U.S. Flood Insurance—the NFIP and Beyond

Aug 22, 2013

Editor's Note: AIR's Inland Flood Model for the United States will be released next summer. In this article—the first in a series—Raulina Wojtkiewicz, John Rollins, and Virginia Foley discuss some of the issues facing the U.S. flood insurance market today, including recent developments with the NFIP. Look for additional articles about the forthcoming U.S. flood model in the months ahead.

Flood Risk in the U.S.

Flooding causes more property damage in the United States than any other natural disaster. Following several destructive hurricanes and associated storm surge events in the 1960s, many insurers ceased covering residential flood risk in the U.S. Without the tools to accurately quantify and price the risk, insurers have been unable to offer flood insurance at "affordable" rates to the public. As a result, government-sponsored flood insurance comprises the majority of the residential market.

In 1968, Congress established the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) to address the shortfall in the availability of affordable flood coverage. From its inception, the NFIP has been managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and guided by three main mandates: to provide residential and commercial insurance coverage for flood damage, to improve floodplain management, and to develop maps of flood hazard zones.

Under the NFIP, flood insurance that could not be affordably purchased in the private marketplace is made available to home and business owners in more than 20,000 communities across the country. In exchange, participating communities agree to adopt and enforce mitigation procedures and ordinances that reduce flood risk. The program currently insures about 5.5 million homes (the majority of which are in Texas, Florida, and Louisiana) and generated $3.6 billion in premiums in 2012.1

While AIR has been modeling coastal storm surge as part of the U.S. hurricane model for more than two decades, AIR will be introducing a new inland flood model for the U.S. in 2014. The state-of-the-art model will feature a stochastic, event-based catalog, a robust financial model, and the ability to test historical scenarios and alternative construction and mitigation features. This article will examine the current state of the NFIP and how AIR's probabilistic model answers the call of many stakeholders for a comprehensive and reliable approach to assessing inland flood risk.

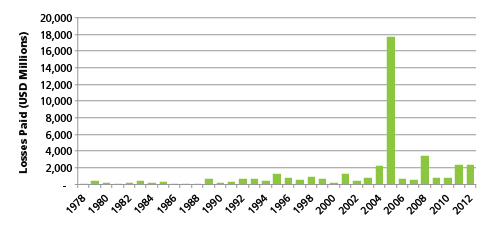

The NFIP Business Model

Contrary to required practices in the insurance industry, Congress allowed the NFIP to operate without any reserves, or surplus, to absorb or transfer the risk of severe flood events. Instead, it was expected to collect just enough in annual premiums to cover administrative costs and historical average annual losses. This led to rates far below actuarially sound levels, even for properties that were not "grandfathered" or offered a special subsidy. However, the flaw was concealed, in part, because the early years of the program largely coincided with a multi-decadal period of relatively inactive hurricane seasons. Then hurricanes Katrina and Rita struck, putting the program $18 billion in debt, and the NFIP borrowed the shortfall from the U.S. Treasury. In 2012, Superstorm Sandy made matters worse, and in January 2013, Congress increased the borrowing authority of the NFIP from $20.775 billion to $30.425 billion.

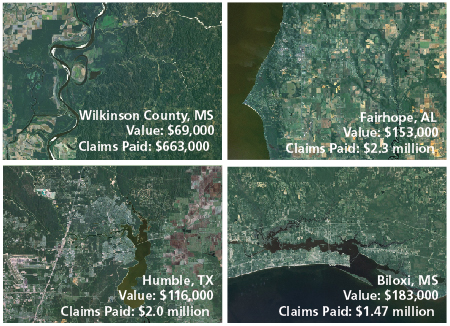

Sandy served to re-emphasize that the program was not actuarially sound and in need of significant reform. Among the chief grievances are that the FEMA Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRM)—used in determining NFIP premium rates—are outdated in many communities. Perhaps the toughest criticism of the NFIP is that the same insured and subsidized properties are flooded repeatedly and are rebuilt, sometimes several times, in the same location using NFIP funds. As of 2012, repeat property losses account for just 1% of NFIP's insured properties, but 25% to 30% of claims.2 Put another way, one in 10 policies has a claims history more than the value of the property.

A 2011 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) highlighted the lack of an effective system to manage basic policy and claims data. The GAO called for greater use of risk-based premiums, authorizing the program to account for long-term flood erosion on floodplain maps and increasing FEMA's ability to charge more or deny coverage for repetitive loss properties.

