What the 1918 Flu Pandemic Can Teach Today's Insurers

Mar 29, 2018

Editor's Note: On the 100th anniversary of the “Spanish flu,” we examine why this historic pandemic was so devastating, show potential impacts of a modern Spanish flu pandemic in AIR’s modeled scenario, and provide insights for today’s insurers on how they can better prepare for such an event.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the 1918 influenza (flu) pandemic, which was associated with an estimated 20 to 100 million deaths worldwide at a time when the global population was approximately 1.8 billion. It was among the deadliest public health crises in human history.

The outbreak’s origin was likely in or near Fort Riley, Kansas, where the first case was reported on March 11, 1918. On the same date, more than 100 soldiers went to the camp infirmary with a fever. Within a week, several dozen people had died. Interestingly, the official cause of death was not the viral infection but bacterial pneumonia.

What became known as the “Spanish flu” pandemic had three waves: spring of 1918, fall of 1918, and early 1919. The second wave was the most aggressive. Eventually, about one-quarter of the United States’ and one-fifth of the world’s population would become infected.1 AIR estimates that if the 1918 flu pandemic were to recur today, U.S. life insurance companies would pay out roughly USD 20 billion in benefits.

Highly Virulent and Transmissible Strain Attacked the Young and Healthy

There were a few factors that made the 1918 flu different from other pandemics of the past century (1957, 1968, and 2009). Compared to other flu viruses, the virus that caused the 1918 pandemic was highly transmissible. It is estimated that the attack rate—the proportion of persons exposed to the disease who become ill—was around 30%.

The 1918 flu pandemic also had a higher case fatality ratio (CFR) compared to other flu pandemics of the last century. It is estimated that the CFR for the 1918 pandemic was between 2 and 5%, which is at least 10 times higher than the CFR for a typical seasonal flu.

Unlike other flu pandemics, the 1918 Spanish flu mortality rate for young adults (25 to 40 years old) was exceptionally high. Usually influenza puts the very young and/or the very old at higher risk compared to the other age groups, making the CFR profile “U” or “J” shaped. However, the 1918 flu CFR had a “W” shaped profile (see Figure 1), which reflects a significant increase in mortality among healthy working adults. It is still not clear why. A contributing factor may have been the high virulence of the disease, which triggered a "cytokine storm"—an overreaction of the immune system that often leads to pneumonia and death in certain victims by suppressing the body's antiviral responses and promoting increased inflammation. Young, healthy adults are more likely than other age groups to suffer a cytokine storm because their immune systems are robust and, therefore, more prone to overreaction. An alternative explanation for the lower CFR profile in the 40- to 60-year-old age group could be their previous exposure to the H1N1 virus during the 1889 pandemic, granting them higher levels of prior antibodies.

Evidence suggests World War I also played an important role in increasing the spread and fatality of the 1918 flu pandemic. Troops living in close quarters, along with mass movements by land and sea, likely increased the spread of the disease. The limited healthcare available because of the diverted attention of medical staff to the war effort likely exacerbated the effects of the pandemic. Finally, many countries censored news reports about the pandemic to keep up morale as the war drew to a close; unfortunately, this censorship prevented people from knowing the severity and extent of the pandemic so that they could take precautions. In fact, this pandemic gained the name “Spanish flu” in the United States and Europe because Spain was neutral during the war, so the Spanish media was freely reporting on the outbreak, leading to misunderstandings about the origin of the disease.

Modeling a Modern-Day Spanish Flu

To estimate the effects of a modern-day 1918 pandemic, the AIR Pandemic Model was run for a range of events using initial parameters consistent with the historical pandemic, while also considering certain changes in medical knowledge and practice, as well as transportation, since 1918. The pandemic was then propagated through the model to estimate mortality and life insurance losses, revealing much about the impact of those changes.

