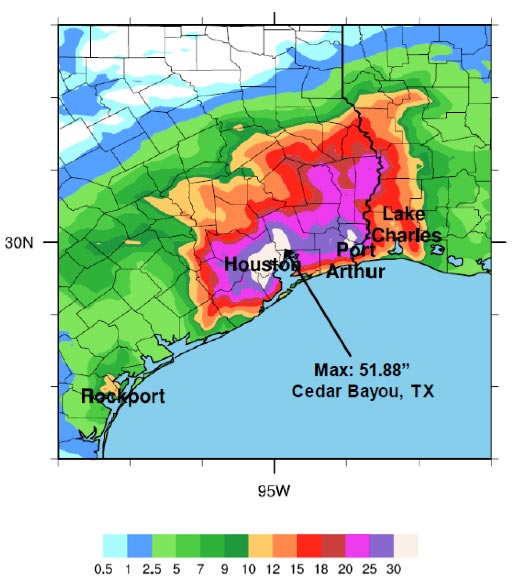

As Peter Sousounis noted in his blog, Hurricane Harvey will be remembered for its record breaking rainfall and flooding. Hurricane Harvey made its first landfall as a Category 4 hurricane on Friday, August 24, wandered northwesterly while weakening to a tropical storm, and got stalled by day’s end on August 25 some 50 miles southeast of the San Antonio region. Throughout Saturday and Sunday, feeder bands aided by the deep and plentiful moisture of the Gulf of Mexico, circulated cyclonically around the center of the system, particularly to the north and east of the center of low pressure, affecting areas from Houston to Beaumont. With little movement of the system, the heavy rain bands persisted over the Houston area through Monday with training bands leading to a widespread 20-40” accumulation across the region. The National Weather Service office in Houston officially recorded 43.38”.

Harvey has rewritten the record books for rainfall totals for many locales across the state of Texas, as well as the continental United States. To begin with, the most ever rainfall recorded from a tropical cyclone for a single location occurred in Cedar Bayou, Texas, was 51.88 inches, easily surpassing the states (and continental) prior record of 48 inches in Medina, Texas, from Tropical Storm Amelia in 1978. Moreover, the three day maximum for major cities in the continental U.S. was broken at Houston Hobby Airport (32.47 inches) with third place also residing from Harvey’s path (Houston Intercontinental Airport-28.44 inches). As of Wednesday, more than five stations across southeastern Texas had surpassed 45 inches of rainfall, including the 48 inches that has fallen in Beaumont Texas in the five day period.

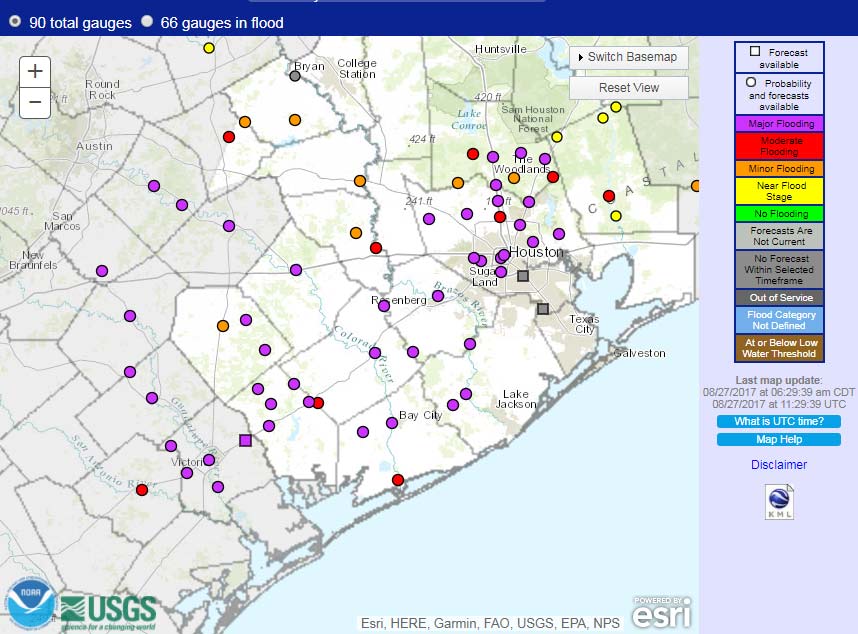

As a result of the unprecedented rainfall that fell in the Houston and its surrounding areas, 66 of the 120 National Weather Service river gauging stations in the Houston and Galveston areas were in various stages of flooding during the event. Several river gauges experienced major flood stages and crested with new record setting flood levels. For example, Buffalo Bayou that flows through the Houston downtown area crested at 63.5 feet, more than two feet higher than the previous record of 61.2 feet set in 1992. Similarly, the Cypress Creek flowing through neighborhoods north of Houston downtown crested about 3 feet higher than the previous record of 94.3 feet set in 1949. Flood levels corresponded to astounding 100-, 200-, and 750-year return periods for river water level stages on Cypress Creek near Westfield, Greens Bayou near Houston, and on West Fork San Jacinto River near Porter, Texas.

While Houston is well-known as the only major city in North America without zoning, it does have land-use regulations. Nevertheless, it has seen extensive development over the last half century, and a large percentage of impervious surfaces can increase an area’s runoff coefficient significantly. According to Rice University hydrologist Phil Bedient, for example, rainfall in the Brays Bayou watershed in southwest Harris County has increased by 26% during the past four decades, but runoff has grown 204%. Houston is also one of the flattest major metropolitan areas in the U.S. Its drainage systems consist largely of natural bayous and more than 2,500 miles of man-made channels with only a gentle gradient from west to east with which to move water out of the city to Galveston Bay.

The massive amount of precipitation that fell on the region over a five day period had to go somewhere; unfortunately, unable to drain or soak away quickly enough, it inundated the city. No place can be expected to cope effectively with the amount of rainfall that Houston experienced, but clearly the city is going to have to invest in its drainage infrastructure, discourage building within the 100-year floodplain, and enhance its natural capacity to absorb rainwater if it is to fare better during its next 500-year flood event.

Read the AIR Current: Build It and They Will Come: The Role of Land Development in Natural Disasters