After numerous stopgap extensions and two temporary shutdowns for several weeks, Congress approved a five-year extension of the NFIP in 2012, called the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012.4 The act overhauled many aspects of the program, removing a variety of existing premium subsidies, mandating improved flood mapping, introducing the gradual phase-in of risk-based rates for remapped properties, and increasing the annual cap on rate increases from 10% to 20%. In addition, it allows FEMA to purchase reinsurance cover for catastrophic losses, and requires several reports to Congress on the program's claims-paying ability and the feasibility of reinsurance and privatization.

Opportunities for the Private Market

While the NFIP has been the dominant player in the flood insurance market, there are long-term opportunities for private insurers and gaps to fill. Private insurers may offer superior performance in building a surplus, underwriting properties, spreading risk through the reinsurance and capital markets, determining actuarially sound rates, and prioritizing and implementing coastal mitigation strategies. Furthermore, insurers that are currently managing exposure to flood should be prepared for the possibility of a partial or full privatization of the NFIP, an idea that has garnered increased attention since Sandy. In theory, there is nothing preventing insurers from entering the flood insurance market, except the prospect of competing with artificially low premiums offered by the government.

In 1983, private insurers began to participate in the Write Your Own Program (WYO), which allows property/casualty insurance companies to write and service policies in their own names, with the risk fully backed by the NFIP. Participants receive a flat percentage commission for acquisition and servicing expenses, while the NFIP benefits from the regional expertise of insurers in flood-prone areas.

Going forward, increased participation by the private market will largely depend on the ability to manage accumulations of exposure in flood-prone regions and reliably assess flood risk.

Probabilistic Modeling and the Way Ahead

The actuarial approach mandated for NFIP in 1968—dependent solely on historical claims data—suffers from the same flaws as those used by private insurers for hurricane and earthquake perils prior to the widespread adoption of catastrophe modeling. It is now well understood in the private sector that historical loss data is insufficient for ratemaking for catastrophic perils. Proper consideration of the changing landscape of insured properties, advancements in geographic risk classification, and detailed data on construction practices and materials requires an integrated catastrophe modeling approach to generate the appropriate inputs to calculate actuarially sound rates.

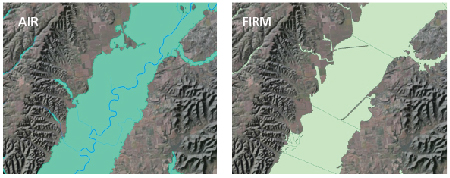

Next year AIR will release a fully probabilistic flood model that captures the complexities inherent in formulating an objective, risk-based understanding of flood risk. The model features a robust, event-based catalog developed using advanced weather simulation techniques, and it uses high-resolution terrain information to estimate flood depths, the critical factor in estimating damage. The model also accounts for the possible failure of flood defenses, meaning that unlike in FIRM maps, AIR considers the area behind levees to be at risk from flooding. And because roughly 30% of NFIP flood insurance claims come from properties outside of the 100- year floodplain, AIR has developed a separate module for off-floodplain loss estimation. Damage and losses can be aggregated, and the model will allow for the application of a wide variety of policy terms.

Closing Thoughts

After more than 40 years of operation, the NFIP is one of the longest standing government-run disaster insurance programs in the world, but its recent financial troubles have exposed fundamental flaws in its design. Change may be coming to the marketplace for flood insurance. Insurers and other stakeholders should develop centers of excellence in managing flood risk to position themselves in the new ecosystem. Quite simply, AIR will answer the needs of both the insurance industry and government for more detailed flood modeling.

Our role is to apply the same globally respected and robust simulation architecture inherent in all of our models to the new challenge of U.S. inland flood. AIR's model is designed to meet the wide spectrum of flood risk management needs of the insurance industry. By modeling the effects of precipitation-induced flooding to properties both on and off the floodplain, it will enable insurers to make more informed underwriting and pricing decisions and develop more effective portfolio management, risk financing, and risk management strategies. We are looking forward to delivering this new level of expertise and functionality to the marketplace next year.

1 http://www.fema.gov/statistics-calendar-year

2 United States Government Accountability Office, Flood Insurance Public Policy Goals Provide a Framework for Reform (http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d11670t.pdf)

3 http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2010-08-25-flood-insurance_N.html

4Passed as part of HR 4348, an omnibus transportation bill.

By: Raulina Wojtkiewicz

By: Raulina Wojtkiewicz By: John Rollins, FCAS, MAAA

By: John Rollins, FCAS, MAAA By: Virginia Foley

By: Virginia Foley