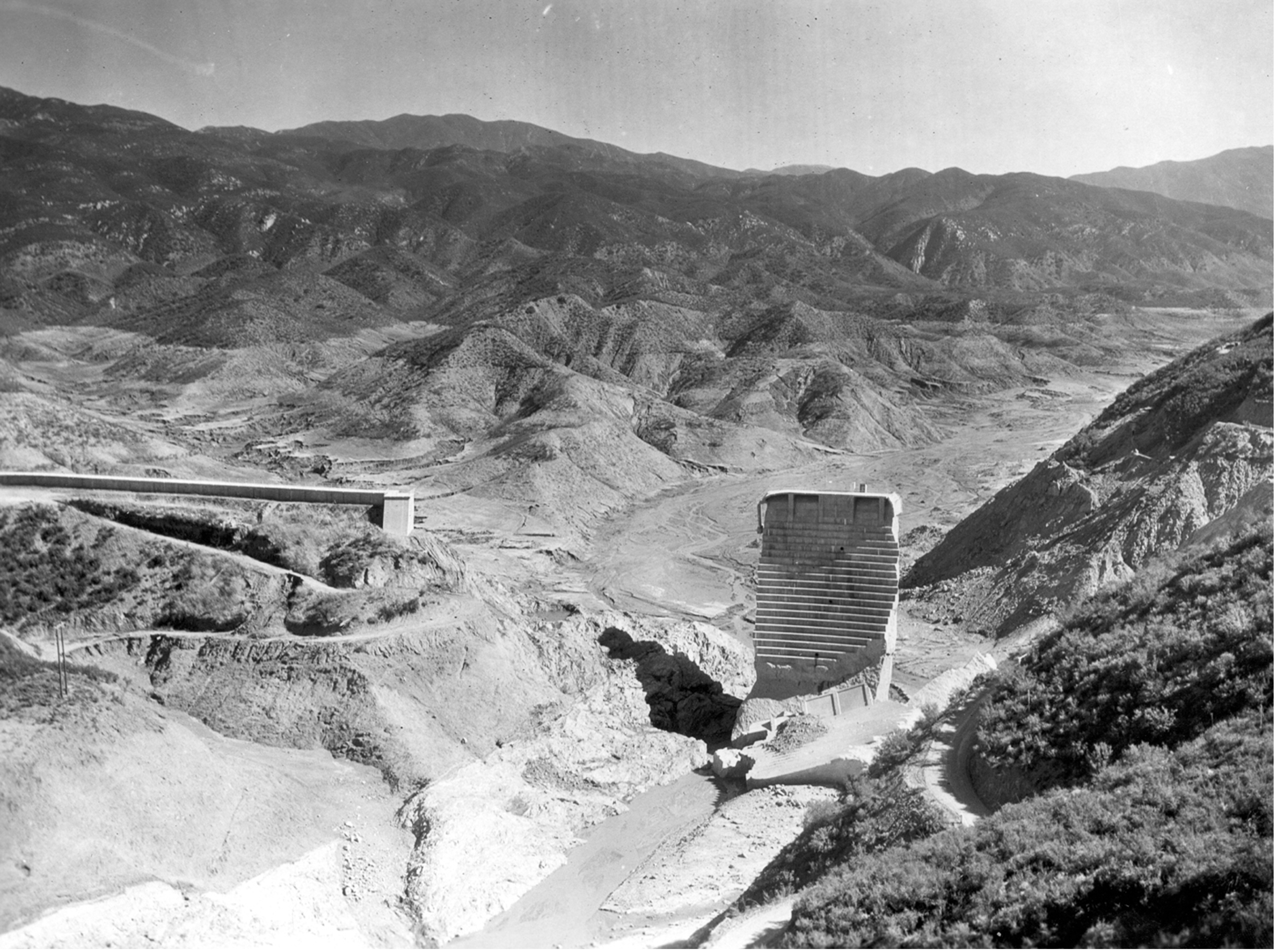

Shortly before midnight on March 12, 1928, one of the dams supplying Los Angeles with water collapsed. The Saint Francis Dam was a concrete gravity dam completed by the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power just two years earlier. It was about 200 feet high and 700 feet wide, and it stored roughly 12.5 billion gallons of drinking water—enough to supply the city for a year.

Unfortunately, dam engineering practice at the time did not require geological research and the dam was unwittingly built over a thrust fault and bedrock subject to disintegration when submerged. Design errors and poor construction followed. Cracks appeared in the concrete as the dam filled, and sloppy operation and maintenance additionally contributed to the tragedy.

The dam’s sudden and unexpected failure released a 120-foot torrent of water to flow 55 miles down the valley of the Santa Clara River to the Pacific Ocean, accumulating debris and washing away roads, bridges, homes, farms, and orchards in the process. In total, more than 450 lives were lost. The largest piece of concrete dislodged from the structure came to rest a quarter of a mile away and measured 115 x 65 x 35 feet. The cities of Santa Paula and Fillmore, about 25 and 40 miles downstream, respectively, suffered severe damage as the torrent flowed through and the wall of water was reportedly still 15 feet high when it reached McGrath State Beach.

Improving Safety

The disaster prompted the State of California to introduce the first dam safety program in the United States; other state programs followed in the wake of subsequent failures. In response to the Buffalo Creek flood disaster, the 1972 National Dam Inspection Act empowered the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to inspect high-hazard non-federal dams nationally to evaluate their safety. The National Dam Safety Program, a partnership of states, territories, federal agencies, and other stakeholders led by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), was authorized by Congress in 1996. And to remind people living and working near dams to have an emergency plan in place, FEMA designates May 31—the anniversary of the catastrophic 1889 failure of the South Fork Dam—National Dam Safety Awareness Day.

According to the 2016 update to the National Inventory of Dams there are more than 90,000 dams in the United States; most are privately owned, and they are on average more than 50 years old. While most of these dams are small in scale and have low hazard potential, more than 11,000 have been categorized with a significant hazard potential that could result in considerable economic loss. Another 15,000 are deemed to have a high hazard potential and to threaten public safety. These at-risk dams are to be found in almost every state.

Growing Risk

The risk is very real. State dam safety programs reported 173 dam failures and 587 "incidents" that, without intervention, would likely have resulted in dam failure between January 2005 and June 2013. The Association of State Dam Safety Officials’ website notes that, “as the nation’s dams age and population increases, the potential for deadly dam failures grows.” A third factor contributing to the growing risk is climate change.

Dam failures are rare events, but when one occurs there is usually some underlying deficiency in the structure that is a causative factor. These can include:

- Inferior construction materials and/or techniques

- Geological instability or earthquake shaking

- Poor maintenance

- Human, computer, or design error

- Internal erosion (earthen dams particularly)

- Seepage causing sinkholes in the dam

Usually, such deficiencies are not individually sufficient to cause a failure but a combination of them can be dangerous. The additional factor that can trigger the failure of compromised dams is often heavy rainfall. Precipitation was a major cause of the Oroville Dam emergency in 2017, for example, and the sequential failures of the Edenville and Sanford Dams in 2020. Climate scientists have confidence that for perils such as extreme heat, inland and coastal flooding, and wildfires, warming temperatures are making some catastrophic events more likely. It seems probable that as the climate warms heavy rainfall will increase and be produced by fewer but more intense events, and that is not good news for high-hazard dams.

Read “Imagining the Worst: What if the Oroville Dam’s Auxiliary Spillway Failed Catastrophically?“