This year’s strong El Niño brings an elevated level of excitement to our seasoned AIR meteorologists, flood experts, and thunderstorm gurus whose greatest passions are found in the world of weather phenomena. Perhaps surprising to some, however, is the fact that those inclined to studying infectious diseases have a similar interest in the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Instead of monitoring alerts of abnormal weather events, however, we keep watch for atypical disease outbreaks.

Climate and Infectious Disease

Climate has a strong influence on infectious disease patterns. Temperature fluctuations can impact animal densities and habitat ranges, including those that carry and spread infectious diseases. Mosquito-borne illnesses provide evidence for this disease-weather link.

Members of the Aedes genus of mosquitoes are known to spread many infectious diseases, such as chikungunya, dengue, yellow fever, and Zika. They are also known to thrive in the mild to warm temperatures and plentiful rainfall that coincide with El Niño episodes.

Following one of the strongest recorded El Niño seasons, the largest yellow fever outbreak in the United States took place in 1878 and resulted in 20,000 deaths in the Mississippi River Valley. Dengue outbreaks in tropical regions are also well correlated with ENSO. With the strong El Niño season of 2015-2016, concerns mount about the subsequent possibility of communicable diseases spread.

Zika Virus

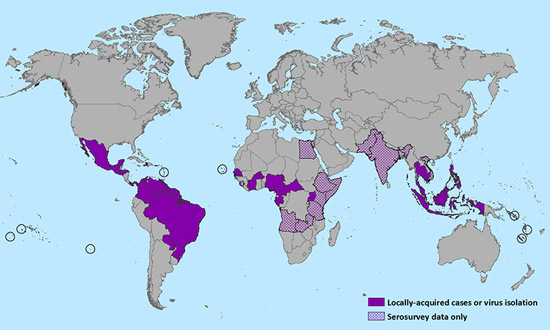

Zika virus garnered attention in late 2015, early 2016 when reports began streaming in from many countries in Central and South America. It’s been suggested that the mosquito population boom related to El Niño has exacerbated the large and rapid spread. People infected with Zika virus most often develop no symptoms at all; about one in five infections results in mild symptoms similar to the flu.

The current outbreak has brought to light a potential link between Zika infection and microcephaly, although a causal relationship has not yet been determined. Instances of Zika in regions outside of those where Aedes aegypti mosquitos―those thought to carry Zika―are native have been mostly related with recent travel to areas of active transmission. Instances of sexual transmission to someone without a travel history have been reported, most recently in Texas. Blood transfusions have also been reported to transmit Zika.

Zika in the U.S.

Cases of Zika virus in the U.S. have been associated with recent travel to areas with active transmission. Parts of the U.S. are home to the mosquitos capable of spreading Zika, thus there is some risk of local transmission in those states.

Many experts say a large Zika outbreak in the U.S. is unlikely for several reasons. These include the local infrastructure in place to control mosquitos, the common use of air-conditioners and screened windows to cool homes and keep mosquitos out, and that the species most capable of spreading Zika virus is only found in the warmer, southern parts of the country. The U.S. also has a historical record of eluding similar diseases. Only a small number of Chikungunya and Dengue cases have been reported in the U.S., despite widespread outbreaks in Central and South America.

Still, others say that Zika has a good chance of spreading in the U.S. due to elevated temperatures accelerating mosquito biology―including reproduction and feeding―and enabling faster virus replication. Andy Monaghan, a scientist who works on public health impacts of climate change at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, even predicted the northward migration of Aedes aegypti in a paper earlier this year.

Always Learning

As weather patterns change, so will the patterns of communicable diseases. The unusual weather experienced during El Niño gives us insight into the potential changes we may see in infectious disease distribution as our climate changes. While it’s too early to know exactly how climate change will impact the ongoing Zika outbreak, more will be learned as the event unfolds and historical outbreaks are related to unusual weather patterns.

* Currently, AIR does not model the Zika virus, although staff are monitoring the situation.