Back in October 1987 the BBC weather forecaster Michael Fish infamously reassured viewers that there was no hurricane heading for the southern UK. Contrary to popular perception, he was talking about a weather system out in the North Atlantic. In the same forecast he correctly warned of strong winds from another storm coming up from the Bay of Biscay, but the unusually powerful winds that storm delivered still came as a major shock to the region.

For several hours southern England was battered by sustained winds of more than 75 mph and in the county of Sussex an anemometer failed after experiencing gusts of more than 120 mph. Damage was widespread and severe. Boats were wrecked, buildings were damaged, and power outages occurred. All over the southeast about 15 million trees were toppled; the town of Sevenoaks in Kent lost six of the ancient trees it is named after.

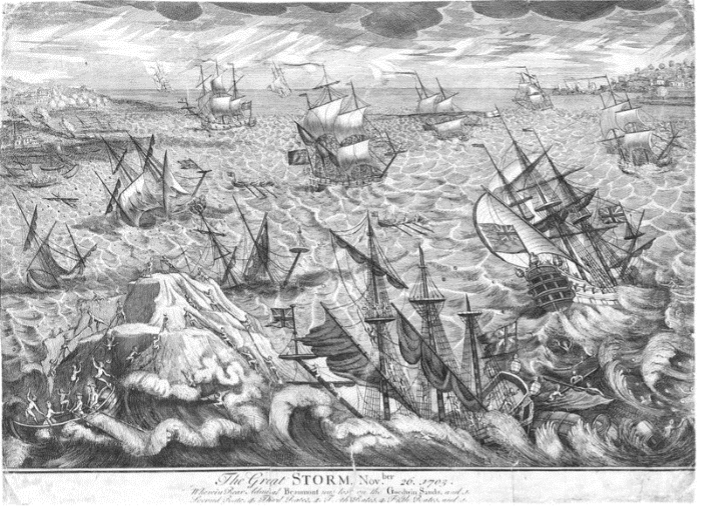

The Great Storm of 1987 was exceptional, but not unique. Another Great Storm of similar strength struck central and southern England on December 7, 1703 (November 26 according to the Julian Calendar used at the time).

Much of the damage from that storm was done to ships at sea. Lucky vessels were blown far off course, others were driven ashore—one was reportedly found 15 miles (24 km) inland—and many sank. Thirty vessels from a convoy of 130 sheltering in Milford Haven were wrecked, and the Royal Navy lost a total of 13 ships, including the entire Channel Squadron together with its rear admiral; at least 1,500 sailors died. On a rock several miles out in the Channel off Devon the wooden Eddystone Lighthouse, completed as recently as 1698 and the first recorded offshore lighthouse, disappeared almost without a trace. With it went its designer, who was there making alterations.

On land the damage was equally catastrophic. Many thousands of trees were toppled and more than 4,000 oaks fell just in the New Forest. At least 400 windmills were destroyed; the wind drove the machinery in some so violently that the friction reportedly caused them to catch fire. Many chimneystacks fell—about 2,000 in London alone—and there was widespread building damage. The west window of Wells Cathedral was blown in, lead roofing was stripped from Westminster Abbey, and stone pinnacles crashed down from the parapet of Kings College Chapel in Cambridge. Church roofs and spires across the region were damaged, many homes—particularly poorly built ones—were damaged, and countless rickety outbuildings collapsed.

At least two tornadoes were seen, one of which lifted a boat onto dry land and a cow into the branches of a tree. Flooding occurred, particularly in the West Country, where the River Severn rose 8 feet above its normal level. Bridges washed away and livestock losses were significant; much prime farmland was contaminated with saltwater, affecting harvests for years to come.

It is extremely difficult at this remove to ascertain the true extent of the damage experienced. Records are few and contemporary estimates were often wildly exaggerated. Presumed shipping losses, for example, proved to have been inflated once scattered ships began returning to port. Nevertheless, this was clearly an extremely damaging and costly storm.

In an early example of demand surge, prices for building materials rose sharply in the wake of the storm. Plain roof tiles, for instance, increased from just over £1 per 1,000 to £6 and fancier pantiles from £2.50 to £10. For many the cost of rebuilding proved prohibitive, and their homes remained roofless through the following winter while others made do with temporary measures.

For most people, without any form of weather forecasting available, the storm came almost without warning. The writer Daniel Defoe saw the mercury in his barometer fall lower than he had ever seen it and accused children of tampering with the instrument. In Essex, William Derham measured the storm’s barometric pressure at 973 millibars, and it is thought that the storm probably deepened to 950 millibars as it passed through the Midlands on its way to the Netherlands and Denmark. It has been estimated that winds were likely the equivalent of a Category 2 hurricane.

Storms of this severity impact northern Scottish islands in the Hebrides, Orkney, and Shetland every 30 to 40 years but while they strike southern England far less often, they should not be unexpected. According to the UK Met Office, “analysis of records of the hourly mean wind speeds and highest gusts indicates that such extreme conditions over land in south and south-east England were likely to occur, on average, only once in 200 years.” Southern England, however, experienced storms almost as notable in 1792, 1825, and 1839.

Countries across Europe are susceptible to extratropical cyclones. Fortunately, the AIR Extratropical Cyclone Model for Europe helps you assess the risk from wind for single storms as well as storms clustered in space and time, including the most extreme events.

Advance your risk management capabilities with AIR extratropical cyclone models.