The U.S. is experiencing the worst outbreak of Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) in nearly 10 years, with three deaths and more than a dozen serious illnesses caused by the virus. Less than 5% of human cases are symptomatic, but in those cases death rates can reach 30–40%, and survivors often have severe neurological damage. There is no human vaccine available for EEE, and only supportive care is possible for those who fall ill.

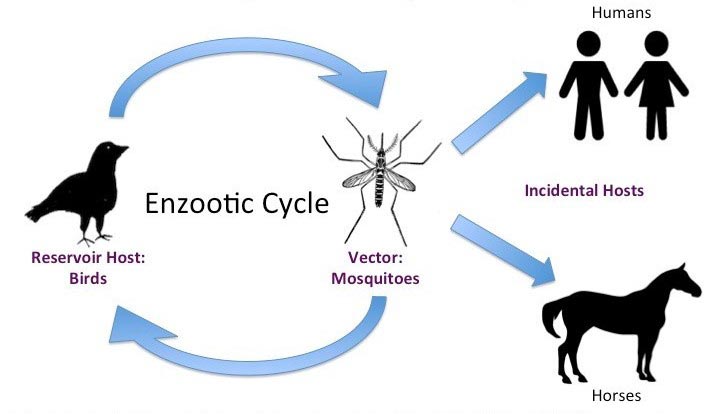

EEE virus is a mosquito-borne alphavirus found primarily in eastern states of the U.S. The virus is naturally maintained in the environment in the avian population, transmitted by the Culiseta melanura and Culiseta morsitans species of mosquitos. A different set of mosquitoes (Aedes vexans, Coquillettidia perturbans, Ochlerotatus canadensis, and Ochlerotatus sollicitans) transmits the virus to mammals such as humans, deer, horses, and other domesticated animals (i.e., goats and alpacas), which are "dead-end" hosts that cannot transmit the virus themselves. The disease is most often identified in horses; the symptomatic disease is almost universally fatal for these animals, but there is an effective vaccine for them.

Disease Monitoring

EEE reappears in cycles of roughly 10 to 20 years, with the most recent previous outbreak cycle in Massachusetts ending in 2012. Public health surveillance includes sampling horses and mosquito traps for signs of the virus. The current outbreak has already caused 14 human cases, three of which resulted in death. Deaths have been reported in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Michigan. Confirmed human cases have been reported in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Michigan, New Jersey, and North Carolina.

