Hurricane Dorian has etched its name permanently into the annals of Bahamian history. While Florida was fortunate to escape the fury of a potential multi-billion-dollar event, the Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama Island in the northern part of this picturesque island nation experienced Category 5 winds and coastal storm surge that shredded homes and submerged vehicles and boats. It was an epic disaster on an unprecedented scale for the northern Bahamas (Figure 1).

It is impossible to quantify the toll Dorian has had and will have on the people who survived it. But as structural engineers, we try to quantify what we can to make some sense of natural disasters. We tend to look at catastrophic events through our engineering lens to glean what lessons we can about an event’s impact on the built environment for future applications. In this post we will discuss the building stock, or exposure, in the Bahamas where Dorian had the greatest impact and the role the country’s building codes played.

Bahamas Building Stock

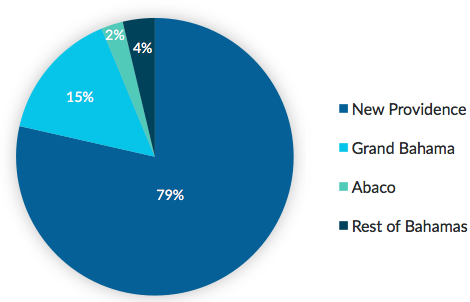

The Bahamas comprises about 700 islands and cays, but only a few dozen are inhabited. The largest in area, Andros, has a small population of 7,000 to 8,000 and lies south of the track Dorian took. New Providence has a population of more than 270,000 and is where the capital and the largest city, Nassau, is located; this island not surprisingly accounts for the lion’s share of Bahama’s exposures (79%). New Providence escaped a direct hit by Dorian. The next largest in terms of exposure is Grand Bahama, with a population of more than 50,000, where the second largest city, Freeport, is located. The Abaco Islands, which include Marsh Harbour, the third largest city with a population of more than 6,000 is the next largest in terms of exposure. Grand Bahama and Abaco together total approximately 17% of the country’s insured exposure. Figure 2 shows the distribution of insured exposures across residential, commercial, and automobile lines in the Bahamas.

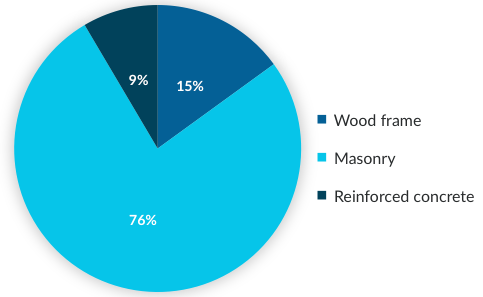

The distribution of various construction classes among residential buildings in Grand Bahama and Abaco Islands is shown in Figure 3. Masonry construction is the predominant type among residential buildings followed by wood frame construction. Approximately 9% of the residential homes are built using reinforced concrete.

