Tropical cyclones are usually solitary phenomena, but on rare occasions they can get up close and personal. Tropical cyclones all rotate in the same direction—counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. If the centers of two storms come within ~900 miles of one another, the storm systems can start to interact, or as NOAA puts it rather poetically, “they begin an intense dance around their common center.” This is known as the Fujiwhara Effect.

It is rare for tropical cyclones to interact this way, but not unknown. If one of the cyclones is less powerful, it will begin to orbit the stronger storm and will eventually be drawn into it and absorbed. The true Fujiwhara Effect occurs when two storms of similar strength meet and begin orbiting around the central point between them; the vortices will generally be attracted to one another and can merge. In either case the effect is generally detrimental to one or both storms and they don’t merge to create one more powerful cyclone. The effect happens most frequently in the northwest Pacific basin because of the high number of storms that form there.

The effect, which is also noted in whirlpools in water, is named for the Japanese meteorologist Sakuhei Fujiwhara (1884-1950), who first described it in his 1921 paper, “The natural tendency towards symmetry of motion and its application as a principle in meteorology.” Dr. Fujiwhara—who was also a noted seismologist—was director of what is now the Meteorological College of Japan before becoming a professor at Tokyo Imperial University and director of the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA).

Typhoon Noru and Tropical Storm Kulap interacted in this way in the western Pacific in late July 2017. Remarkably, at the same time Hurricane Hilary and Hurricane Irwin were dancing around their common center in the eastern Pacific Ocean as their eyes came within 400 miles of one other. Irwin revolved counterclockwise around a weakening Hilary before the two merged and dissipated. More recently, in August 2020 two tropical cyclones in the Gulf of Mexico at the same time—a rare event in itself—followed close and converging tracks that looked for a while as if they might interact. In the event, however, hurricanes Marco and Laura stayed apart.