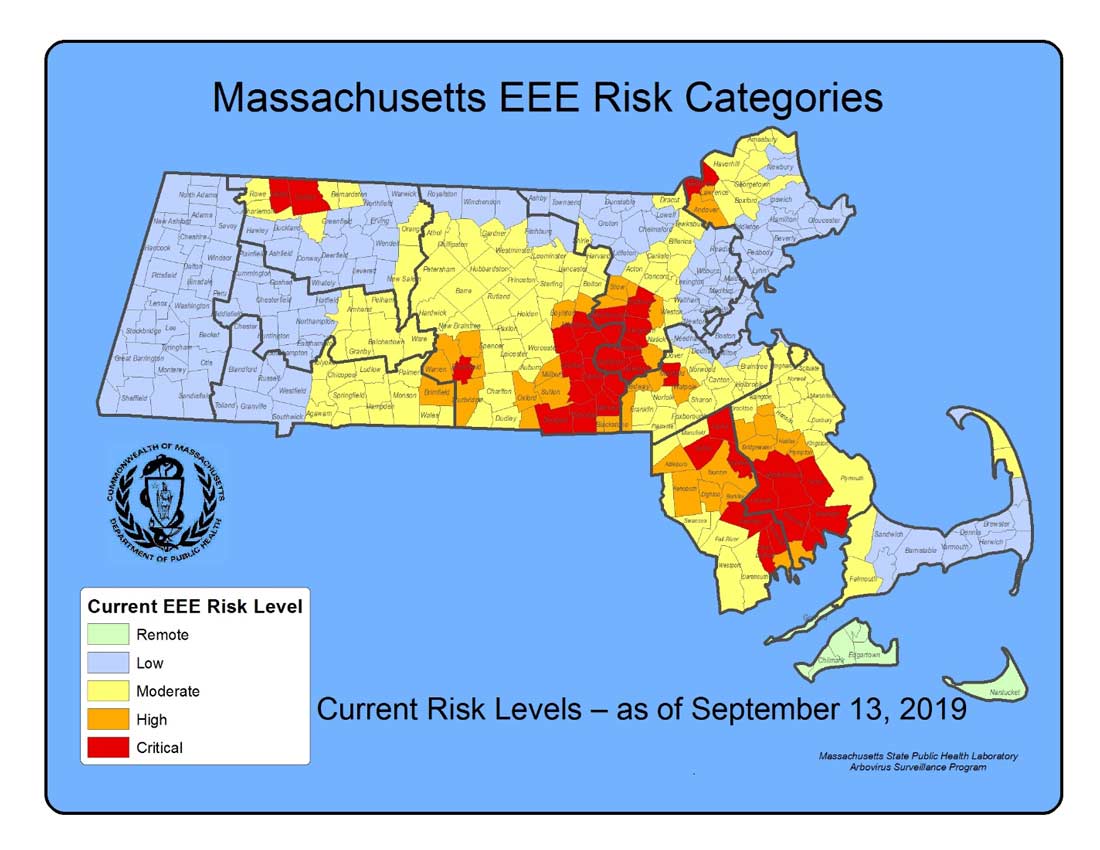

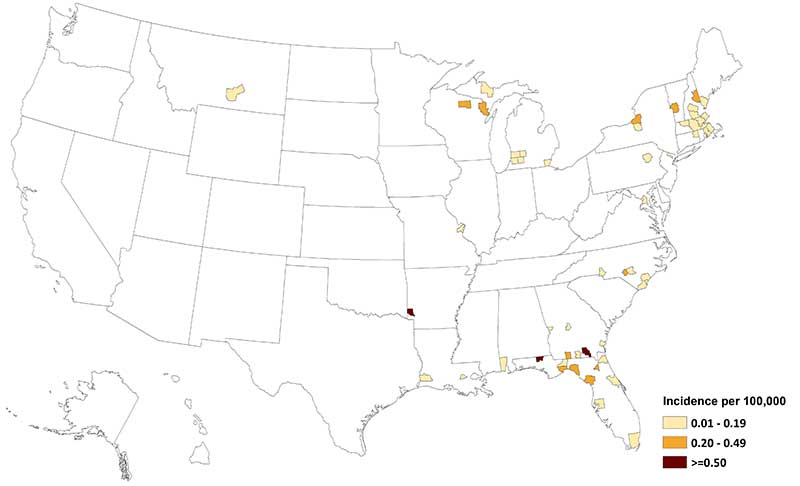

According to the CDC, the virus is present in animal hosts along the Eastern Seaboard and Gulf of Mexico (Figure 2). Most recently risk levels in Massachusetts were increased after surveillance showed animals testing positive for the disease, and risk maps by town were updated (Figure 3).

History

EEE was first identified in horses in 1831, and the virus was isolated from horses in 1933. It became known as a dangerous human disease in 1938 when an outbreak killed 30 children in the U.S. Northeast. Between 2003 and 2016, there were a total of 121 cases in the United States, with a median of eight cases per year. The highest averages were in the states of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Vermont, Maine, and Alabama. One case in Montana appears to have been travel-related, as there were no reports of the disease in animals in Montana.

Considering domestic and global catastrophic pandemic risk is a critical part of life and health insurance risk management. The AIR Vector Model, anticipated for release next year, covers global vector risks for a broad range of vector-borne diseases, excluding EEE and other viruses that cause very few deaths.

ƒfigre