Editor’s note: A version of this article was originally published by Insurance Day on July 13, 2020 as “Why Lloyd’s underwriters need to check their catastrophe rates due to climate change“

Cuthbert Heath was an innovative underwriter working in the two decades before the 20th century and his name is well known to the Lloyd’s market. Among his many achievements, he was the first Lloyd’s underwriter to accumulate detailed probability of loss statistics on earthquakes and windstorms. He estimated the level of hurricane risk in the Gulf of Mexico by collecting comprehensive data from the early 1890s. Heath estimated future losses by calculating the average rate of loss observed in historical records. This historical rating approach was innovative for its time and set Heath above his peers.

Two decades into the 21st century, we see significant weather disasters that raise concerns about the risk climate change poses to the insurance industry. A higher global temperature is causing extreme weather events, such as droughts, wildfires, floods, and hurricanes to occur more frequently and with higher intensity, placing the re/insurance industry uniquely at risk. With insurance claims potentially increasing, so too must the price of insurance.

How would Heath, the “father of modern insurance,” tackle the climate change challenge if he were alive today? Knowing how underwriting rates are calculated is essential to understanding how well they reflect the actual risk.

According to a report from Aon, underwriting a profitable property book in the Lloyd’s market is challenging at present—as shown by recent results, with the combined ratio for the property class of business at Lloyd’s running at 128% in 2018. Lloyd’s has begun to address these challenges with its Decile 10 review, although this is focused on addressing the short-term profitability of the property class at Lloyd’s.

It is of paramount importance underwriters use high-quality data and are comfortable with their underwriting rates. Although catastrophe models are, for the most part, widely used in the insurance market, many underwriters still price policies using internally developed tools and rates. Some market practitioners believe underwriting is an art, not a science, and there are many methods underwriters can deploy to underwrite a property policy, which have their own pitfalls and advantages:

Historical (“burn”) rating, where underwriters take actual loss histories and use this as a basis for future losses, loading for expenses, and profit as appropriate.

Catastrophe modeling metrics, such as an average annual loss (AAL), a loaded AAL or tail value at risk (TVaR) and return period loss (for example, one-in-100-year or one-in-250-year return periods).

Pure rating, which is explained in further detail next.

Pure Rating

Most insurance policies are priced by applying a derived rate against the insured value or limit exposed. In the property market, sometimes scales such as a first-loss scale are also used as part of the process. For a typical property policy, an underwriter may use some form of this equation:

Premium = rate × insured value

where the rate is expressed numerically per USD 100 of insured value (for example, a rate of 75¢ per USD 100 means the cost to the insured is USD 0.0075 per USD 1 of insurance coverage).

Throughout the marketplace, there are many variations of this concept. For example, an underwriter could choose to rate against a probable maximum loss (PML) instead of the insured value, assuming there is comfort in using the PML. The key takeaway is the rate reflects the risk. For example, a “risky” rework factory may have a rate of as much as USD 4 per USD 100, while a “vanilla” office block could have a rate of just 15¢ per USD 100.

This concept is used for both non-catastrophe rating (for example, re) and catastrophe rating (for example, U.S. hurricane), although, of course, different scales and rates will be required depending on the underlying risk being rated. The only difference for catastrophe rating is aggregations of catastrophe risk must be combined to create “pots” of aggregate. An easy method is to use Cresta zones (for example, California A1), groups of counties (for example, Florida Tri-County) or even custom zones defined by underwriters (for example, wind gates). Rates are applied to these “pots,” again reflecting the risk.

Many of the rates used by underwriters in the market are “legacy rates” passed down from one generation of underwriters to another. They are notoriously difficult to update as they are used in various parts of the business, such as year-on-year rate change metrics, business planning, and reserving. Often, a potential change to these rates is met with fear, uncertainty and doubt.

Heath certainly knew where his rates came from. The question to pose to modern-day underwriters is: “Do you know where your rates come from?” Of course, pricing consistency is vital for clients, but in a changing climate, it is imperative to use catastrophe rates that reflect both the present and future climate to ensure technical adequacy.

The ultimate role of any insurance company is to ensure the premiums collected are appropriately priced to cover the insurance claims in the future. As highlighted by Convex founder Stephen Catlin, if companies are not able to do this, they may face the challenge of under-reserving due to inadequate pricing as seen in recent months with casualty classes of business.

Catastrophe Models

The catastrophe models’ output is insured property loss metrics, which includes policy and exposure information. Using catastrophe models’ metrics such as AAL, underwriters can calculate an appropriate rate and charge premiums accordingly.

Underwriters traditionally use the best available historical data to simulate potential risk. With climate change, however, historical data may be associated with significantly different climate conditions, which no longer reflect the risk today. A year-to-year view of risk fails to recognize an individual class of business cannot be re-underwritten in one year. Assuming the retention rate of 90% for an insurer, it may take up to 10 years to adjust an individual class of business.

