There’s been a lot of media attention and even a blockbuster movie hyping the “Big One”—the catastrophic earthquake expected to strike the San Andreas Fault—but it’s not the only major earthquake California needs to prepare for. With dramatic flair uncharacteristic of the profession, scientists have labeled the nearby Hayward Fault a tectonic time bomb, due at any time to produce the next big seismic event in the Bay Area. Like its better-known neighbor, it has a track record of producing large magnitude quakes.

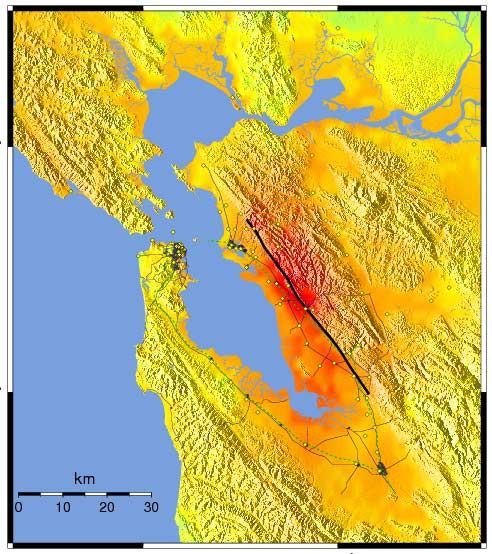

Before the city was devastated by shaking and fire in 1906, the moniker “Great San Francisco Earthquake” belonged to an earlier event. An M6.8 temblor—the strongest in the region since written record-keeping began in 1776—shook the area exactly 150 years ago on October 21, 1868. It ruptured a 20-mile segment on the southern end of the Hayward Fault roughly from Fremont to San Leandro. The average horizontal strike-slip displacement of the fault was around 6 feet and the crack that opened at the surface averaged 6 inches wide. There were 26 aftershocks noted.

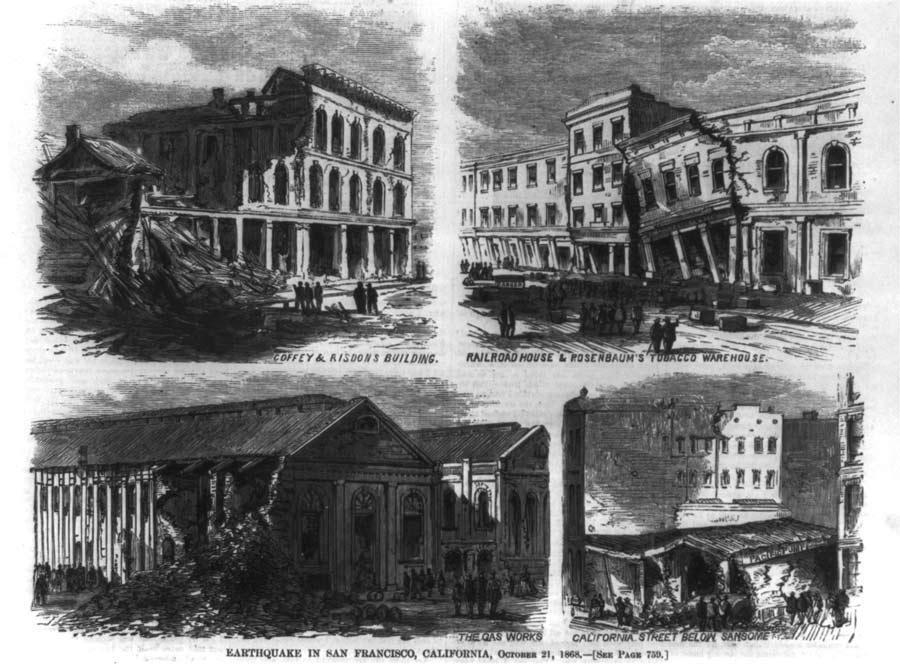

Although the area was sparsely populated at the time, five people were killed and 30 injured. In Hayward, a town of about 500 residents back then, almost every building was knocked off its foundation and rendered uninhabitable. Damage was caused as far away as Napa to the north and Hollister to the south (some 130 miles apart). Notably, shaking was intense across the Bay in parts of San Francisco, which suffered an estimated USD 350,000 in property damage (in 1868 dollars); buildings constructed on reclaimed landfill fared especially poorly.

The Hayward Fault is part of the San Andreas Fault system. It extends approximately 50 miles along the foot of the East Bay hills, from south Fremont into the San Pablo Bay. Like most earthquake faults in the region, it is a right-lateral strike-slip fault; that is, facing the fault from either side, the opposite side moves to the right. Geological monitoring and satellite data reveal that the two sides of the fault are aseismically "creeping" past each other at the surface at a rate of about 1/5 inch per year. This movement, however, does not extend the entire depth of the fault plane and is thus insufficient to relieve the accumulating strain. The long-term movement of the fault is far greater than the average surface creep, meaning there is a potential for major earthquakes to account for the rest of the movement.

Notably, the Hayward Fault runs directly beneath UC Berkeley’s California Memorial Stadium. Because the presence of the fault was well-known when construction started in 1922 it was built with expansion joints where the exterior wall meets the fault. Thanks to the inexorable creeping, however, the structure deformed continually and eventually it became unsafe. It was completely rebuilt within its landmark exterior wall recently, but new cracks have already developed since it reopened in 2012. Last year, the line of the fault was marked for all to see just outside the playing area on the newly installed FieldTurf.

Excavations along the Hayward Fault have revealed evidence of 12 major earthquakes. The last five, which occurred during the period 1315 to 1868, struck at intervals ranging from 95 to 160 years, with an average interval of 138 years. Because it has been 150 years since the 1868 quake, scientists believe that the next one may be due. The USGS estimates that there is about a 30% probability of a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake occurring on the fault in the next 30 years, the highest for any single fault in the Bay Area. This is something the 7 million people who live in the region today need to be aware of.

Because of the hazard and risk, the USGS has been collaborating with key academic, state, local, and industry partners to examine what could happen during a major earthquake in the Bay Area to guide residents and policymakers in earthquake-risk reduction and resilience-building actions. The Haywired Earthquake Scenario study anticipates the impacts of a hypothetical—but entirely plausible—magnitude-7.0 earthquake on the Hayward Fault, and is getting a lot of attention because of the potential damage envisioned.

The study looks at far more than damage to buildings caused by shaking and fires following to indicate likely casualties; it is also evaluating the threat to water supplies and risks to both infrastructure and communications technology. Beyond the immediate physical damage the study is concerned with societal consequences, such as issues for community recovery and effects on jobs and the regional economy.

The HayWired scenario reminds us that we need to learn real world lessons from real world events. Do we really understand the implications of a quake impacting Silicon Valley? What are the likely business interruption issues? Are supply chains sufficiently resilient? What if the water supply goes down?

How well do you really understand your risk?