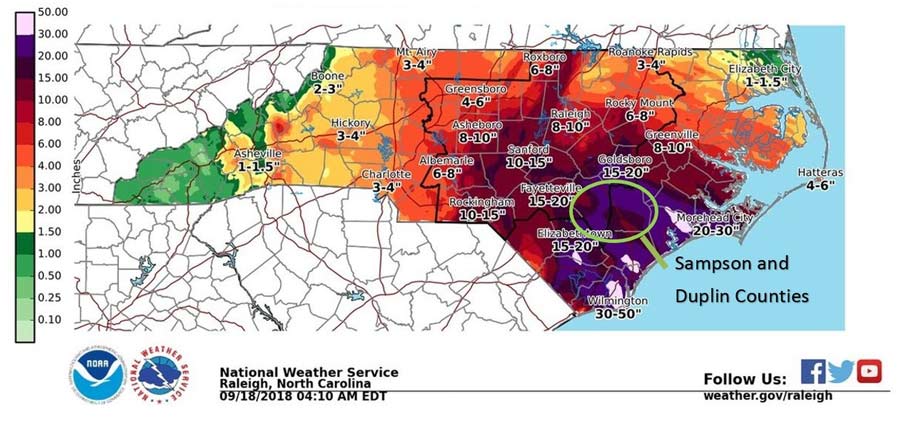

As Hurricane Florence dumped between 15 and 30 inches of rain on southeastern North Carolina, the threat to residents extended beyond the damage wreaked by the rushing floodwaters and the inundated areas. This region is also home to two major sources of pollution—hog waste lagoons and coal ash pits—that contaminated the floodwaters and threaten to turn Florence into a large-scale environmental disaster.

Hog Waste Lagoons

North Carolina is home to some 9.7 million pigs that among them produce 10 billion gallons of manure every year, mostly on industrial hog farms. The majority of these farms are in low-lying Duplin and Sampson counties. Both of these southeastern counties were severely affected by Florence, receiving more than 20 inches of rain.

In these large industrial farms, known as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), thousands of pigs are kept in enormous holding pens. Inside these facilities the 10 billion gallons of manure these animals produce annually falls through slats in the floor to be liquefied and stored in giant open-air lagoons nearby. The contents of these lagoons are used as fertilizer and sprayed onto fields.

On September 16, 1999, Hurricane Floyd made landfall near Cape Fear, North Carolina, as a Category 2 hurricane bringing with it nearly 20 inches of rain, soaking an area that had already received up to 15 inches during the preceding two weeks from Hurricane Dennis. Floyd was responsible for the deaths of 21,000 hogs and resulted in massive environmental contamination of the water supply in the southeastern part of the state. As a result of the investigations into the waste management practices of hog farms that followed, the state bought and relocated many of the most flood-prone farms. Following this voluntary buyout, more than 60 flood-prone farms with 160+ lagoons remained in low-lying areas where they continued to pose a theat.

After Florence, more than 130 of these lagoons either “released hog waste into the environment or are at imminent risk of doing so,” according to data issued on September 26 by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality. Water thus polluted contaminates the surrounding rivers, and coastal waterways that support both fishing and shoreline tourism. It may also impact the drinking water supply. A water supply contaminated with hog waste can lead to a wide array of negative effects for humans, including numerous health problems from gastrointestinal distress to blue baby syndrome, which occurs when excess nitrogen from the hog waste binds to the hemoglobin in a baby’s blood and makes red blood cells unable to carry oxygen.

Smithfield Farms own most hog farms in this region. While studies have identified safer technologies for storing this waste, which could protect local waterways from contamination, the company has not to date taken action, giving as the reason that these solutions are not cost effective. The cost of making any improvements to the waste treatment facilities would fall entirely on Smithfield Farms, while the cost of cleanup efforts is borne by the public—including federal agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), taxpayer-backed state groups like the Division of Soil and Water Conservation and Department of Environmental Quality, as well as local churches and schools. Smithfield Farms has explored ways to prevent these types of disasters but has not yet taken any action. If impacted residents pursue litigation their case should be bolstered by the recent ruling in favor of people affected by the stench from these farms stating that the stench constitutes a nuisance; they were awarded USD 25 million in damages earlier this summer, before any lagoons were breached by Florence.

Coal Ash Pits

In addition to the contamination from the hog waste lagoons, southeastern North Carolina faces another, potentially even more toxic, peril: coal ash pits. Coal ash is the waste material produced when coal is burned to produce energy. It is stored in open air (often unlined) pits (or dumps) that can overflow when inundated with rain. This toxic waste contains carcinogens and neurotoxins, including arsenic, boron, cadmium, hexavalent chromium, lead, lithium, and mercury. When these pits are breached, the coal ash can flow into the water supply and lead to serious environmental and public health consequences, including increased risk of cancer, learning disabilities, neurological disorders, birth defects, reproductive failure, asthma, and other illnesses.

Duke Energy, the main power provider for that region, maintains roughly 31 coal basins containing 111 million tons of coal ash. Following the drenching rains from Hurricane Florence, one of these pits at the L.V. Sutton Power Station (a former coal-fired power plant converted to natural gas in 2013) in Wilmington was breached. This pit spilled more than 2,000 cubic yards of ash into the Cape Fear River. Another three coal ash pits at the H.G. Lee Power Plant in Goldsboro were flooded when the Neuse River overflowed.

Duke Energy is in the process of excavating millions of tons of ash from the old waste pits at the L.V. Sutton and H.F. Lee sites and moving it to safer, lined landfills constructed nearby, although under North Carolina’s coal ash management law, they have until 2028 to complete these moves.

This is not the first time that Duke Energy will have to face the consequences of a major coal ash spill. In 2014, a power plant in the northwestern part of the state spilled more than 80,000 tons of coal ash into the Dan River and other connected waterways. The company pleaded guilty to criminal violations of the Clean Water Act going all the way back to 2010 and was ordered to pay USD 102 million in fines and cleanup costs. Since that time, Duke Energy has spent more than half a billion dollars to clean up coal ash stored at their facilities, but thanks to authorization from the state’s utility regulatory board, it has only had to bear 10% of the costs—passing almost 90% of the cost on to its customers.

Thus in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence, the people of southeastern North Carolina will be left to clean up the environmental disaster. Unless preventive action is legally mandated, we will be writing a similar blog post the next time a hurricane inundates the Carolina coastline.

Read my blog “Natech and the Liability Implications from Natural Catastrophes”