Therefore, incorporating a new catalog of events that represent the present and future view of the climate when generating catastrophe modeling parameters (for example, AAL) is essential for underwriting the risk of climate change. This new catalog could also be used to inform the technical pricing rates used by underwriters.

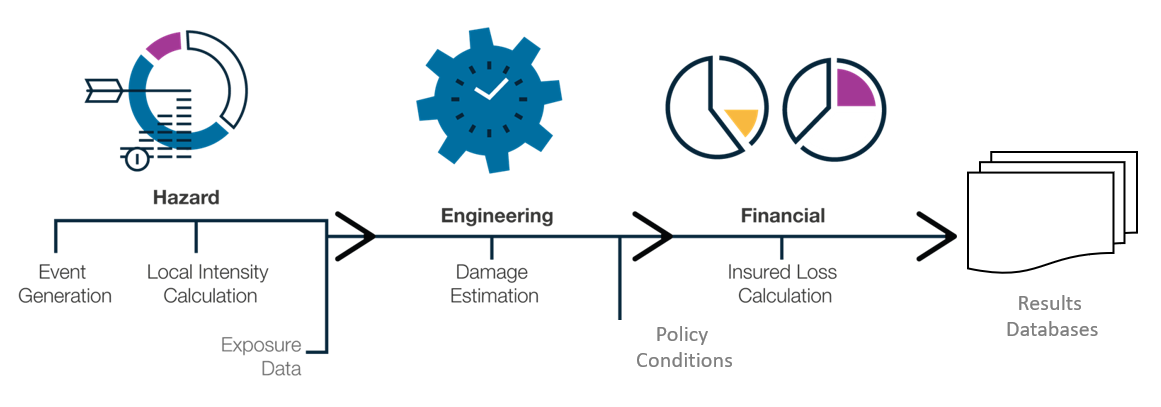

Catastrophe models consist of three modules: hazard, engineering, and financial modules as shown in Figure 1.

Estimating the Present and Future Risk of Climate Change

Atmospheric peril models use catalogs of stochastic events simulated from models trained on the recent historical record that not only reflect the future climate but also give a statistically robust view of the risk posed by it at present. Catastrophe models can be leveraged to help re/insurers update their pure legacy catastrophe (that is, without loadings) rates obtained from our models in different ways:

Custom weather-related climate change catalogs: climate change-conditioned catalogs can be used in the hazard module to calculate the losses and probability of the risk for a future climate scenario. Insurers can then run these catalogs against a given property exposure to determine the climate-conditioned catastrophe rates that reflect a changing climate and provide an accurate representation of the risk, which historical rates do not provide. This conditioned rate could be used for accurately pricing premiums. AIR has worked with the Association of British Insurers to create climate-conditioned catalogs that enable stress-testing of losses under future climate conditions.

Climate change scenarios: underwriters need to consider how significant historical events, such as Hurricane Andrew, may manifest in the future because of climate change. These rare events are complex and different sub-perils may contribute differently to the losses. Climate change scenarios can help underwriters simulate an actual historical event in today’s climate and understand what scenarios will yield the most significant changes in loss, as well as what the probability of such an event occurring in a future climate is.

Custom modifications to model parameters: innovative algorithms can be developed to account for the impacts of climate change, such as sea level rise in coastal regions. For example, AIR assisted the City of Miami Beach with its stormwater management and estimated the average annual loss by 2050 due to the sea level rise of 1 foot.

Exposure accumulation in climate-conditioned hazard maps: customized climate change-conditioned hazard maps can be developed to account for the future risk from climate change impacts to different perils that can be run in catastrophe models to calculate the accumulated exposure in any region (for example, moving the coastline by X feet to account for sea level rise). Financial terms can be applied, and damage ratios can be assigned.

Stress testing existing rates: to underwrite a sustainable and profitable business, re/insurers need to stress test their existing rates to ensure adequacy for future risk. Catastrophe risk models can help formulate and interpret climate-related and other general insurance stress tests. AIR has collaborated with the Prudential Regulation Authority to formulate the core General Insurance Stress Tests 2019 for natural catastrophes and co-authored the Practitioner’s Aide for a Framework for Assessing Financial Impacts of Physical Climate Change.

Building Climate-Resilient Portfolios

Hurricane Andrew inflicted unprecedented losses in 1992 when it slammed into Florida—before catastrophe models had been accepted by the industry—causing several insurance companies to become insolvent and requiring others to be bailed out by their parent companies. Today, relying solely on historical data to estimate the current and future risk from a changing climate could, again, put insurance firms out of business. What would Heath do if faced with the current challenge posed by climate change? His innovative approach suggests he would make the most of cutting-edge technology to find ways to ensure that underwriting rates appropriately reflect the likely risk.

Learn about AIR’s Climate Change Risk Management Solutions