Flood defenses come in many forms and do a great job of protecting lives and property, but they are expensive to build, require maintenance, and can fail. Their Achilles’ heel, as I discussed in an earlier blog, is that they are designed to offer a particular standard of protection—and no more. If a flood is greater than any they were designed to protect against, they can fail or—more likely—simply be overtopped. And as sea levels rise, and if storms become more intense, the protection afforded by defenses will diminish.

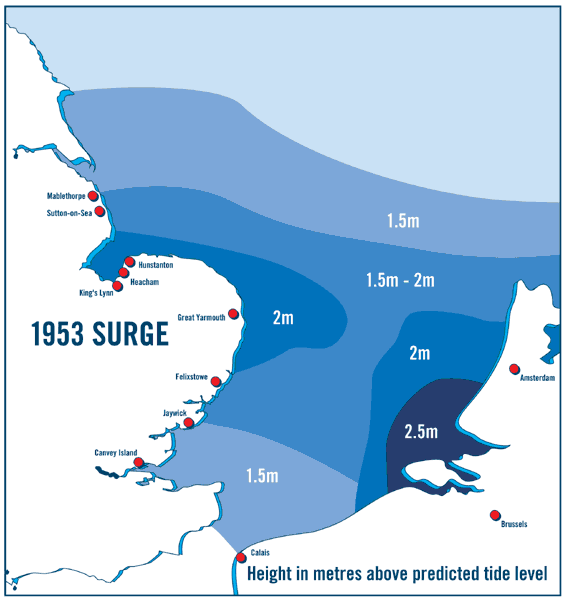

One of the most devastating natural disasters to strike Northern Europe in modern times began when storm surge started impacting the coast of Lincolnshire on the evening of January 31, 1953. A North Sea spring tide interacted with a violent extratropical cyclone and raised sea levels to more than 2.5 meters above normal high tide levels in some places. As it transitions from the North Atlantic to the English Channel, the North Sea gets shallower, and between the coasts of East Anglia and the Netherlands, it becomes progressively narrower still. Southward-traveling extratropical cyclones, the region’s complex tides, and this bathymetry can conspire to generate dangerous storm surges along the eastern and southern coasts of Great Britain and the Dutch coast.

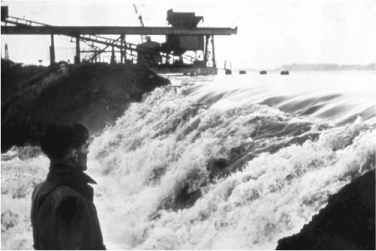

In 1953, many coastal defenses were overwhelmed, with hundreds of breaches reported. Across southeastern England, more than 100,000 hectares were flooded, and about 24,000 homes were damaged. In the Netherlands—where only about 50% of the land is more than 1 meter above sea level and much is below it—1,800 people were killed and 200,000 hectares submerged. In total, more than 2,500 people lost their lives across the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands, and at sea, and about 70,000 properties were inundated.

As a direct result of this devastating storm, comprehensive flood warning systems were established on both sides of the North Sea. Existing flood defenses were strengthened and improved, and huge long-term engineering projects were initiated.

A flood barrier across the River Thames in the UK was proposed soon after the floods of 1953, but construction didn’t start until 20 years later. As well as the famous barrier itself, the project included raising and strengthening flood defenses for 11 miles downriver to protect the capital from surges with a return period of up to 1 in 1,000 years.

The Thames Barrier was built with rising sea levels in mind, but it cannot protect London indefinitely. When it first became operational in 1982, it was expected to be raised two or three times a year, but it is now being raised six or seven times annually. To date, it has been raised on 94 occasions to protect against tidal flooding and 87 times to protect against combined tidal/fluvial flooding. It is already halfway through its designed lifespan, and in a decade or so, the standard of protection it can provide will start to decline gradually; possible replacements are already being discussed.

Another direct response to the 1953 floods was a series of massive construction projects in the Netherlands known as Deltawerken (Delta Works), launched to protect the southwestern part of the country from surges with return periods of up to 1 in 10,000 years. Three river estuaries were blocked to reduce the length of coastline that needed protecting by 700 km (430 miles), and an extensive series of dams, sluices, locks, dykes, and levees was built. Unlike earlier Dutch projects, this engineering work was for protection, not land reclamation.

To keep costs manageable, the levels of protection provided are carefully tailored to the risks perceived. Levels of “acceptable risk” have been established for several zones and enshrined in legislation that requires the government to maintain protection for the levels set and to improve defenses if new insights alter the view of risk. Dutch engineers have been combatting the sea for centuries, and flood protection is a continual focus of debate. Even as they were being completed, plans for enhancing the original Delta Works projects were under way.

Flood defenses can make an enormous difference. In a 2009 study, for example, AIR estimated that had there been no inland flood defenses in place during the devastating UK floods of June and July 2007, insured losses would have been in excess of GBP 6.5 billion—more than double the actual reported loss of GBP 3 billion. Defenses need to be reviewed and enhanced from time to time, however, to ensure that they continue to offer protection against an appropriate level of risk.

To learn more, read “Coastal Flooding in the United Kingdom, 1953 and Now“