The catastrophic wildfires that raced through Gatlinburg last week claimed 14 lives and nearly 1,700 homes, devastating the region and shocking residents long accustomed to the safety of this peaceful, forest idyll. As a result of an investigation into the origins of the blazes, two juveniles have now been charged with aggravated arson.

A popular tourist town just outside Great Smoky Mountains National Park in eastern Tennessee, Gatlinburg isn’t where large, devastating wildfires are expected to occur. This part of the Appalachian Mountains is considered a temperate rainforest, with wet, humid conditions that minimize the ability of wildfires to grow uncontrollably. However, many more ignitions occur annually in the southeastern U.S. than in western states, and, when combined with current drought conditions, this proved fatal for Gatlinburg.

Elevated risk

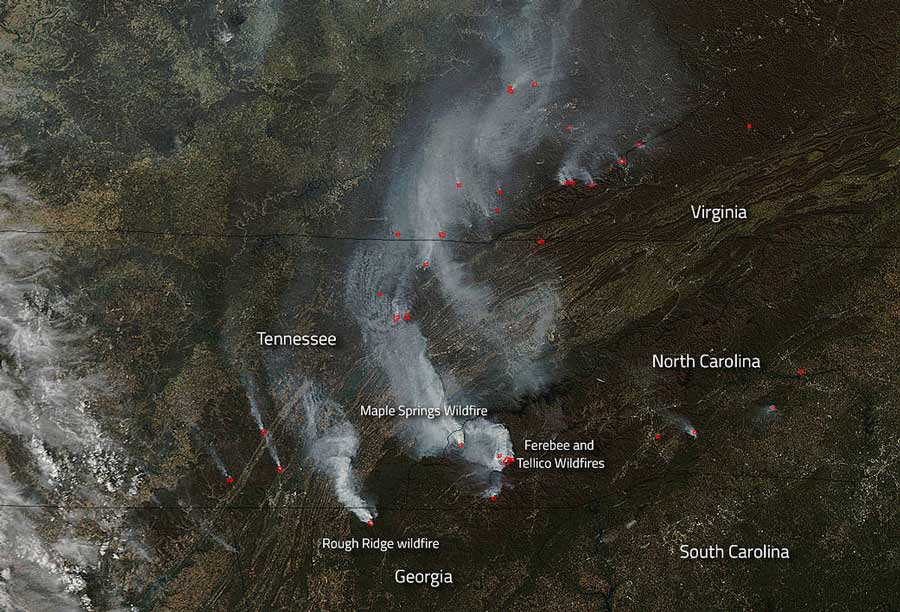

Some southern and southeastern states have been experiencing drought conditions of varying intensities this year, and eastern Tennessee was in an Extreme to Exceptional Drought by the time of the wildfire, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Long-term droughts lead to lower moisture content in wildland fuels, making them more susceptible to burning; when an ignition occurs, it is easier for the fire to grow out of control. The National Interagency Fire Center predicted an ‘Above Normal’ wildland fire potential for November with the outlook decreasing for December.

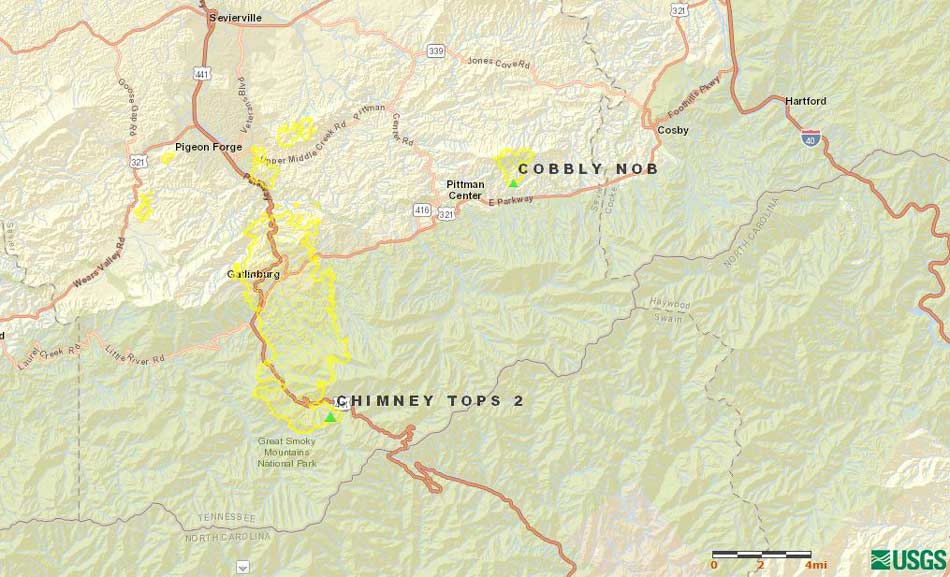

Dry fuel conditions plus high wind speeds create the perfect storm for wildfires; such winds came on November 28. The Chimney Tops 2 wildfire had been burning for five days deep within the national forest when hurricane-force winds exceeding 90 mph pushed it toward Gatlinburg and Pigeon Forge.

Fuel buildup

Although large wildfires are less common in the southeastern U.S. than the western U.S., it is important to remember that they used to be a critical part of the southeastern ecosystem. Research within Great Smoky Mountain National Park has shown this area may have had large wildfire events such as this occur as often as every 15 years. However, modern-day suppression of wildfires in the region has led to the buildup of fuels and created conditions similar to those experienced in western parks, which are much more prone to high intensity wildfire events.

While the southeastern U.S. may have on average less risk from large, catastrophic wildfires, the region’s wildfire risk cannot be ignored. Much of this area is considered to be the wildland-urban interface (WUI)— where development meets undeveloped lands and fuels are in close proximity or intermixed with exposures—a zone of transition most at risk from wildfires.

Underestimating the risk

In some ways, not being in a fire-prone area may have compromised the ability of the town to effectively respond to the wildfire threat. The City of Gatlinburg wasn’t designed to minimize the impact of wildfires. Situated to be a picturesque city nestled in the mountains, it has only a few roads leading in and out. Many of the residential roads in the city are winding mountain roads, which impede access in an emergency. Southeastern Tennessee isn’t usually at risk from wildfires, so the more common preventive measures used in the western U.S. to minimize the risk of property damage, such as increased setback distance and the use of fire-resistant building materials, were not in place. Homes are often traditional, large, wooden structures that match the forested hillside, and they can become fuel if a wildfire moves through the area.

As access to the city is restored and the total damage is surveyed, we will undoubtedly learn many lessons from the wildfire that scorched Gatlinburg. Emergency planning and preparedness are key lessons to learn, but understanding your vulnerability to and the potential for catastrophic risks before these tragedies occur is the best means to lessening the impact of such events in the future.