AIR considered several factors in modeling a modern flu pandemic to more accurately evaluate the impact on the overall mortality and morbidity. Although the developments in treatment and availability of vaccination, as well as global air travel and local commute factors, were adjusted to modern day, the biological characteristics of the flu pandemic were assumed to be similar to the 1918 flu. The reproduction number selected for these scenarios was between 1.8 and 2.48 (meaning that for every person with the flu 1.8 to 2.48 new people become infected with it in a susceptible population) to keep it similar to the estimated values for the 1918 pandemic. However, the CFR values were adjusted based on advancements in medical technologies, treatment, and pandemic preparedness.

The start location for this pandemic was assumed to be in Kansas in the U.S. From the animation in Figure 2, we can observe that one of the main contributors to the increase in the speed of global spread of flu is the modern high rate of air travel. We used the rate of air travel between airports, along with daily local commuting, to consider realistic possibilities of disease transmission.

Figure 2. Modeled spread of a recurrence of the 1918 flu pandemic, highlighting where airline flights help the initial spread of the pandemic to new regions. (Source: AIR)Applying the currently available pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions in our model, our analysis showed that for an influenza pandemic it takes about six months from when the World Health Organization declares an outbreak to develop a vaccine and distribute it globally. The efficacy of the applied vaccine is assumed to be age-dependent, with a range of 40% to 60%. However, in our model, antimicrobials and antivirals can be immediately prescribed to infected individuals to decrease the probability of transmission and reduce the chance of mortality due to the complications associated with influenza, such as pneumonia. The model also considers how the availability of both vaccines and antivirals varies according to each modeled country's stockpile size, resource levels, and distribution capabilities.

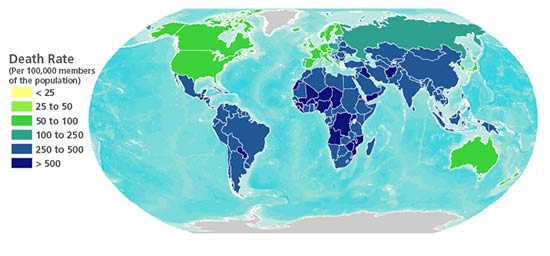

The results of AIR stochastic modeling show that a modern day Spanish flu would cause between 21 and 33 million deaths worldwide. Figure 3 shows the median mortality rate for countries in this scenario.

Due to modern medical advancements, the results of the AIR model show a nearly 90% reduction in the case fatality rate in modern Spanish Flu compared to what was observed in 1918. On the other hand, an increase in the scale and frequency of air travel and an increase in the average age of the population are modern factors that increase the mortality rate by 30% and 8%, respectively, compared to the actual mortality in 1918. Taken together, these modeling results suggest that dramatically fewer deaths—nearly 70% fewer, proportionally, than occurred in 1918—would result from a Spanish flu event today.

Based on our model analysis, AIR estimates losses of between USD 15.3 and 27.8 billion for insurance companies in the United States alone. According to the American Council of Life Insurers, benefits paid to beneficiaries in 2010 amounted to more than USD 58 billion. Therefore, losses from a modern-day Spanish flu would represent close to a 48% increase in the total benefits paid by the life insurance industry.

While the AIR Pandemic Model estimates that a modern-day Spanish flu pandemic would have a less dramatic impact in terms of mortality rates than the actual Spanish flu pandemic did in 1918, it should be noted that this modeled pandemic does not represent a worst-case scenario for pandemic losses. For example, an emergent pandemic strain could be resistant to antiviral drugs; there could be manufacturing difficulties inhibiting production of a vaccine in a timely fashion; or populations in areas affected by other catastrophes could be limited in their access to treatments.

Medical and Public Health Interventions Since 1918

In 2009—91 years after the deadly 1918 pandemic—a pandemic of a novel influenza virus, H1N1, claimed between 200,000 and 500,000 lives globally. It is often said that there is little role for early pandemic detection and early public health intervention, but the 2009 flu pandemic showed the importance of a swift response. Although with the high volume of air travel, global spread of a flu pandemic could have proceeded rapidly and been impossible to control, the 2009 pandemic was neither as explosive nor as fatal as many earlier pandemics. There are many reasons for this dramatic improvement.

