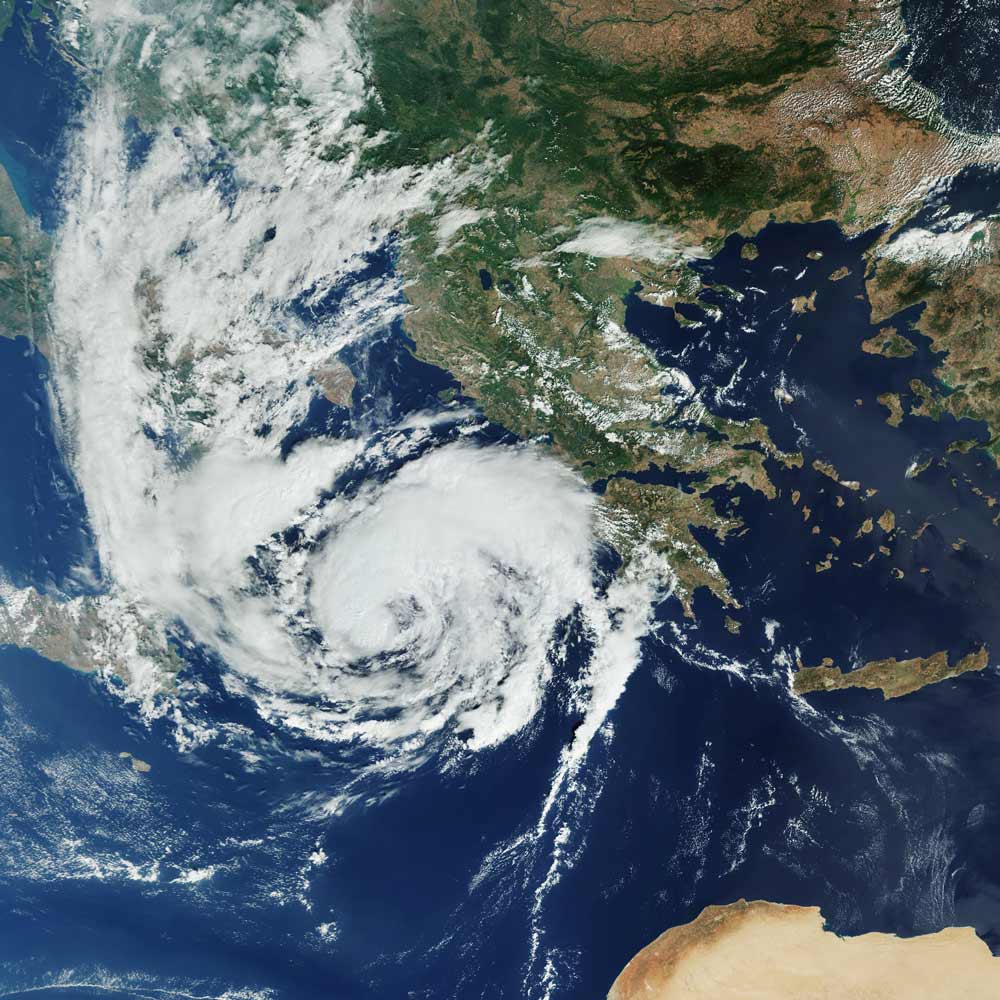

Think of Greece and you’ll likely picture white-washed villages atop rocky islands, stunning beaches, and ancient ruins. But even a picturesque idyll such as this can experience natural catastrophes. Of late, the country has been ravaged by flash flooding, wildfires, and droughts plaguing the mainland and islands alike. One such natural catastrophe that recently affected the region is a cyclonic storm referred to colloquially as a “medicane” (i.e., Mediterranean hurricane) for its resemblance to the tropical cyclones found in the North Atlantic or Pacific basins. I learned about this type of storm the hard way—on a vacation last month when a storm named Ianos made a visit.

This natural phenomenon is nothing new—Greek manuscripts centuries old record the rising tides, winds swirling around a center point, and flooding rains from such cyclonic storms—but only since the late 1940s has there been research into their development and impacts.

