Although Lassa fever is endemic to Nigeria, a recent outbreak of the disease there (with 110 deaths as of March 4, 2018) is the worst to date for the country, according to the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC).1

Lassa fever, named after the Nigerian city where the first case was diagnosed in 1969, is a hemorrhagic fever transmitted to humans by contact with urine or feces of the Mastomys natalensis rat. Human-to-human transmission is possible through blood, urine, feces, or other bodily secretions of an infected person—particularly in hospitals and healthcare facilities. Lassa fever is an acute viral illness with some symptoms similar to Ebola, but it is less contagious and less deadly, resulting in less major pandemic potential. This year’s outbreak had an estimated case fatality rate (CFR) of 20%, which is higher than normal (1%–15% among hospitalized patients).

Lassa fever is difficult to diagnose because only 20% of Lassa fever infections are symptomatic. Moreover, its symptoms are generic and similar to other diseases endemic to the region, such as malaria, typhoid, and influenza. In addition, the duration of the illness and its incubation period are long, ranging from one to three weeks, which provides an opportunity for the disease to spread unnoticed. There is no vaccine available for Lassa fever, and the only treatment available is an antiviral drug—Ribavirin—which has serious adverse effects and needs to be administered during the first week of infection, making it of limited utility in most cases.

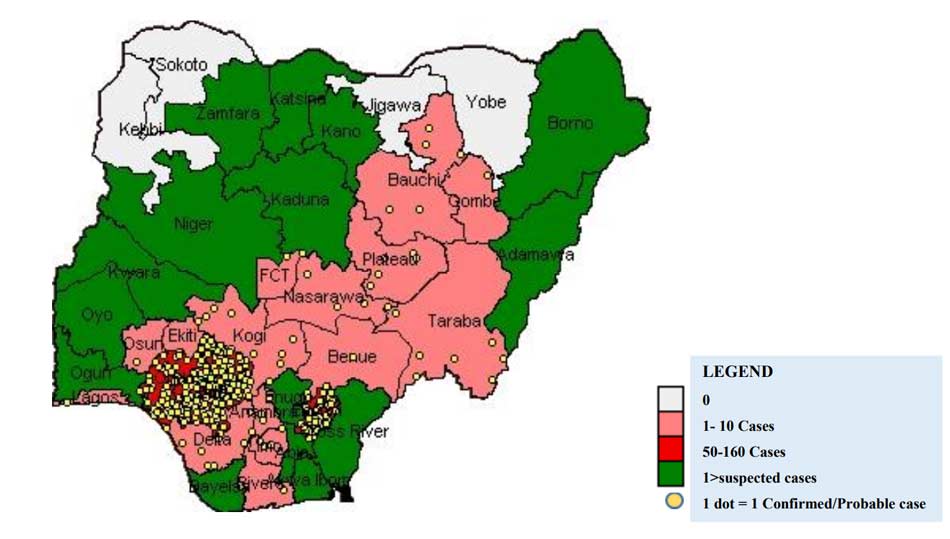

According to the NCDC, between January 1 and March 4 of this year there were 1,121 suspected cases with the largest number of cases concentrated in the southern states, including Edo, Ondo, and Ebonyi. Of these cases, 353 have been confirmed, 8 are probable, 723 are negative (not a case), and 37 are pending.

Currently, trained healthcare workers are managing the outbreak; however, the increasing number of cases might cause shortages of staff and protective equipment. With confirmed cases from different parts of country, the World Health Organization (WHO) is also warning of the possible risk of spread to neighboring countries.

Recent urbanization, population growth, expansion of agricultural land use, and the concomitant spread of Mastomys natalensis rodents all contribute to making this outbreak more severe than those in previous years. Isolation of affected patients, contact tracing, and good infection prevention measures can help to stop the outbreak. Fortunately, Nigeria has a strong and effective public health infrastructure, and experience with these types of outbreaks. Public health workers in Lagos were able to completely halt an outbreak of Ebola in 2014 using intense and rapid contact tracing, surveillance of potential contacts, and rapid isolation of all confirmed contacts.

Following the 2014 experience of Ebola, this year’s outbreak of Lassa fever is getting more attention from media and international organizations. Fortunately, this increased awareness is leading to more infectious disease experts being sent to the field, showing a fast response to the outbreak in an attempt to stop the disease from spreading to other countries in the region.