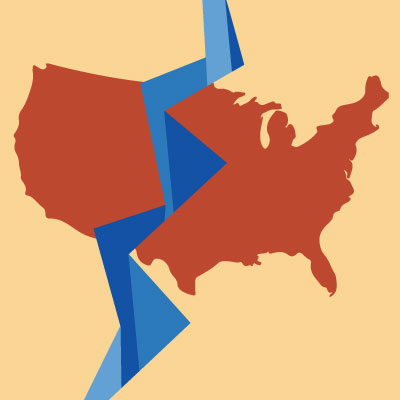

View animation (Requires Quicktime)

The first 3 hours of tsunami propagation after the 2004 earthquake(Source: USGS)

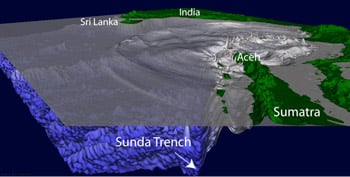

A decade ago, one of the deadliest natural disasters in history killed more than 230,000 people in 14 countries around the Indian Ocean and caused significant damage in five more. The magnitude 9.1-9.3 megathrust earthquake occurred 250 km south-south-east of Banda Aceh, Indonesia. It shifted the seabed violently by perhaps 10 m horizontally and up to 12 m vertically, rapidly displacing vast amounts of water and unleashing a tsunami of epic proportions.

Tsunami waves of 15-30 m hit the northwest coast of Aceh within minutes. The waves that wrapped around the tip of the island to strike the city of Banda Aceh about 20 minutes after the quake were about 10 m high, and the area's low elevation enabled them to penetrate far inland. Within about two miles of the shore, a third of the city-and a third of its population-disappeared. Other parts of the city, which had largely survived the earthquake, experienced severe damage from flooding.

Devastation near Banda Aceh following the December 26, 2004,tsunami (Source: U.S. Government)

The tsunami changed the island in many ways. Some coastal areas subsided 1-2 m and in others, land disappeared, eroded by waves that deposited debris far inland. Foreign aid has poured into the area, and in an almost exemplary reconstruction, 1,700 schools, nearly 1,000 government buildings, 36 airports and seaports, 3,700km of road and more than 140,000 houses had been built in Aceh by 2010. Banda Aceh now has things it never had before, like preschools and modern drains.

The imperative to focus on recovery ended three decades of fighting between the Indonesian government and the Acehnese independence movement. The economy and society have rebounded, but the tsunami marked many people and places. The tourists now returning to Banda Aceh can visit a Tsunami Museum and several of the vessels washed ashore. About a mile from the shore, 16 m high reinforced concrete tsunami towers punctuate the skyline. Each is designed to provide a safe refuge for 500 people, and has a flat roof that can be used as a helipad for evacuation.

The Tsunami Museum in Banda Aceh (Source: Si Gam, Wikimedia Commons)

The most important legacy of the tsunami however, is invisible.

The death toll around the Indian Ocean was so high largely because there was no warning, and no escape. The Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System, an intergovernmental project, was initiated in January 2005 in response to the disaster. Sensor data from 25 seismographic stations and 6 Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami (DART) buoys is transmitted to the U.S. Pacific Tsunami Warning Center in Hawaii and the Japan Meteorological Agency for processing, and alerts are forwarded to threatened countries.

The system became operational in 2006. When a magnitude 8.4 earthquake struck Banda Aceh in 2012, power failures delayed the sounding of some of the warning sirens-but the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal were alerted within 8 minutes of the quake. No one can stop a tsunami, but advance warning and better knowledge about how to respond to a tsunami threat can save countless lives when the next big one strikes.

For a more in-depth look at how earthquake and tsunami risk has changed in the last ten years, please read this AIR Currents article.