This March it may have felt as though we were well into peak tornado time, but that is yet to come. Tornadoes can occur at any time of year in the U.S. but activity peaks from April through June. In March it generally ramps up significantly, and the month can see twice as many tornadoes as February. May is the top month for tornado touchdowns in the U.S. with an average of 276 for the period 1996–2015. March sees 76 on average, but 192 were reported in the record year of 2017 and only 11 in 2015.

So far in 2021 we have experienced multiple outbreaks of severe weather, particularly in the southern states, and tornadoes keep hitting the headlines. When a burst of severe weather passed through Texas to North Carolina on March 27-28, for example, 15 tornadoes were reported in four states—eight of which occurred in Arkansas and five in eastern Texas.

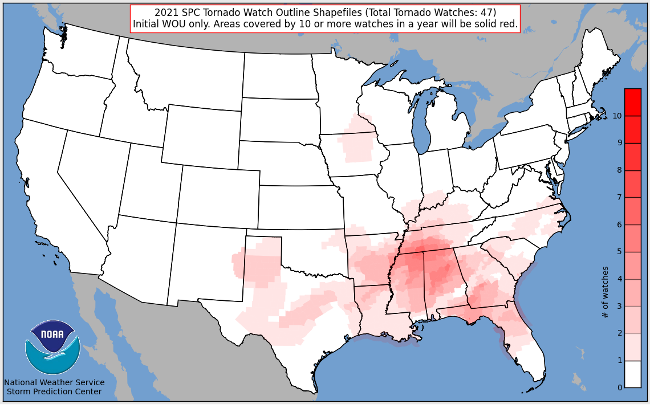

The preliminary data provided in the Annual Severe Weather Report Summary 2021 from the Storm Prediction Center (SPC) notes tornado reports spiking alarmingly in March, with 135 twisters reported after just 11 were noted in February and 16 in January (Figure 2). According to the SPC, so far this year Alabama has experienced 55 of the 162 tornadoes reported, Texas 35, Georgia 15, Florida 13, and Mississippi 12 (Figure 2). From 1 to 5 have been reported in Arkansas, California, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington. The busiest day for tornadic activity so far in 2021 was March 17 (56 reported), and of the top 10 days listed the first four and two others occurred in March.

March 17 saw southern states experiencing severe weather yet again as a winter storm delivered a late season blizzard to the Southern Plains. Unusually for March, the SPC issued a high risk alert. EF-0 to EF-2 tornadoes touched down from March 16 to 18 and homes and businesses experienced severe damage, particularly in Alabama—where 16,000 customers lost power—and in Mississippi. March 18—the fourth most active day of the year to-date—saw nine EF-0 to EF-2 twisters touch down.

March 25 saw the SPC issue a second high risk alert in the month and 23 tornadoes were reported as part of a March 24-28 outbreak consisting of at least 32 twisters. Most of the March 25 tornadoes were estimated to be EF-0 to EF-2, but a 50.36-mile path of destruction resulted from an EF-3 in Alabama and an EF-4 struck Heard, Coweta, and Fayette in Georgia.

The basic ingredients for severe weather are well known: moisture, instability, vertical wind shear, and a mechanism that will cause air near the ground to be lifted. Each must be present in the right amount at the right time for tornadoes, hail, and strong winds to form. Individual tornadoes may be impossible to predict due to the chaotic nature of the atmosphere, but meteorologists can forecast severe thunderstorms that may spawn tornadoes and can spot larger-scale weather patterns likely to influence tornadic activity. Chief among these is La Niña, which is most often associated with its influence upon tropical cyclone formation in the Atlantic basin but has other impacts too.

La Niña can introduce atmospheric instability and affect the jet stream, making it more wavy, increasing wind shear, and generally making powerful thunderstorms more likely. In years when La Niña is experienced—such as 2021, for example—tornadic activity can be enhanced. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration hot and humid air is concentrated over the southern U.S. in La Niña years, setting up a strong north-south temperature gradient, which can favor storm formation.

According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) the 2020-2021 La Niña event has passed its peak, but there is a 65% likelihood that it will persist through April and its impacts on temperatures, precipitation, and storm patterns continue. The WMO notes a 70% chance that the tropical Pacific will return to El Niño-Southern Oscillation-neutral conditions by late spring.

The Madden-Julian Oscillation and other atmospheric factors can also influence the frequency of tornadoes, however, and no one factor is responsible for the likely degree of tornadic activity. If environments could be clearly linked to global-scale climate patterns such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), then seasonal prediction of tornadoes could become more reliable. This is an active area of research in the meteorological community, but we are not there yet.

Severe thunderstorms are no longer viewed as an attritional risk. While the losses from individual thunderstorms in the U.S. are generally lower than those from individual hurricanes or earthquakes, the annual aggregate losses from them have accounted for approximately one half of all U.S. natural catastrophe insured losses since 1990.

Fortunately, a lively start to the year’s tornadic activity does not necessarily mean that the year will be an above average one. The year 2012, for example, began very actively but ended up being one of the least active of recent years. Let’s hope that 2021 follows a similar pattern.

Be proactive and own your risk with AIR severe thunderstorm models.