Note on the December 2013 Floods in Brazil

Feb 21, 2014

Editor's Note: Late last year, three southeastern states in Brazil suffered their worst flooding in decades. This article describes many of perspectives that can be used to understand the severity of a flood event and future tools to manage flood risk in Brazil.

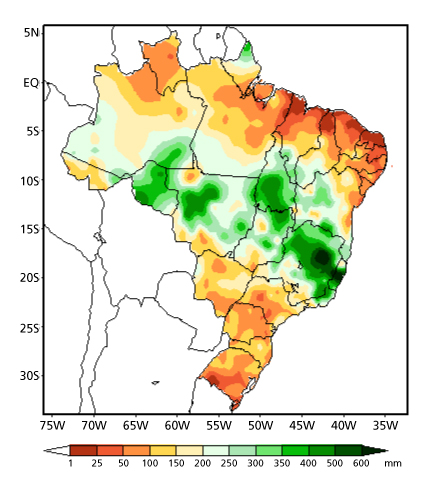

In December 2013, three states in southeast Brazil—Espírito Santo, Bahia, and Minas Gerais—endured weeks of torrential, record-setting downpours. Dozens of cities declared states of emergency, and by the end of the month, devastating flash floods and landslides had killed 45 people and left 70,000 homeless. The cost of infrastructure repairs in Espírito Santo alone is expected to reach BRL 540 million (USD 227 million).

The flooding was widely reported as the worst to hit the region in 90 years. Certainly many cities in the affected region experienced historic amounts of precipitation. For example, from December 1-27, the city of Aimorés in Minas Gerais received over 850 mm of rain, more than twice their previous record monthly rainfall, and the city of Capelinha, also in Minas Gerais, received just over twice their previous record monthly rainfall.

Rainfall accumulation, however, is not the sole indicator of flood intensity. While heavy precipitation is a necessary condition for river flooding, a multitude of other factors—including pre-existing soil moisture levels and river heights, and the presence of flood defenses—affect the severity of a flood. Thus, record-setting precipitation does not necessarily translate to record-setting flooding, and calling a flood a "1 in 100 year" event can mean several different things. Hydrologists and flood engineers examine several other measures, including but not limited to: water height (height measured from the bottom of the body of water), river flow, flood footprint, and inundation depth (height of water in flooded area).

For last December's event, river gauge data suggest that the severity of the flood event is not as extraordinary as the precipitation amounts would suggest. For example, the observed peak flow of the Rio Doce in Colatina for the December 2013 event was 962 m3/s. This level has been achieved or exceeded several times in recent decades, suggesting an annual probability of occurrence significantly higher than 1%. Risk managers can also look at the severity of a flood event from an insured loss or economic loss perspective (keeping in mind that exposure growth and inflation need to be considered when comparing a recent loss to those of past historical events).

Because of Brazil's continued economic development and expanding middle class, the insurance sector continues to grow; as a result, flood losses are an increasing concern for risk managers. Like any other natural catastrophe, flood risk is best managed with a probabilistic model that can consider the complete range of potential adverse events. Building fully probabilistic inland flood models, however, is computationally resourceful and can take many years. They also require extremely high-resolution and high-quality data on elevation and hydrology—data that may simply not be available for an individual country.

While there can be no substitute for the value of a detailed probabilistic model, AIR is currently developing alternative, yet scientifically rigorous tools for flood risk identification and accumulation management. The first of AIR's flood hazard maps will be released this summer for Thailand and China, and maps for key flood-prone regions for Brazil are currently under development.

The maps will be available as a geospatial layer in AIR's Touchstone® modeling platform and will display the extent of the floodplain associated with flow rates at the 1%, 0.4%, and 0.2% annual exceedance probabilities (100-, 250-, and 500-year return periods). Companies can use them to assess how much of their accumulations of replacement value, risk count, and exposed limits fall within the floodplains. User-defined damage ratios can also be applied.

As insurance penetration expands around the world, so too does exposure to catastrophe losses. To meet growing needs, AIR is committed to providing innovative tools for currently non-modeled perils and regions to help the insurance industry manage accumulations and make better underwriting decisions.

1 In 2010 dollars.

2 http://www.preventionweb.net/files/20634_floodriskinbrazil1.pdf

By: Mark Szretter

By: Mark Szretter