Tornadoes can happen at any time in the U.S., but generally most occur between March and June. Ordinarily, tornadoes are least likely to occur in winter, but tornadic activity in 2017 got off to a rapid start. Based on storm reports collected by the National Weather Service, there have been 207 reported tornadoes in January and February.

Southern Tornadoes

A large portion of these occurred in the January 21–23 southeastern outbreak. The majority of these tornadoes were rated EF-1, a category that produces winds up to 110 mph. Three EF-3 tornadoes also occurred, generating winds up to 165 mph; one of these caused heavy damage to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, which had been hit by an EF-4 tornado in 2013, and another in Georgia had a track more than 70 miles long and heavily damaged the city of Albany.

In terms of the number of twisters, this was one of the largest winter severe thunderstorm outbreaks on record. The only instances on record with more are the 127 tornado outbreak that touched down across the Mississippi River Valley from January 21–23, 1999, and the February 2008 Super Tuesday outbreak (87 tornadoes) that devastated the Southern United States and the lower Ohio Valley during the primaries for the upcoming presidential election.

Winter Tornadoes

There were other significant tornado outbreaks this winter. On January 2 major damage occurred from tornadoes across Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. New Orleans experienced its strongest tornado on record (EF-3) as eastern areas of the city saw heavy damage on February 7. Another record was set in Massachusetts on February 25 when an EF-1 passed through the towns of Goshen and Conway; this was the first February tornado on record for the state. In addition, a February 28–March 1 outbreak produced tornadoes across much of the Midwest. This included the first EF-4 of the year, which traversed a 50-mile path through southern Missouri and Illinois.

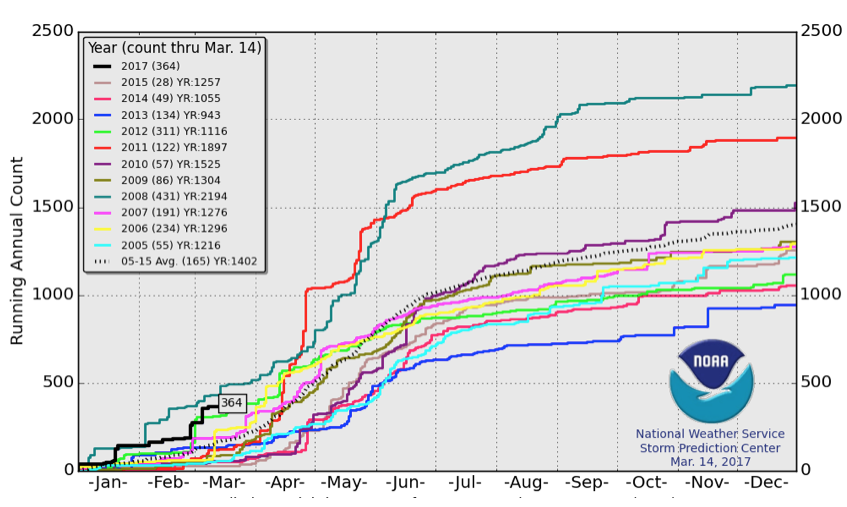

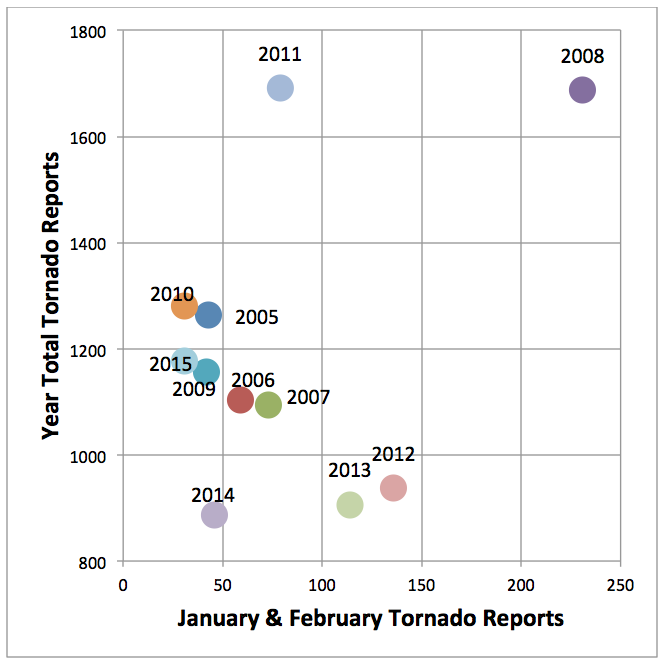

The total for the year is currently well ahead of average for this date based on the 2005–2015 record (Figure 2). The only recent year to start out faster was 2008, which included the Super Tuesday outbreak.

Tornadoes spawn from thunderstorms, which require warm, humid air as their source of energy—atmospheric ingredients absent during the winter for much of the country. The exception is the southeastern United States, where these conditions prevail more frequently in the cold season due to its proximity to the Gulf of Mexico. Supercells, types of thunderstorms that produce the vast majority of tornadoes, also require high vertical wind shear (i.e., an increase and turning of wind with height). This promotes storm longevity and rotation, making tornadogenesis (or the formation of a tornado) more likely. During winter the jet stream—a current of fast moving air at high altitudes—is usually positioned farther south, providing vertical wind shear to storms.

Tornado Forecasts

It would be helpful if the early season activity had predictive capability for the whole season, but unfortunately that is not the case. For example, 2011 started relatively quietly compared with the average, but ended up having the second-highest number of tornadoes in the last decade. There were also two outbreaks with the greatest number of tornadoes in history that year: the April Super Outbreak and the May outbreak, which included the Joplin tornado. Conversely, 2012 began very actively but ended up being one of the least active of recent years (Figure 3).

A general rule is that phenomena smaller in size and shorter in duration, such as tornadoes, are less predictable due to the chaotic nature of the atmosphere. The atmospheric environments in which tornadic thunderstorms develop are more predictable because of their larger scale. Currently these environments can be predicted several days ahead of time.

If environments could be linked to global-scale climate patterns such as El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), then seasonal prediction of tornadoes could become more reliable. This is an active area of research in the meteorological community. Perhaps in the near future there will be seasonal forecasts for severe thunderstorms and tornadoes, analogous to the predictions made for tropical cyclone activity.