Earthquakes in New South Wales, Australia, are generally weak and infrequent—but on occasion they can cause significant losses. Thirty years ago this month, for example, a temblor of M5.6 was Australia’s most damaging seismic event in recent times. The earthquake struck near the town of Boolaroo, 15 kilometers west of Newcastle’s central business district and about 69 miles (111 km) north-northeast of Sydney on December 28, 1989.

Damage to buildings, facilities, and infrastructure was reported over an area of 9,000 km. The central business district in Newcastle and the nearby suburb of Hamilton suffered extensive damage; buildings as far away as Sydney suffered minor damage. In total, the event damaged more than 60,000 buildings and claimed the lives of 13 people.

The quake generated AUD 862 million in insured losses (1989 AUD) according to the Insurance Council of Australia.

What Lies Beneath the Surface

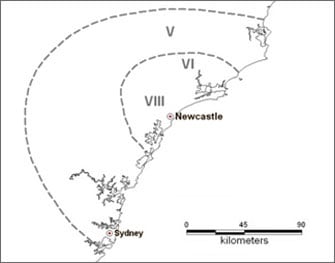

The Newcastle quake occurred below the Sydney Basin, a complex intraplate environment bordering the Newcastle Dome Basin Belt to the north and the Hunter Mooki Thrust to the east. The concentration of damage was located at sites with poor soil conditions, principally areas with unconsolidated sediments and rocky materials covering bedrock, where shaking intensity was amplified by as much as four times that of firm soil sites. The isoseismal map in Figure 1 shows the distribution of Modified Mercalli intensity scale values. A maximum intensity of VIII was felt in pockets across a radius of roughly 80 kilometers, and swaying was reported in high-rise buildings in Melbourne, some 800 kilometers away.

Why Buildings Suffered Major Damage

Most of Australia is sparsely settled and the bulk of exposures are in its major cities and suburbs. New South Wales has the highest population density of any Australian state and includes the major cities of Newcastle and Sydney—Australia’s largest city. Because Australia is relatively stable tectonically and few intense earthquakes occurred in more densely populated areas until the second half of the 20th century, not much attention was paid to establishing or following building codes and construction standards.

The majority of buildings that suffered major damage in 1989 were constructed of unreinforced masonry (URM), a building type known for its lack of lateral resisting system. Building inspections performed immediately after the earthquake revealed extensive evidence of structural deterioration, primarily in older buildings that dated from the late 1800s and early 1900s. However, even some modern buildings, including the Pasminco zinc refinery, the John Hunter Hospital (which had not yet opened), and the Newcastle Technical College experienced structural failure. This highlights the fact that even modern construction may be at risk when non-ductile elements are used on soft soil conditions.

Hazard Maps and Building Codes

Prior to the Newcastle earthquake it had been widely assumed that earthquakes posed little threat to urban communities in Australia and that moderate-sized earthquakes would not lead to loss of life or significant physical damage. Soon after the Newcastle earthquake, the first Australian probabilistic hazard assessment was completed in 1990. It was quickly followed by the creation of a National Seismic Hazard Map of Australia in 1991 to form the basis for the Australian building code (AS1170-4).

At that time Australia’s location in the middle of a tectonic plate, not on an active boundary like the “Ring of Fire,” suggested a higher level of hazard than other stable continental regions. That view has now changed.

Geoscience Australia (GA) has developed an updated National Seismic Hazard Map for a revised building code (AS1170.4-2018). Thanks to the revision of historical earthquake catalog data and a change in ground motion model this latest hazard map challenges established conceptions of Australia’s seismic hazard and generally decreases seismic hazard factors significantly. The findings of the NSHA18 project are so significant that an updated AIR Earthquake Model for Australia is anticipated for release in the summer (winter in the Southern Hemisphere).

What hasn’t changed, however, is the nature of the risk. Sydney—the cultural and economic hub of the country—is not far from Newcastle, and experiences similar earthquake risk. Much of Sydney’s building stock is constructed of URM, which is highly susceptible to earthquake damage. Is this another catastrophe waiting to happen?

What the New View of Seismic Hazard in Australia Means: Read the blog.