Most hurricane damage is caused by wind and storm surge, but inland flooding is a major source of loss too. Tropical cyclones can cover vast areas and soak them with heavy precipitation as they move forward. The slower the hurricane’s forward speed the higher the potential for heavier rainfall. Some research has shown that tropical systems may be slowing down in forward speed. The 2017 and 2018 Atlantic hurricane seasons set records for rainfall totals and highlighted the impact that hurricane-induced precipitation and the resultant inland flooding can have on losses in the United States.

Hurricane Harvey

In August 2017 Hurricane Harvey became the wettest hurricane in U.S. history, inundating the Houston area with up to 60 inches of rain—33 trillion gallons of water in total. Harvey came ashore as a Category 4 storm but stalled the next day some 50 miles southeast of the San Antonio region. With little forward movement the system’s training bands of heavy rainfall persisted over the Houston area leading to a widespread 20 to 40 inches of accumulation across the region. The National Weather Service office in Houston officially recorded 43.38 inches. The massive amount of precipitation had to go somewhere; unfortunately, unable to drain or soak away quickly enough, it inundated the city.

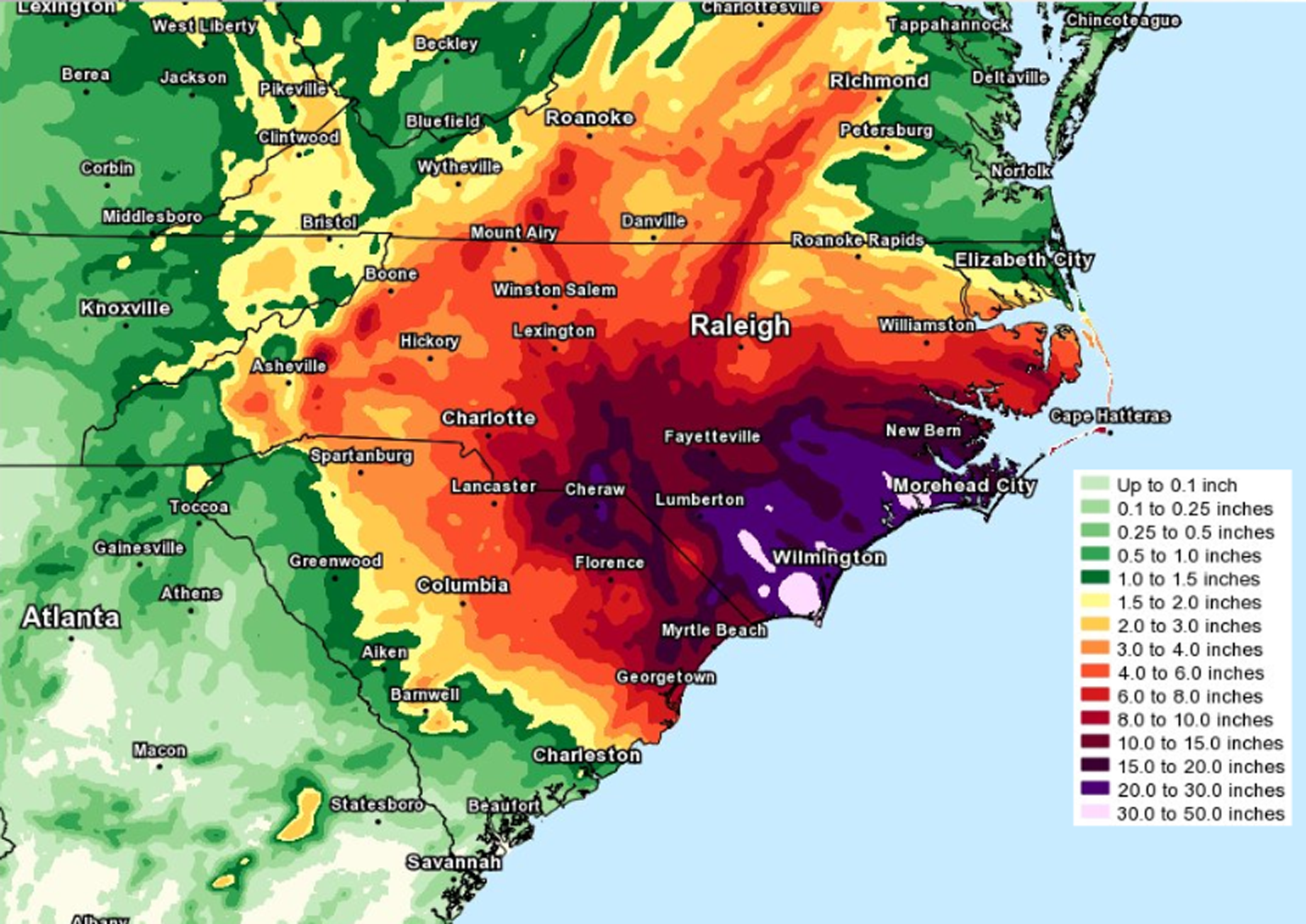

Hurricane Florence

September 2018 saw Hurricane Florence crawl across the Carolinas to set the record for wettest tropical cyclone to impact the region. Florence made landfall as a Category 1 hurricane, but its forward speed of between 3 and 6 mph ensured that its rainfall was deposited over an extremely wide area. According to preliminary reports from the National Weather Service, in North Carolina 35.93 inches fell in Elizabethtown and more than 30 inches fell on Swansboro. Many other locations received more than 20 inches. Several bodies of water rose above record levels, submerging some of the gauges used to record river levels, and widespread riverine and flash flooding occurred in North Carolina and South Carolina.

And More Recently …

September 2019’s Tropical Storm Imelda was the fifth-wettest tropical cyclone on record in the U.S. and the third slow-moving storm to impact the U.S. in as many years. It was the second-wettest storm to flood Texas, but its impact might have been even worse had it stalled, as Harvey did; instead, Imelda continued moving northward across western Louisiana, albeit slowly. The National Weather Service reported “major, catastrophic flooding” occurring across much of southeast Texas.