Reported Damage Caused by Dorian

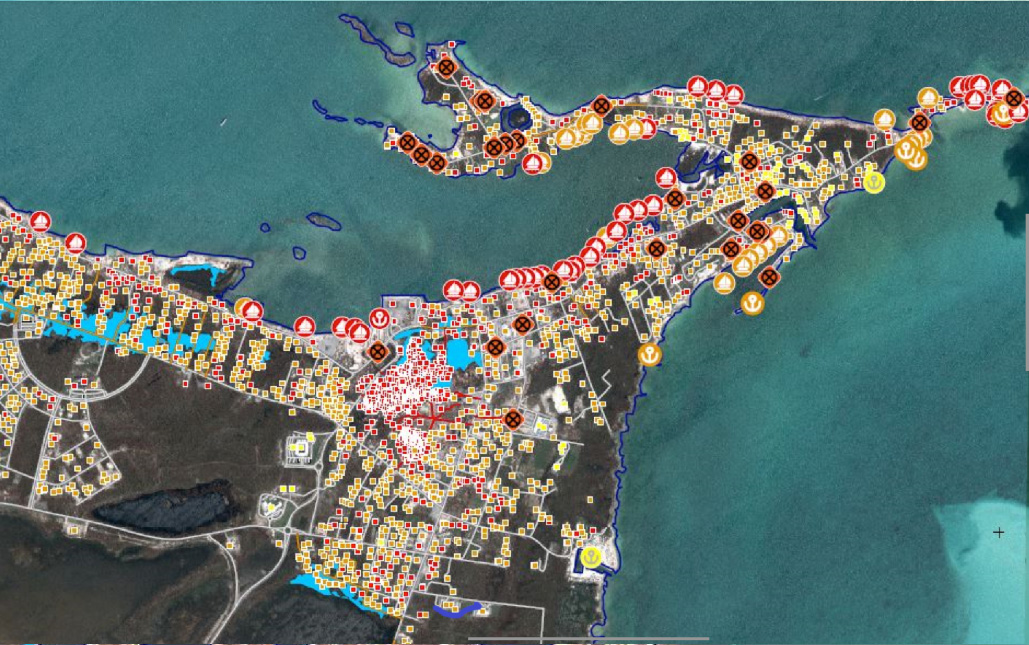

Catastrophic damage was seen in the Abaco Islands, particularly in the city of Marsh Harbour and the district of Hope Town (Figure 4). All structures—irrespective of their construction type—were razed, presenting an almost apocalyptic view. While this destruction has attracted lots of attention, other parts of the Abaco Islands also sustained significant damage.

We noted that the openings in homes seen in photographs of the devastation have protection in the form of shutters that can be mounted before an approaching storm. This is in line with the requirements of the Bahamas Building Code, which we discuss in the next section. The winds experienced by these buildings were so strong and of such long duration, however, that the protection afforded by these shutters was insufficient. Dorian’s Category 5 winds exceeded the design levels of these building systems and led to the collapse of load-carrying components, such as roof ties; the uplift of roofs; and failure of envelope systems, such as walls and roofs. The images in Figure 4 indicate the scale of destruction in the Abaco Islands.

The scale of devastation in parts of Grand Bahama Island, including the city of Freeport, was also unprecedented. Residential and commercial buildings, schools, and airport facilities sustained damage from both wind and surge, and various parts of the island experienced severe flooding.

Although major media outlets have mainly focused on the damage to homes on the Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama, damage to other properties and businesses, including pleasure boats and large industrial facilities, was substantial. For instance, reports indicate significant damage to Burma Oil's storage tanks located in the eastern part of Grand Bahama, resulting in oil leaking to the surrounding areas and posing a serious environmental threat.

The Importance of Building Codes

After conducting damage surveys following Hurricane Michael, which after NHC’s reanalysis was deemed a Category 5 hurricane, one notable lesson learned, among many, was how important building codes were. In a blog post Dr. Tim Johnson, a Senior Engineer at AIR, noted that, “Design wind speeds in the Florida Panhandle are lower than in Southern Florida. Furthermore, much of the exposure in the areas devastated by Michael was constructed before 1995 and was therefore built under codes that predated the lessons learned from Hurricane Andrew.”

The scale of destruction in the Bahamas that has been reported naturally leads us to ask, “What role do building codes play in explaining the damage caused?”

The Bahamas was the first Commonwealth Caribbean country to have a mandatory building code incorporating modern standards. The Bahamas Building Code (BBC) was implemented in the early 1970s and its use is mandatory in building design and construction. When it was updated in 1987 its standards closely followed those of the South Florida Building Code (SFBC); however, it was not updated again and fell out of sync with the major update to the SFBC that followed Hurricane Andrew in 1992. But in 2003, a new edition of the BBC was created based on the ASCE 7 load standards. In addition, design wind speeds increased from 120 to 150 mph and the installation of hurricane shutters was made mandatory for all applicable new buildings.

While the BBC is one the best building codes in the Caribbean, it still lacks thorough specifications and construction detailing requirements for some critical regions and elements of the roof, such as ridges and overhangs, which typically contribute considerably to the vulnerability of not only the roof but also the building as a whole.

In addition to the effectiveness of the standards set out in a building code, their enforcement plays a significant role in vulnerability. In the Bahamas, Ministry of Works’ inspectors visit buildings at various stages of their construction, but because of a lack of resources, training that lacks rigor in some cases, and geography, these inspections are not always very stringent and can result in deficiencies.

Resilience Challenged

It may be extremely hard to pinpoint what led to the destruction of the built environment on this scale—was it, for example, the lack of more stringent building code requirements or the degree of building code enforcement? Either way, the wind speeds in the vicinity of Dorian’s landfall exceeded the design requirements for these buildings—even those built with strict adherence to the BBC. With a changing climate these events may become more frequent and more damaging; it remains to be seen whether the design requirements stipulated in building codes around the world will keep up with this trend. Dorian and events like it remind us that hurricanes can have a devastating impact on people not only while it is ongoing and in the immediate aftermath but also for years afterward.