An “outbreak,” like an epidemic, is an increase in the number of cases of a disease above the normal level, but the term is usually applied to a more limited geographic area. When diseases like Zika, HIV, and Ebola hit the headlines, they often bring to mind dramatic epidemics of novel disease agents sweeping through regions where the population has no natural defenses against them. However, most outbreaks are of known diseases—even preventable ones such as measles or pertussis—which still tend to affect the portion of the population that has no natural defenses.

Basic sanitation, such as clean water, and public health infrastructure keep dense populations—which would otherwise be perfect breeding grounds for outbreaks—safe from these events. But what happens when that infrastructure breaks down, even temporarily? The results may not surprise you, but the extent to which they are behind outbreaks might. Table 1 summarizes some categories of catastrophic events and their associated level of disease risk, by broad type.

| DISASTER TYPE | PERSON-TO-PERSON* | WATER-BORNE** | FOOD-BORNE*** |

|---|---|---|---|

|

* Shigellosis, streptococcal skin infections, scabies, infectious hepatitis, pertussis, measles, diphtheria, other respiratory infections, giardiasis, HIV/AIDS, other sexually transmitted diseases, meningococcal disease, plague. ** Typhoid and paratyphoid fevers, cholera, leptospirosis, infectious hepatitis, shigellosis, campylobacter, salmonella, E. coli, cryptosporidiosis. *** Typhoid and paratyphoid fevers, cholera, infectious hepatitis, shigellosis, campylobacter, salmonella, E. coli, amebiasis, giardiasis, cryptosporidium. |

|||

| Volcano | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Earthquake | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Hurricane | Medium | High | Medium |

| Tornado | Low | Low | Low |

| Heat Wave | Low | Low | Low |

| Cold Wave | Low | Low | Low |

| Flood | Medium | High | Medium |

| Famine | High | High | Medium |

| Air Pollution | Low | Low | Low |

| Industrial Accident | Low | Low | Low |

| Fire | Low | Low | Low |

| Radiation | Low | Low | Low |

| Civil War/Refugees | High | High | High |

In general, the more extensive the damage caused by a catastrophe and the greater the population displacement, the more likely a disease is to spread. There are many different combinations of events, event severities, endemic diseases, and levels of development that influence the probability of disease outbreaks after an event. Catastrophes facilitate disease dispersion in many specific ways, including:

- Population displacement

- Crowding in shelters/camps, increasing contact between people

- Mixing of different regional populations with different levels of vaccination or endemic disease

- Flooding

- Contamination of drinking water

- Spread of infectious mud or soils (leptospirosis)

- Public health infrastructure breakdown

- Disruption or delay of vaccination programs

- Death or disappearance of key medical and administrative staff

- Destruction of key facilities (laboratories, hospitals, clinics, etc.)

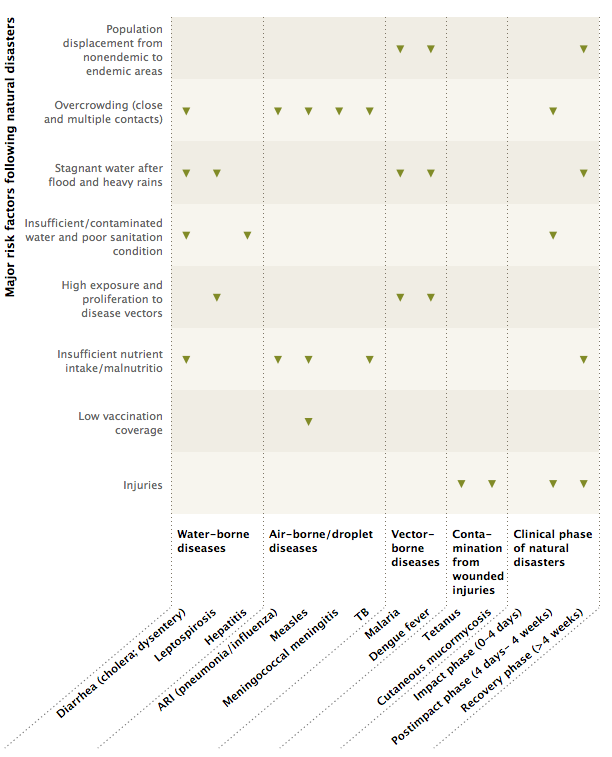

Table 2 shows more specific risk factors and the clinical phase of the event in which these diseases appear and spread.

Diseases spread by contaminated water or soils distributed by flooding can significantly impact catastrophe survivors as contagions may be passed to them through drinking water or water exposure, for example. As far as airborne diseases are concerned, the primary threats are measles, flu, meningitis, and tuberculosis. Measles is a vaccine-preventable disease, but it is extremely infectious among the unvaccinated, and high rates of vaccination are required to protect a population. In crowded shelters, vaccination rates need to be even higher to prevent the spread of measles; when a population has been displaced for a longer period of time, vaccination schedules can be disrupted, leading to periodic outbreaks, especially in children who are either unvaccinated or improperly vaccinated.

In summary, catastrophes can facilitate disease outbreaks by damaging key infrastructure, displacing people, and especially disrupting the function of vital health services. The magnitude of the event determines the extent of the damage, displacement, and disruption, and influences the probability of a post-cat disease outbreak, increasing mortality and morbidity as well as the expense of response. Appropriate responses can reduce the size, duration, and geographical dimensions of these types of outbreaks.

For more information on how AIR captures inherent uncertainty of disease spread, view our Life & Health page.

Read AIR’s extreme scenario analysis, Global Pandemic Megadisaster—Are You Prepared?