent weather impacts on crops, to loss estimates—necessary for a clear view of your agricultural risk. You can use this information to evaluate the impact of these conditions on your portfolio performance, assess the sufficiency of reserves or, if conditions warrant, pursue retro cover.

Maximize profit potential and make better decisions with AIR crop models and services