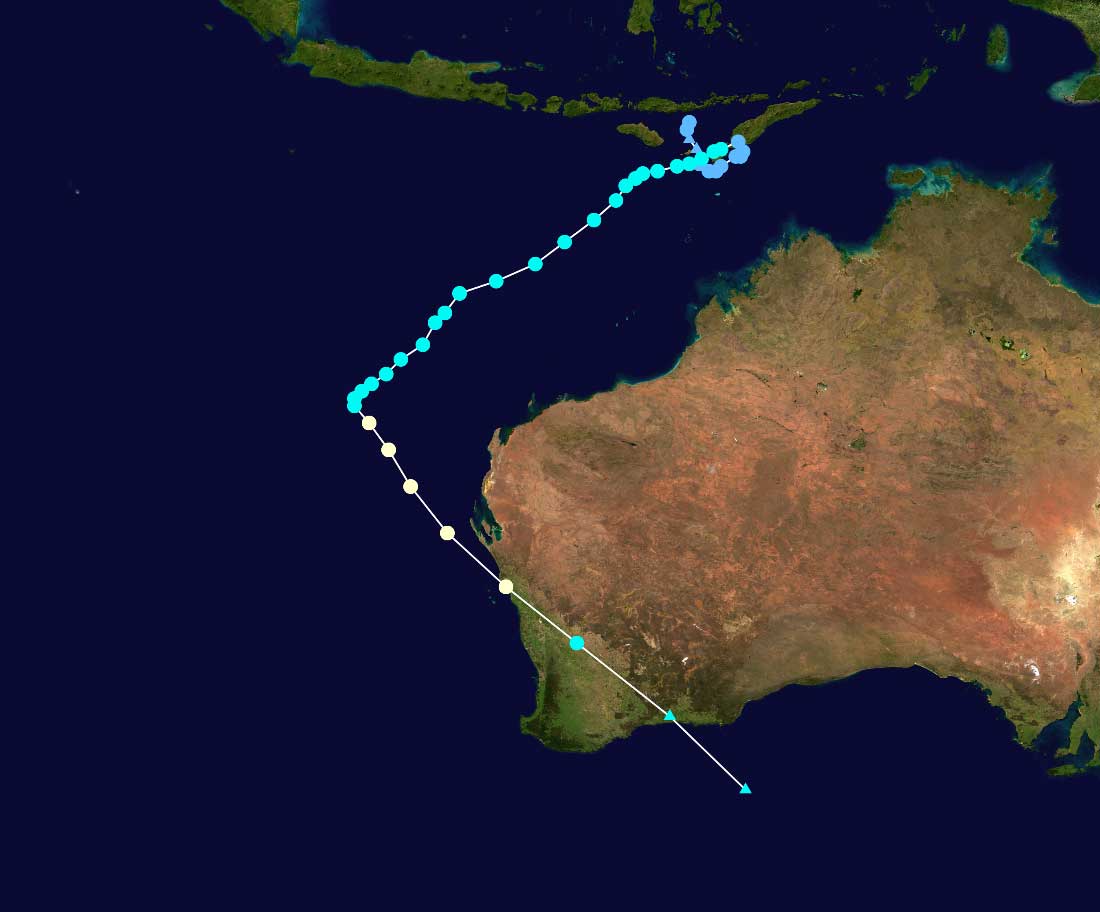

More recently still, Tropical Cyclone Seroja—already responsible for deadly flooding and landslides in Indonesia—and Tropical Cyclone Odette interacted April 7-9, 2021, off the coast of Western Australia (Figure 1). Odette orbited clockwise around Seroja for almost one whole rotation, impacting the coast near Exmouth as it did so, before it was absorbed by the dominant storm. Seroja maintained its intensity and made landfall at about 7 p.m. local time about 300 miles (500 km) north of Perth on April 11. It came ashore between Geraldton and the small resort town of Kalbarri, where it caused widespread damage. About 800 structures in Kalbarri—roughly 70% of the total number—were evidently damaged, some significantly; 32 buildings were reportedly destroyed.

The Bureau of Meteorology in Australia (BoM) uses an intensity scale to categorize tropical cyclones by central pressure or 10-minute maximum sustained wind speeds. This scale places tropical cyclones into five categories of increasing intensity; tropical cyclones at Category 3 or above on the BoM scale are considered Severe Tropical Cyclones. Seroja came ashore rated as a Category 3 storm (10-minute maximum sustained wind speeds between 118 and 159 km/h). It maintained its strength for about 1,000 km (620 miles) as it moved southeastward across the state’s wheat belt but eventually began to weaken. In addition to strong winds, Seroja delivered heavy rainfall to the region; fortunately, its forward speed was fast enough to avoid significant flooding, but localized flooding was experienced thanks to rainfall totals of 3-6 inches. In addition, trees fell and more than 31,000 customers lost power.

Seroja’s brief interaction with Odette is interesting because of the Fujiwhara Effect but noteworthy because of how it impacted the surviving storm’s landfall. Tropical cyclones in Australia tend to occur far more frequently near the northern half of the continent, generally above 30° latitude south as most form off the northwest coast (Figure 2). The most exposed areas are along the vast stretch of northern coastline running from Geraldton to Port Macquarie in New South Wales on the other side of the continent. At one time Seroja had been thought likely to strike the Pilbara Coast in the north of Western Australia—which has the highest exposure in the country to tropical cyclones—but interaction with Odette shifted its track southward to the Central West Coast.

When Seroja made landfall north of Geraldton it was moving steadily southeastward, making its path through the state an unusual one (Figure 3). It is extremely rare for tropical cyclones to travel this far south and Geraldton has not experienced such a storm since 1956. Of the four wind speed zones into which Australia’s building standard divides the country, the Central West Coast is in Wind Region B—considered not prone to these events and with the second lowest wind design speed values. As a result, the damage done by Seroja was severe. Hopefully southerly storm systems like this will remain rare occurrences.

Read “Managing Tropical Cyclone Risk Down Under“