The year 1356 may seem a long time ago, but in terms of the geologic time scale, it is very recent. Historically, most destructive European earthquakes have occurred in the Mediterranean countries, particularly Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Turkey, but earthquakes are widespread throughout Europe. Switzerland, for example, experiences low levels of background seismicity and large, infrequent intraplate events. A magnitude 6.4 event occurred near the Swiss town of Visp in 1855, for example, and the strongest earthquake known north of the Alps devastated the city of Basel on October 18, 1356.

Seismic activity in Switzerland and surrounding countries tends to be concentrated along the Alps, the Jura Mountains, and the Rhine Graben—a rift system extending into northern Switzerland. Basel, on the River Rhine in northwestern Switzerland close to where the Swiss, French, and German borders meet, lies in one of the most earthquake-prone regions of the country.

From about 6 p.m. on the feast day of Saint Luke the Evangelist (October 18 in 1356) a series of strong foreshocks began to rock the city, which was then the seat of a Prince-Bishopric with a population of about 7,000. The initial quakes caused minor damage such as toppled chimneys and prompted many inhabitants to flee into the surrounding fields. Then, at about 10 p.m., the mainshock struck with a magnitude estimated to have been about 6.5; the epicenter may have been immediately to the south of the city.

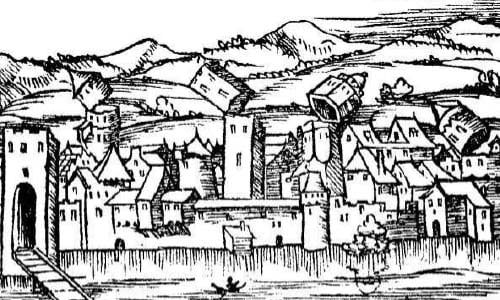

Unreinforced masonry structures—brick and stone houses, fortifications, and churches—suffered severe damage; those that did not collapse developed major cracks. Timber framed homes fared better, however, with their first floors often surviving while upper stories fell. The city walls toppled in many places and one Medieval account claims that barely 100 houses remained standing. There are no reliable records of casualties and estimates range wildly from 100 to 1,000 killed; clearly more would have died had so many people not evacuated themselves from the city after the first shocks.

Fires began to break out soon after the initial earthquakes and, fueled by the many timber structures and shingle roofs, reportedly could not be extinguished for eight days. The central portion of the city and the suburb surrounding the St. Alban monastery were gutted. Furthermore, homes lining the Birs, a tributary of the Rhine, fell into the river and blocked its flow. The ensuing flood severely damaged the stonework of the monastery of Mary Magdalene.

Damaging shaking was experienced across an area of about 500,000 km2; the quake was felt as far afield as Zürich, Konstanz, and the Île-de-France. Basel, Lörrach, and Liestal were badly damaged and churches, castles, and fortifications within a radius of about 30-km from the epicenter were largely destroyed. A total of at least 63 castles in the wider area were badly damaged. Aftershocks continued to occur in the region for the remainder of the year, some of which caused additional damage.

With generous assistance from communities in the wider region, Basel was able to rebuild and recover comparatively quickly. Aid came in the form of workers, carts, horses, equipment, materials, and money. The cathedral, for example, was rebuilt and reconsecrated within six years. The cause of the disaster was not at all understood, and many blamed it upon divine displeasure.

Today, Basel is Switzerland's second largest urban area and its third most populous city, with a population of 564,203 in the urban area and 164,488 within the city itself. Basel is among the most important cultural centers in the country and is a railway hub with an extensive transportation network. Churches, archaeological sites, and numerous museums are located there, as well as several high-rise commercial and apartment buildings.

Underlying the Pan-European region is a vast and complex pattern of plate boundaries and crustal faults that have produced some of history’s most devastating earthquakes. While the hazard is highest at the plate boundaries impacting Turkey, Italy, Greece, and Portugal, the rest of Europe is also subject to varying levels of earthquake risk. In some cases, such as Switzerland, it is precisely the relative infrequency of seismic activity that makes the exposed population and properties especially vulnerable. In a region with high-value exposure, companies need sophisticated tools to help them prepare for the next high impact event.

Learn about AIR’s Earthquake Model for the Pan-European Region