Studies have shown that bacterial pneumonia played a central role in most deaths in the 1918 flu pandemic. Wide availability of antibiotics after 1942 reduced the mortality of community-acquired pneumonia from 30–40% to approximately 15%. Since that time, severely ill patients and those with respiratory complications have been able to take antibiotics that treat infectious complications of flu and mitigate bacterial pneumonia. In addition, the advent of modern intensive care units and mechanical ventilation have revolutionized supportive care for patients in danger of respiratory failure—another complication of flu. Continuous cardiac monitoring and pharmaceutical advances are among the other factors that have changed significantly since 1918 and played important roles in preventing flu-associated mortality.2 However, emergence of antimicrobial resistance during the last decades has reduced the speed of success in treating patients with antivirals and antibiotics.

Aside from medical technology, public health is more advanced than in 1918, with better medical and scientific knowledge about prevention, continuous flu surveillance, more trained medical and public health personnel, established prevention programs featuring annual vaccination, and international prevention infrastructure.

Impact on Today’s Insurance Industry

Even with today’s technology, a modern severe pandemic would cause substantive direct financial losses to the insurance community. In addition, indirect losses would be severe, most notably on the asset side of the balance sheet. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the macroeconomic effect of a severe influenza pandemic similar to the 1918 Spanish flu to be a loss of 4.25% of GDP. For reference, during the Great Recession, the U.S. economy contracted by approximately 3%. This level of substantive decline would likely have an impact on the financial markets and bottom lines of individual corporations, particularly businesses reliant on consumer spending in places where people congregate, such as restaurants and shopping districts. This loss could ripple through the financial markets, impacting equity, bond, and commodity markets. Compared to their counterparts in health or property and casualty, life insurers are often more exposed to market forces, with investments in more long-term and riskier asset classes.

A flu pandemic causes a marked increase in life insurance claim expenses due to the increase in mortality of policyholders. These losses may be offset in the long term, as annuity portfolios would also experience excess mortality, reducing both liabilities and expenses in the coming years. However, this balance of risk with annuities may be only of minor benefit, as a flu pandemic would not likely hit all demographics proportionate to their general mortality. It is likely there would be a greater relative risk to the working demographic than the older demographic. In addition, many carriers specialize in life insurance or annuities, and therefore the offset could be varied based on the size of the annuity portfolio compared to the life portfolio.

One factor that may help insurance companies prepare for such an event is gaining a better understanding of the differences between the general population and their insureds in terms of age distribution and prevalence of chronic diseases as predictors of mortality rates. A more comprehensive understanding of risk can inform a range of planning decisions, such as building and maintaining accurate reserves.

Building Resilience to Future Pandemics

The major issues that have been raised by public health officials and need to be addressed are: inadequate pandemic warning systems, delay in vaccine development, and movement of a virus from animals to humans that make it difficult to deal with the virus.

With the availability of rapid antigen testing for influenza and imaging and laboratory data, the most difficult challenge today is not pandemic detection or medical knowledge about treatment and prevention. Today’s challenges include medical capacity, resource optimization, and public health and community crisis response to an event that infects up to half the population within a few weeks.

Due to concerns raised about H5N1, H3N2, and H7N9, pandemic preparedness agencies stockpiled vaccines, antivirals, and antibiotics and increased the surge capacity of hospitals and emergency medical facilities. However, most of the world does not have access to the same level of prevention and medical care as developed countries and thus can be expected to bear the greatest burden of any flu pandemic. (Read more about this topic in the blog post, “A Pandemic Facility to Protect the Poorest Countries.)

One century later, mysteries still surround the 1918 flu pandemic and it stands as a reminder not only of the importance of continuing the fight against emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, but also of what we have yet to learn about pandemics.

The next decade should yield significant advances in fundamental knowledge about pandemics and, more importantly, in prevention and control.

References

1 Stanford University, “The Influenza Pandemic of 1918”.

2 While all of these treatments are available in developed countries, their availability in other parts of the world varies

Narges Dorratoltaj, Ph.D.

Narges Dorratoltaj, Ph.D. Doug Fullam, ASA

Doug Fullam, ASA