Besides record-breaking tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic, 2020 has been marked by a rapid succession of wet storms making landfall on the Gulf Coast, bringing wave after wave of heavy precipitation with them and leaving extensive inland flooding in their wake. Hurricane Marco fortunately weakened before it made landfall late on August 24 near the mouth of the Mississippi River as a weak tropical storm progressing at about 8 mph. Close on Marco’s heels, Hurricane Laura crossed the coast near Cameron, Louisiana, on August 27 moving at 15 mph and bringing 1-minute sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h). It deposited 5 to 10 inches of rainfall on parts of Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas and caused flash flooding in some areas.

Hurricane Sally followed on September 16, crawling ashore near Gulf Shores, Alabama at barely 3 mph as a Category 2 storm. In some areas four months’ worth of rain fell in just four days, but the heaviest rainfall was largely confined to a relatively small area covering the Florida Panhandle west of Tallahassee and southeastern Alabama. Up to 30 inches fell in Orange Beach, Alabama, and 24.8 inches in downtown Pensacola, Florida, resulting in some historic and catastrophic flooding. Not long after Sally, Tropical Storm Beta reached Texas on September 22, causing flooding throughout the state and along the Gulf Coast.

A Unified View of Flood Risk from All Sources

The past decade’s extreme precipitation events, both tropical and non-tropical, have brought to the forefront the importance of modeling flood risk outside floodplains. By leveraging innovative methodologies that realistically simulate rainfall patterns of tropical cyclones using advanced machine learning techniques, our U.S. hurricane and inland flood models are able to provide a unified view of flood risk from all sources—tropical and non-tropical precipitation on and off the floodplains and coastal storm surge—across the contiguous United States.

The AIR hurricane and inland flood models for the United States employ the same, component-level vulnerability framework to quantify losses from inland flooding and hurricane precipitation events. The same primary and secondary risk features are available and applied for both of the models. When the AIR Hurricane Model for the United States and the AIR Inland Flood Model for the United States are used in combination, they provide one unified view of precipitation hazard. These high-resolution, physically based catastrophe models can simulate both tropical and non-tropical precipitation realistically, allowing insurers to expand into new markets profitably and cover the flood insurance gap.

For more, read our AIR Current on “Modeling Hurricane-Induced Precipitation”