Most medicanes form either in the western Mediterranean Sea between the Balearic Islands, France, and Sardinia, or in the Ionian Sea between Greece, Italy, and northern Africa. Their occurrence is rare, with fewer than 100 recorded in the past 70 years. Unlike in the tropical basins of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans, in the Mediterranean the Sahara Desert elevates temperatures and suppresses humidity; however, the mountainous terrain surrounding the sea and islands is conducive to localized convective activity. When key ingredients such as surface moisture, warm sea temperatures, and minimal wind shear are present, any existing convection in the basin may develop cyclonic characteristics.

Most medicanes tend to occur during the transitional periods of weather between summer and winter when sea surface temperatures are high and moisture infiltrates the basin from the Atlantic as the jet stream starts to dip farther south. Medicane activity tends to peak in January but can occur as early as September.

Ianos

In mid-September 2020 meteorologists began monitoring an area of low pressure in the Gulf of Sidra that quickly developed into a cyclone, forming a warm core near the surface. Aided by above-average sea surface temperatures of 27-28°C, the storm rapidly intensified on its journey north and east to the Ionian Sea and was named Ianos by the Hellenic National Meteorological Service. The storm wreaked havoc on the Ionian Islands and some inland areas of Greece, cutting power, toppling trees, and dropping over a foot of rain amid sustained winds nearing 70 mph (hurricane-force winds start at 74 mph).

My partner and I happened to be staying on the island of Kefalonia when Ianos struck, having planned a two-week holiday for some sun before the onset of winter in the UK. Keeping an eye on the weather is second nature to someone in the cat modeling industry, and, while our sun-soaked holiday plans were upended, riding out this storm quickly turned into a riveting opportunity to experience a rare natural catastrophe (safely, of course!).

We arrived Saturday, September 12, under blue skies and light breezes but as the storm gathered strength and headed toward us the weather changed. On September 17 a brisk southerly wind picked up and a warm rain began to fall. We could see the waves pounding on the shore and the cerulean blue water churned into a muddy brown dotted with whitecaps; the power was cut mid-morning.

As the afternoon wore on, the rain continued falling and the winds picked up. Giant eucalyptus trees, groves of ancient olive trees, and old Mediterranean oaks swayed in the wind, but it wasn’t strong enough yet to topple trees or rip off any branches. Trees here are used to strong winds. As we headed into the evening, the radar indicated an area of dry air which meant a break in the rain but an increase in wind speed. We were awoken at 3 a.m. to all the windows rattling with each gust and the wind whipping through and tearing about the vegetation.

After a wet and windy night during which we managed to get a couple of hours of rest, dawn on September 18 brought the calm of the eye; the skies had cleared and there was no wind. Hundreds of disoriented birds caught in the eye flapped about, crashing into windows and swooping into the ground. Several trees had lost branches or had limbs dangling precariously. The surrounding fields were wet and the pool was near to overflowing thanks to at least four inches of rain falling within a few hours. The wind became northerly and much stronger, but the wind and rain subsided into the evening and we woke up the next day to review the damage.

The natural harbor at Argostoli, which normally protects the largest town on the island from westerly winds, experienced storm surge that damaged north-facing businesses, homes, and power stations exposed to the strongest winds. Around 10 to 12 inches of rain fell on an island that normally sees half that amount in any given year. The wet soil and strong winds toppled a significant number of trees, with many falling onto homes, power lines, and roads. Kefalonia is a mountainous island, so there were many roads breached by the sudden rush of water; infrastructure and services on the island were not built to withstand sustained winds of 65 mph. Fortunately, most homes are built of masonry with either slate or tile roofs and fared well, and as the island is primarily porous rock most of the rainfall percolated quickly into the groundwater or flowed to the sea, minimizing inland flooding.

Sea surface temperatures in the Mediterranean have been trending warm for several years now, a factor we know is critical to the development of storms with cyclonic characteristics. In the past several years, explosive thunderstorms and storms with cyclonic elements, like Storm Ianos, have been increasing in frequency and severity. The Hellenic National Meteorological Service reported that Ianos produced the strongest observed winds on record. While damage to property was minimal, the impacts to businesses, trade, and infrastructure will likely take weeks to remediate and in many cases, with the downturn from COVID-19, will further strain already stressed businesses and public resources.

Read the blog “Yes, Tsunamis Really Do Happen in the Mediterranean”